Three looks

In Jasper Johns’s “Painting Bitten by a Man,” the artist has bitten a hunk out of his painting, leaving behind teeth marks. The action of the bite transforms into an image to be seen, an image that relates to nothing else on the field of gray encaustic. The bite conjures the presence of the artist at work and a flash of spleen. The gesture of the bite keeps receding back into its intrinsic muteness, suggesting the frustration of a desire to communicate verbally. At the same time, the plain speech of the title stands in stark contrast to the enigmatic bite mark; the temptations of legibility and illegibility animate one another. In a sketchbook, Johns writes, “‘Looking’ is and is not ‘eating’ and ‘being eaten.’”[1] Looking may (or may not) approximate eating, biting, marking, writing; perhaps what is also pictured here is the viewer’s gaze (sexual, temporal, avid) expiated by realization. I’ve always viewed this painting as a kind of aggrieved self-portrait because of what is pictured: the bite literalizing the self’s effort to be as real as the mark it leaves on a representational plane.

Another kind of distressed self-portrait: in 1953, Robert Rauschenberg made “Erased de Kooning Drawing.” Variously interpreted as a patricide, a collaboration, an homage, an essay on draftsmanship, a beau geste, it is also an approach to looking, a critique on a purely optical, disinterested way of viewing art. Rauschenberg is said to have begun the project by erasing his own drawings, but he found that for the final work to have any traction, he needed to start with another significant artist’s work; he sought to suppress something external to his own practice to summon something new. In erasing de Kooning’s work, he makes a strong equivalence between that famous artist’s act of drawing and his own act of erasure. This erasing-as-drawing gets at looking, or rather a kind of representation of looking, negatively. On view are just the faintest traces of crayon and ink, yet Rauschenberg once insisted, “A canvas is never empty.”[2] The almost invisible quality of the picture takes us from a purely optical moment to a mode of address; the artist captures our awareness of the conditions of our perception (active, contingent, coming upon absence) in that near-blank return “stare” of the canvas. The ghostly presence of the disappeared drawing and the telltale marks of its erasure even suggest that we are looking at representation coming to consciousness of itself.

John Ashbery’s poem “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror”[3] is in one vein, a lyric consideration of looking’s strangeness. In the poem, looking is understood as temporal, corporeal, and intimately tied up in the structure of subjectivity. The poem explores how this sort of looking in self-portraiture is pictured as the very form of representation; self-portraiture vividly illustrates how immediacy and self-evidence come to lack any self-sufficiency the moment representing starts. The self-portrait shows “both” the self and the self’s gaze or cast of mind turning back on the self; it renders the seeing visible, regrouped in time and space. Looking is framed and intensified on multiple levels in this poem: Parmigianino and the mirror-portrait, Ashbery’s ekphrastic poem, the self-reflection and self-portrayal of both artists, and not least, the reader’s complicit positioning. The opening “As” of the poem casually posits the reader’s implicit self-projection into the position from which the painting (and poem) was made:

As Parmigianino did it, the right hand

Bigger than the head, thrust at the viewer

And swerving easily away, as though to protect

What it advertises.

The distortion of looking gets figured in the mirror’s reflection of head and hand; bigger than the head, the hand approaches and recedes from the viewer. The hand’s possible dramatic implications, its protective guise or its “reflex / To hide something,” get reinterpreted within the circumstances of the painter’s medium: “There is no way / To build it flat like a section of a wall: / It must join the segment of a circle.” And so the convexity returns the hand towards the body “of which it seems / So unlikely a part.” In the mirror, the hand does not make sense in terms of scale. It acts as a metaphor for both sensory data (the strange reflection of the hand in the convex surface) and the experience and interpretation of that data (all the implications of “handling”). The mirror’s distortion, whether unsystematic or expressive, paradoxically draws the hand back towards a greater materiality by indicating touch and literal paint handling. It also indexes the self-consciousness of the moment, since the hand wants to break out of the system of representation — “One would like to stick one’s hand / Out of the globe” — but it cannot really exist outside that system and still be seen.

