In moveme/braces

Erica Baum's 'Dog Ear'

In 2008 I had the pleasure of working with photographer Erica Baum on an exhibition project through KWH Art, the gallery I then directed at the Kelly Writers House. In keeping with the tenor of the space and its co-function as a reading venue, I was curatorially inclined toward work with affinities to language and concrete poetry. Baum had just completed a new series — probably my favorite to date — entitled Roll Playing, comprising high-contrast, perfectly square photographic crops of player piano rolls. On the left of each image runs a graphic salvo of dashes, flecks, and various other notations, translated from voids coded for the instrument’s pneumatic mechanism (as a sort of continuous punchcard) to positive black marks in the photograph. On the right, a stuttering excerpt of often folksy, sentimental song lyrics is rendered in a sterile, stenciled font flowing up the page in tempo with the musical data opposite. In close collaboration with the artist, I curated a selection from this series into the exhibition Word Each to Cling I, which was supplemented by a small publication and opening programming.

By then Baum had already been repurposing text-based archival materials such as card catalogues and indexes for some time. Her most recent project, Dog Ear, follows in this vein, imaging pages from unidentified paperback books. Each photograph is formally consistent: a diagonal fold from upper right to lower left corner peels back the page to reveal both the text on its reverse side and that of the page underneath. This simple maneuver, conventionally functioning to mark a reader’s place, is under Baum’s lens a complex syncopation; a new text sutured from discontinuous lines torques prose toward prosody at a crude right angle.

Geometrically speaking, the new lay of the language — confounding comings and goings as it seeps from two directions into an eliding cleft — is a familiar but intriguing ravel. In beginning to grapple with the disjointed poems Baum has in effect created (and she has openly identified her text work with poetry in the past), I found a constructive byway in transcription. Hazarding to reclaim some left-right, top-bottom continuity, rewriting her lines pulls them into another particular formal disposition: right triangles, tapering from the first and longest composite line down to the murmur of the final fragment, nearly completely obscured by the fold.

Serrated edges and typographic detritus (dismembered serifs and ascenders) are part and parcel of Baum’s images, but taking corrective liberties in their reading is by and large inevitable. Subjective inferences and skips (burrows and overpasses, if you will) make Baum’s fragmentations dynamic, opening an imaginary space where the conditions of viewing are always vacillating with those of reading.

