Three future dances, or the dance feministic

1.

We are drawn together to march but because we are so many, we cannot march. We can only shuffle off balance, lean, wind our way, press or fall against one another, allow ourselves to be moved, give up our bodies to the swarm. And so we find we are not militant but in motion, a motion we can’t master. The speakers we can hardly hear, on a stage we cannot see, are saying what we expect but still need them to say: that we are outraged; that we will unite; that we will resist. The elected president is a sexual molester and beauty pageant aficionado. He’s quite possibly a rapist. He’s certainly a pawn of the global fascistic far right. It is day one, but we know what is coming, what he and they have in store for us. Their priorities have already been made clear. Promilitary, propolice, pro-oil and procoal, anti-immigration, antipoor, antigay, antiblack, anti-Muslim, antiunion, antiplanet, and antiwoman. None of this is new. All of these “positions,” or more, strategies for greater wealth, all of this criminal power, have been with us, whether avowed or not, whether acknowledged, by us, or not, for our entire lives, as ordinary as the grass we trample in our swarm.

But here we are, disgusting and desired, shamed and shaming. Here we are, groped and raped, self-hating and self-loving. Here we are, infighting and frightened. Here we are with our reproductive bodies, our pre or post-reproductive bodies, our nonreproductive bodies. Here we are with breasts lopped off or breasts added or breasts altered or breasts just beginning or no breasts. Here we are with our mouths open and our vaginas, if we have them, open too. Here we are, bleeding from wherever. Here we are with all of our (self) disgust and all of our shared and unshared refusals to be groped, raped, or policed, even as we are, and have always been groped, raped, and policed in uneven doses.

We are, in the way of a viscous organ, pinkly pulsing. Whether we are kids, grown, or old, whether we are called a color or call ourselves one or are called or call ourselves white, whatever gender we claim this day or any other day, we are, here there and everywhere in our un-marching march, our swarming shuffle, women, made so by our desire to not be groped, raped, or policed.

2.

On the day after the march, we spent the night at Laynie’s house where I first opened what she had compiled. Among the poems and artworks I pored over and so much needed, I found the surprise of Mette’s Moestrup’s “She’s a Show” — an absurdist response to the global situation we now encountered, or a situationist encounter with the global absurd, a counter-absurdity for the resituated we, a spawning site, a glowing romp, a dance and a song.

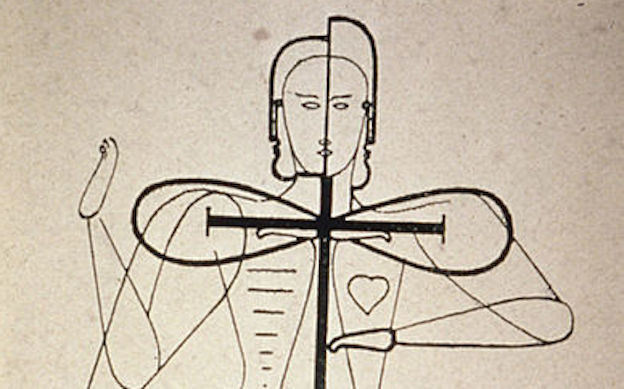

Mette’s dance (text by Moestrup, music by Miriam Karpantscho, video by Kajsa Gullberg) delivers a goofy and dead-serious critique of whiteness, patriarchy, corporate culture, and the commodification of the body that all of these ideologies enforce. “The white uniforms / The white uniforms in the metal lockers / They are waiting for an anonymous body / They are waiting for my body,” go the lyrics, while the dancers pound out their refusal: “I work physically for money in my uniform,” “and dream of a classless intelligencia.” The “dance feministic,” as the song calls it, is a defiantly happy shimmy and thrust and a lipsticked grin that won’t give itself away. On the day after the day after the inauguration, this is the protest I most need, the dance of the future spilling the anonymous body out of its too-short white uniform, the body that would otherwise only work for the money, on and on and on.

3.

One evening in Omaha six months after the election and after a difficult day in a one-hundred-year-old archive in which genocidal whiteness expresses itself through the voice of my great-grandfather as a decade-long passion for eugenics — which was nothing other than an urgent wish for racial purity, a gripping fear that as women (of any race) birthed babies who were not white, or as any woman with any disability, mental, physical, or circumstantial, gave birth at all, white power would be slowly but definitively decimated — after encountering, through this ancestral voice, a protracted and variously expressed desire for stronger legal barriers against otherness, which was also an absolutely transparent need to control, through surgical and other means, the sexual/reproductive bodies of women — we found another dance.

The streets of Omaha are wide and empty; the buildings look shut even when they’re not. Traffic is light and in midsummer all the car windows are up. The city feels lonely to drive through. And then we turned a corner and came upon a crowd — a concert on a grassy hill, the audience gathering or already in their lawn chairs, coolers by their feet. We parked the car and walked into the grass, and when the band began (Hector Rosado y Su Orquesta Hache, from Philadelphia) we, and everyone else, started dancing.

There on the dance floor with the black, brown, white, old, young, male, female, abled and disabled bodies, we entered the future. On the outdoor dance floor where race-suicide is a practice of giving over the whole notion that we are anyone to begin with, where the body finds itself no longer a speaking thing, no longer a force that projects, but instead and only a response, we move illogically, not to assert superiority or even particularity but instead to be with. A white woman in her fifties in a tangerine pixie dances with a black man in a little grey cap. A brown boy, awkward and about thirteen, dances with a white girl whose ponytail syncopates her hip swing. A blind man with hair to his waist dances with a seeing woman dressed all in purple. Someone in a tight dress and heels catches my friend’s eye, grabs her by the wrist and gets her into a samba. The babies bounce and the aged, even those who never leave their lawn chairs, dance with tapping feet, and with their eyes. Dear great-grandfather, I said to the sky, look now at us suicidal dancers and see how all your fears came true, how all your fears were phantoms.

To dance or swarm, to find that “electricity erratically anoints you” (Moyna Pam Dick) in the presence of the bodies of others you do not yet know, to be among friends in a future dance floor of strangers, is to “to start your shape all over again” (Rusty Morrison), or to enter the nonstate of being in common. This is the “um bilical ’tween” (Julie Patton), a slipping gesture, a slide to the side of the forms of power that seek to contain us in the “tragedy of our atomization” (Anne Boyer), in our uniforms that never fit. We know that such momentary escapes do not easily translate into the daily, though they might linger on in the sense-memory of the body. We know we don’t and can’t know what any of the other dancers or marchers or swarmers go home to. The dance is not the day, but it is the protest, it is “the throbbing abdomen of the clearing, its verdant pulse” (Oana Avasilichioaei). To close the books, exit the library, and travel to the future is to find that the future is a beat, “hope still streaming in” (Anne Waldman), and it moves us and makes us move.

This is the dance feministic.

Edited by Laynie Browne