The hand is not the only thing that wants to escape the portrait; that hand points to, or in the poem’s language, “shore[s] up” that mysterious face of the painter. And within the face appear the eyes, which, in the custom of self-portraiture, signal the self’s inwardness: “The soul establishes itself. / But how far can it swim out through the eyes / … unable to advance much farther / Than your look as it intercepts the picture.” The soul, that consciousness of individuality on the one hand, or an intimation of wholeness and boundlessness on the other, is determined by the onlooker’s attention, rather than characteristics inherent to itself. The adage of the eyes as windows to the soul, the standard instrument of interiorization, is found to be impoverished:

But there is in that gaze a combination

Of tenderness, amusement and regret, so powerful

In its restraint that one cannot look for long.

The secret is too plain. The pity of it smarts,

Makes hot tears spurt: that the soul is not a soul,

Has no secret, is small, and it fits

Its hollow perfectly: its room our moment of attention.

Instead of depth and metaphysical mystery, we are left with an image of looking. The soul “has no secret.” The understanding that a soul has of itself is a kind of seeing, but it’s the kind of seeing demonstrated in Johns or Rauschenberg’s work: seeing pictured as robbed of its self-evidence, and yet shown to have other powers.

This sort of seeing might open up other ways of contemplating what it could mean to have or be a self. This re-presented, pictured self-consciousness (as hand, as Parmigianino’s gaze) can act as supplement to an idealized, totalizing vision (the one exempt from or exterior to the circuit of representation): “This otherness, this / ‘Not-being-us’ is all there is to look at / In the mirror.” These representations, or aesthetic forms, are not transparent, but they have a different ambition, they motion towards the artist’s desires and dreams:

The forms retain a strong measure of ideal beauty

As they forage in secret on our idea of distortion.

Why be unhappy with this arrangement, since

Dreams prolong us as they are absorbed?

Something like living occurs, a movement

Out of the dream into its codification.

The codification of form (“second-hand knowledge” he calls it later in the poem) is necessary to look back on the dreaming; the movement between dreams and forms is characterized as living itself. This sort of looking, involving loss and diffusion, replaces soul with all its force and enigma.

I like to read Ashbery’s poems alongside the work of Johns and Rauschenberg in part due to the ways in which all three artists investigate the literal aspects of their medium’s processes and enlist them to deploy a generative self-reflexiveness in their works. I’m interested in how the artists’ skepticisms become a sustaining part of picturing at all. The nature of self-reflexiveness, and its attendant characteristics of skepticism, irony, wit, coolness of tone, are, in their works, both conserved and yet more than inclusive of the forces often taken as their foils: ardor, advocacy, confession, material lushness. For Ashbery, the example of painting and painterly experimentation acts as an expansive and apposite setting for contemporary language to explore self, representation, interiority, legibility, agency. Casting self-consciousness and its abstractions in terms of representation saves them from a naïve transparency and gives the reflective topography a kind of concreteness in imaginative reach. It’s also where the seductive aspect of his (and Johns and Rauschenberg’s) self-portraits often comes into play. In the self-portrait where one confronts seeing’s strangenesses — its guises and aggressions, distortions, erasures, feints, manipulations, and second thoughts — one may more viscerally encounter the possibility that such components are constitutive of the mystery that can be created in no other way.

1. Jasper Johns, “Sketchbook Notes,” quoted in John Yau’s “The Mind and the Body of the Dreamer,” in Uncontrollable Beauty, ed. Bill Beckley with David Shapiro (New York: Allworth Press, 1998), 298.

2. Leo Steinberg, Encounters with Rauschenberg (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 10.

3. John Ashbery, Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror (New York: Penguin Books, 1975).

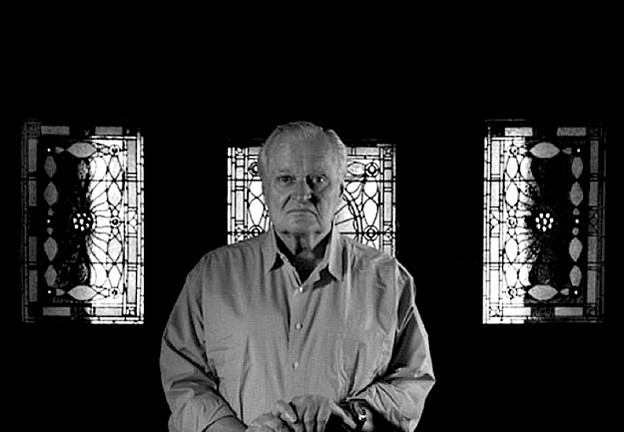

John Ashbery and the arts

Edited byThomas Devaney Marcella Durand