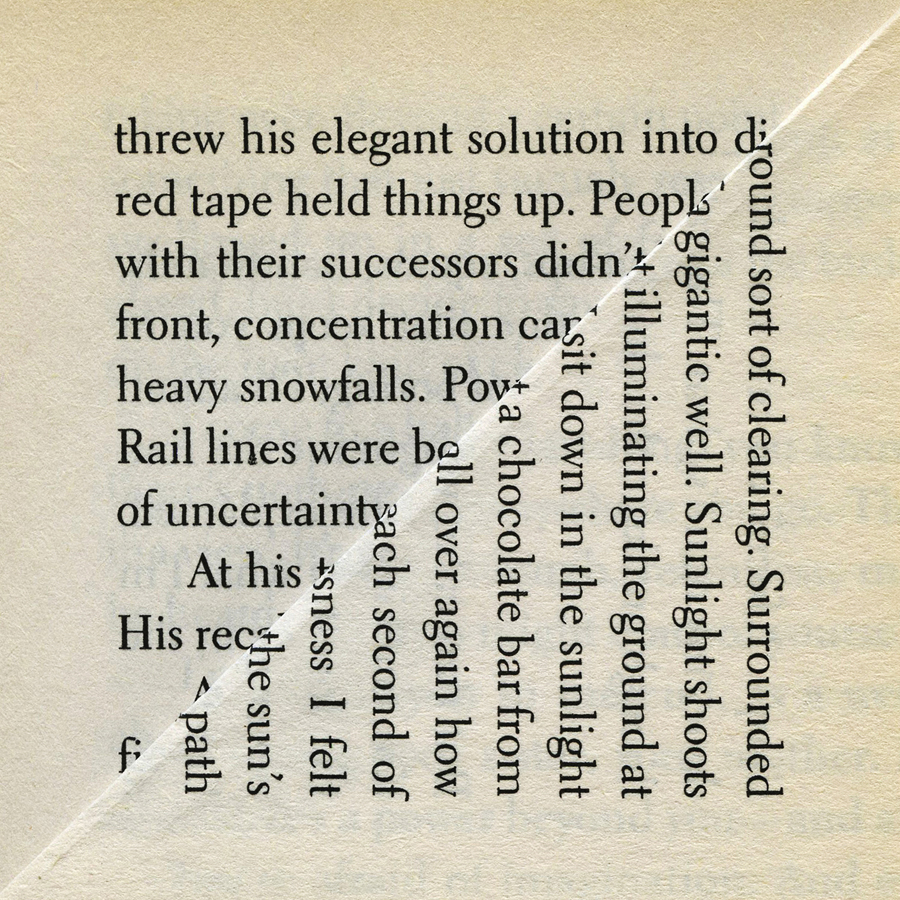

threw his elegant solution into round sort of clearing. Surrounded

red tape held things up. People gigantic well. Sunlight shoots

with their successors didn’t illuminating the ground at

front, concentration can sit down in the sunlight

heavy snowfalls. Pow a chocolate bar from

Rail lines were bell over again how

of uncertainty each second of

At his [ ]sness I felt

His rec[ ] the sun’s

path

Restoring the shards is especially seductive toward the end of this piece, as quivering details of a landscape skirt some relic of personal intimacy, ebbing and faulted. At his [tenuou]sness I felt [ ]? His rec[alling] the sun’s / path? The fringe’s imprecision pushes speculative readings under Baum’s artifice, inviting a new interpolated narrative in lieu of fidelity to the source. Nevertheless the elision remains active in tantalizing us to de-flatten it, to pull the single plane of the image back into codex form, to know and claim the vestigial lines that continue under the surface.

Here the impeded voice itself consents to the pleat:

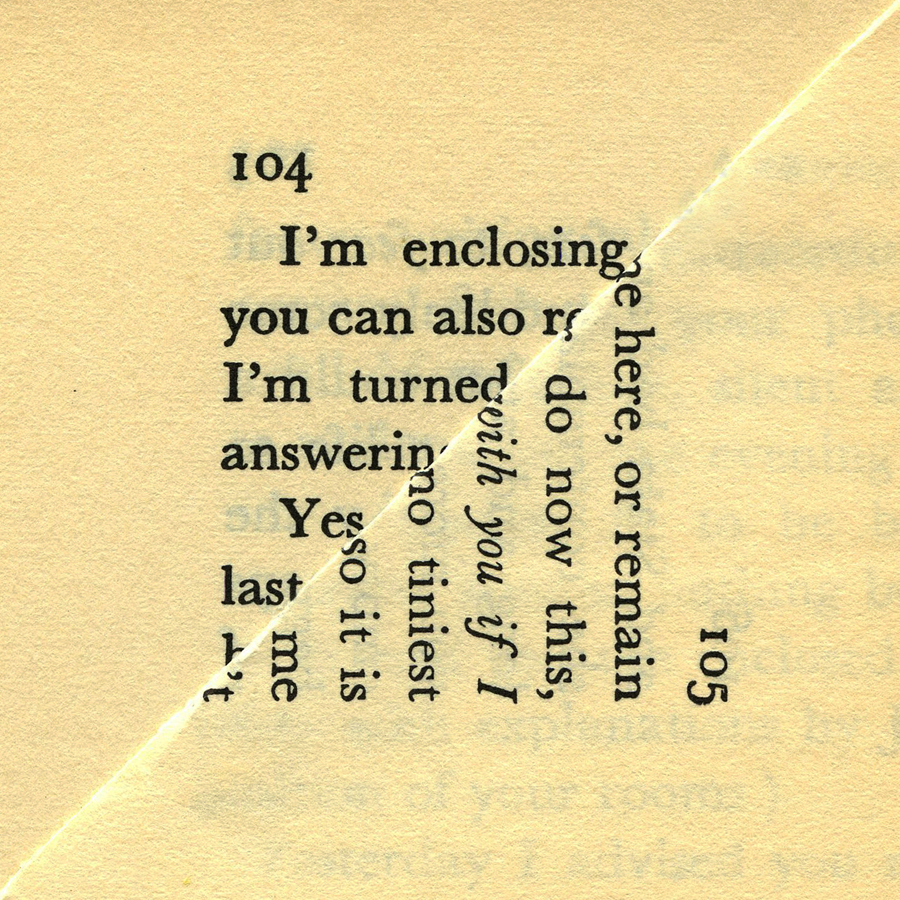

I’m enclosing me here, or remain

you can also do now this,

I’m turned with you if I

answering no tiniest

Yes so it is

last me

The first me careens into (or rather, out of) the crease, tangibly demonstrating its synthetic context, then adjusts its bearings to an alternative here, on the face of the page we see. But the visibility (read: legibility) of this location is entirely contingent on Baum’s composition; here would be recto, that is, concealed, if not for her distortion. A downward directive (do now this) literally overrides what else we can also r[ead] beneath, and again the text follows itself in turning with you as your eyes scan the line. Yes, so it is. The last me recurs as literally the final intact morpheme, reminding us that here deixis is a sweeping condition; truncated lines withhold antecedents and reconfigure the associative fields of their respective pages. I, me, you, now, this, and it operate in riddled circuits dependent on Baum’s formal intervention (which, however compelling, is notably minimal, and largely based on a refined practice of appropriation).

Indeed, one of the series’ most successful gambits is its subtle perversion of the movements coded in seeing and apprehending language; Baum’s pieces double-register as both continuous texts and collage fragments in a way that demands conscious reconsideration of our activities of viewing them. Because each of the two triangular excerpts so emphatically signify the context of a printed book, a first reading may struggle to maintain their respective autonomies, and yet the diagonal break inevitably forces false steps. At the end of each line fragment we must either jump the gap and turn the corner or, in a conservative bilateral reading, repeatedly abandon each line at its severed stump to rejoin at the left margin (or vice-versa). Either trajectory ends at the lower left corner, having agilely subverted our reading backward even as we scanned left to right.

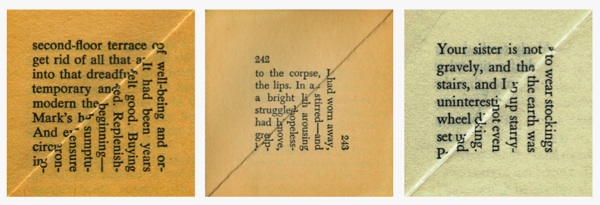

second-floor terrace of well-being and or-

get rid of all that It had been years

into that dreadful felt good. Buying

temporary and sed. Replenish-

modern the beginning —

Mark’s sumptu-

And ensure

circuaron

in o-

to the corpse, I had worn away

the lips. In a stirred — and

a bright arousing

struggled hopeless-

had move,

grelp-

Your sister is not to wear stockings

gravely, and the the earth was

stairs, and I up starry-

uninterest not even

wheel king.

set und

Most often paucities assert themselves at both fold and enjambments, but at times joints flex gracefully: second-floor terrace / of well-being and or- / get rid of all that / It had been years / into that dreadful / felt good. Baum’s most fluent choreography occurs in lines with multivalent midsections, engendering a streamlined turn of phrase: consider, for instance, get rid of all that [i]t had or It had been years — the hinge it had can operate either in an adjective clause modifying all or as part of the subject-predicate It had been. Though the graft is visibly exposed by the spare a and capitalized I, the line morphs through its reading; the text is at once rent and teeming at the tears. (Dreadful feels good on the terrace of well-being.) Occasionally the effect produces an even more sustained lyric drift: to the corpse, I / had worn away, / the lips. In a / stirred — and / a bright / arousing / struggled / hopeless- / had / move, or, Your sister is not to wear stockings / gravely, and the the earth was / stairs, and I up starry-. In the latter, only the stuttered article in the second line and the syntactic glitch of I up starry admit the game.

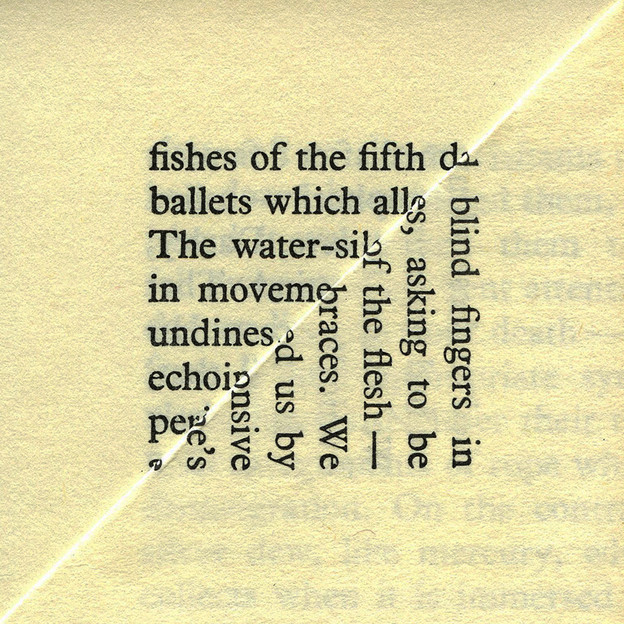

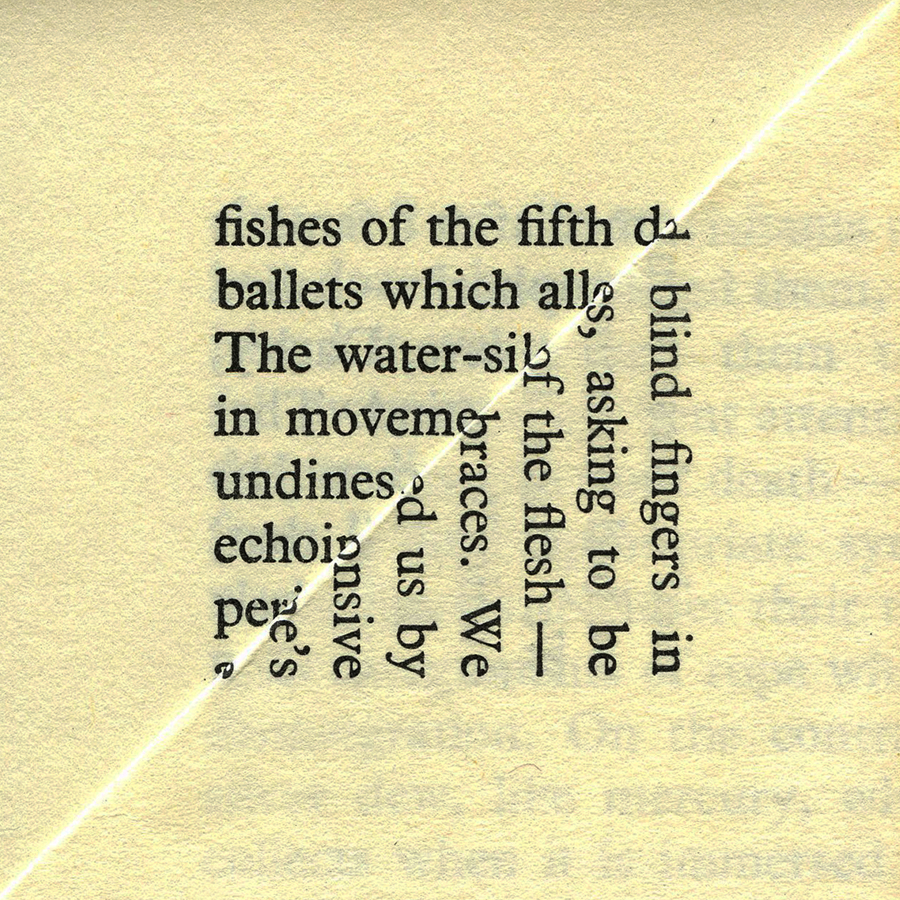

fishes of the fifth blind fingers in

ballets which alles, asking to be

The water-sil of the flesh —

in moveme braces. We

undines us by

echoionsive

pere’s

From a given angle, Baum’s compositions outfit each amputated line with an aleatory prosthesis, a new limb hanging limp from the socket. The water-sil of the flesh — / in moveme[nt] braces. Poised awry in a chevronic stagger, each line of the text undulates and jerks in a lissome, still stilted, pas de deux.

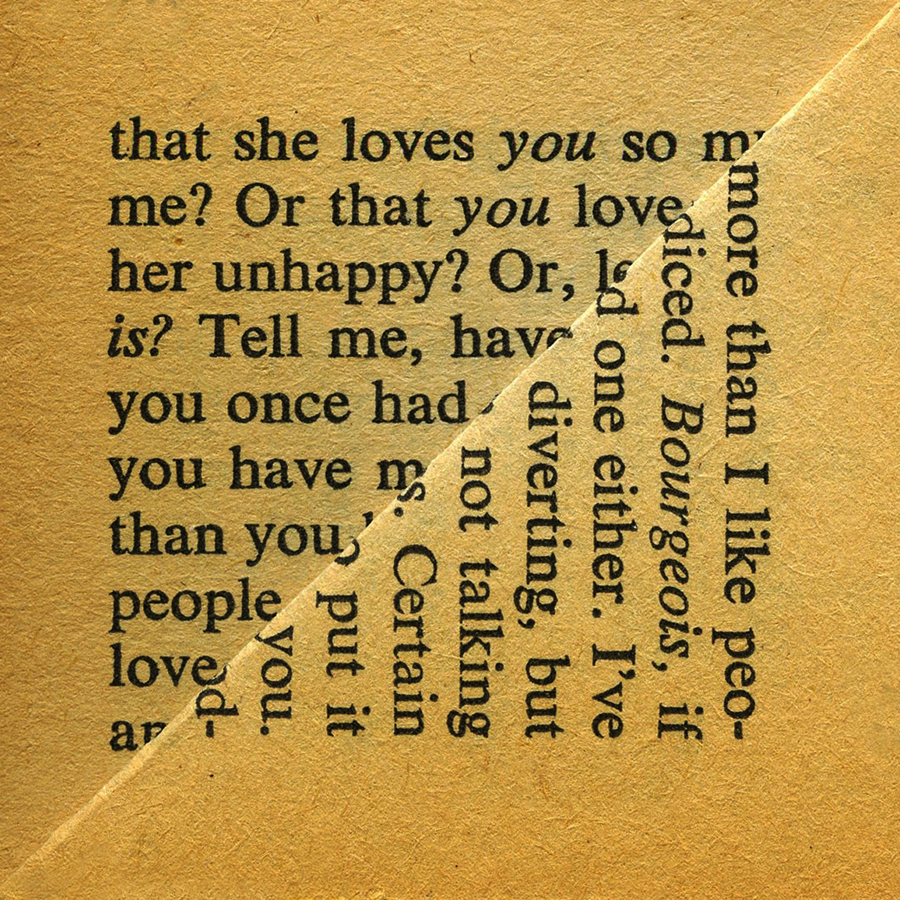

that she loves you so more than I like peo-

me? Or that you love diced. Bourgeois, if

her unhappy? Or, one either. I’ve

is? Tell me, have diverting, but

you once had not talking

you have Certain

than you put it

people you

loved-

a

Dialogic subtexts pervade the series, but in this example especially, with its apprehensive twitches and dislocated pronouns. Tenterhooks strain the text internally and along its periphery, from the initial if/or disquietude through to the modal brink: Tell me, have / diverting, but betrays an abridged parley (directive and detour, plea and shirk) or, in the seamless transcript, a schizoid self-defeat — even an exhortation for understanding is derailed by agitation and doubt. In two voices you once had / not talking might be nostalgia met with withdrawal, or univocally, a protest against the communication impasse (you were once silent; now speak!). Then you have / Certain seems another strain to know the other now (or here), verging on but (literally) barred from that Certainty that you must possess. Is it you there, on the other side? Are you fixed or repeatedly oscillating with me? What is intertext and what is internal — where is our relation based? With this Baum’s text continually contends both concretely and semantically. At last, love tips into the past by way of the fold, if protested by the hyphen’s forward jut — love / diced.

***

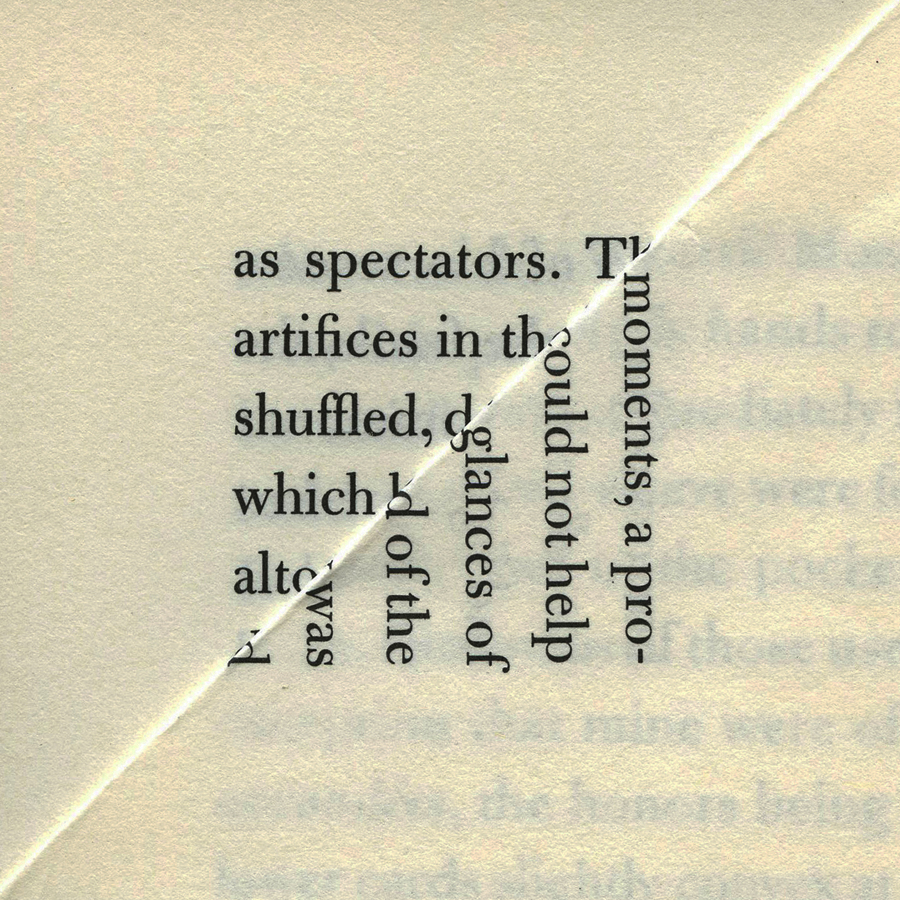

as spectators moments, a pro-

artifices in the could not help

shuffled, glances of

which of the

alto was

Alto which shuffled artifices in as spectators, was of the glances of could-not-help moments, a pro. À propos of Baum’s writerly attention to spatio-semantic structuring, her shrewd framings of various species of printed artifact position her work always in the interstice of photography and poetry. This ambivalence, unlike many of the intergenre claims endemic to her peers, is substantiated by Baum’s work as neither presumptuous nor sloppy; her linguistic finesse is consistently exercised and enhanced by her function as an image collector.

Whether cross-sectioning fanning paperbacks (The Naked Eye, 2009) or extracting stage directions from playscripts (Directions, 2003), Baum collates verbal information with a photographer’s sensitivity to spatial composition. She composes not the words themselves but their field, and through careful excerpting elicits new and generative matrices from the archives. Dog Ear emerges spryly from this lineage, elegantly and methodically resuscitating caches of printed language, over and again, back into the fold.