'The page is slowly turning black'

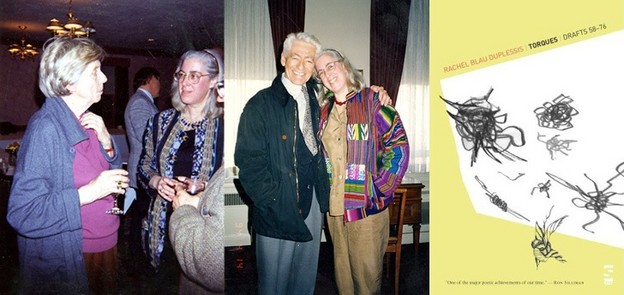

Rachel Blau DuPlessis's 'Torques: Drafts 58–76'

I am always one volume behind in Rachel DuPlessis’s Drafts. Yet, I have been a loyal reader and realize to my surprise that she has been writing them/I have been reading them for the best part of twenty-five years now. We, author and reader, have been “strained companions” in the creation of this work.[1] Often, throughout this essay, I refer to the “writer/reader” of the work to demonstrate the shared enterprise that is an intrinsic part of being in Drafts. Drafts will not yield to you without attention, not just to the individual piece, but to a kind of active, physical juggling, the moving of the finger along the lines of the grid of poems, the reading back and forth within the folds of at least three books. Drafts are a pleasure and a weighty pain as they roll on remorselessly, demanding that you keep up, keep faith and care, that you follow through, follow back and forth, forth and back, reading notes, seeking intertexts, being in the process. We are as battered and elated as DuPlessis herself must be, by the end of each Draft, each volume, each enfolded reading. The poet is aware of this as she challenges, berates and encourages us in the journey. “Are you Ready? are you composed? / Can you go a third Vertiginous road?” she asks with a mocking rather jaunty half-rhyme at the beginning of “Draft 73: Vertigo”[2] (and of course the capitalization of “Ready” makes us see “read,” asks if we are read-worthy of the journey). The whole project is vertiginous in its refusal to cease or fix. I think that my surprise at how long it has all been going on is due not just to the natural human amazement at how time passes, but also to how these pieces still feel so fresh and innovative, so contemporaneous, in their individuality and their structure as a long, ever-changing poem.

This then, is a (rather late) review-essay on DuPlessis’s Torques: Drafts 58–76 and a tribute too from a companion-reader on the other side of the Atlantic. It is also a gathering in and an updating of my own earlier work on DuPlessis, in particular a review-essay of Drafts 1–38, Toll written for How2 in 2002 and an ill-fated unpublished piece from even further back in the mists of time. I also revisit more general essays on which DuPlessis has been influential, one on gender and pronouns written in 2000 and one on “the eco-ethical poetics of found text in contemporary poetry” written in 2009.[3] This then is a revisiting of her words and my words on her words, both of which are interspersed in snippets throughout. As such this essay is written in the spirit of circling and layering through time that DuPlessis’s enfolded Drafts enact and encourage. But I want also to look at what is different, as well as what is continuous, in these Drafts of the early 2000s, at the specificity of Torques in terms of practice, mood, language, and technique. In particular, I identify a growing darkness to the work, the concomitant growing influence of the Objectivist poets, and an increasing tension and richness between complex and simple uses of language in conjunction with each other.[4]

this tensing buzz of poetry (75)

The Drafts project, this “small epic,” is a work of chutzpah, a self-confessed challenge to Ezra Pound’s Cantos (a “counter-Cantos”)as well as a simultaneous, spectacular refusal of the slim volume and the monumental volume at the same time.[5] We are always in the “middle muddle” of the fold and the grid. DuPlessis’s Drafts refer back to themselves along the same numerical line in groupings of nineteen (i.e., 1/20/39/58 or 7/26/45/64). She plans to keep on until 114. Each individual piece of writing however also has its own structure. In Torques DuPlessis continues the Olsonian open form project which is important to her own and subsequent generations. Her fellow poetKathleen Fraser has noted the “immense permission-giving moment of Charles Olson’s “PROJECTIVE VERSE” manifesto” for her generation of women poets.[6] Fraser was founding editor of How(ever), now online as How2, the journal which, virtually singlehandedly, revived the study and publication of modernist and contemporary innovative poetry by women. DuPlessis was “contributing editor” from its foundation in 1983. For Fraser, her Olsonian practice has evolved into a dynamic four-sided page:

the location where an entirely “inappropriate” or “inessential” content might be approached or seized, by fact of the poet’s very redefining of margin as edge: four margins, four edges — PAGE in place of the dictated rigor and predictable pull of the straight, the dominant Flush Left.[7]

In her subsequent book of Drafts, Pitch: Drafts 77–95, DuPlessis does explore the four-sided page in a series of collage poems.[8] In Torques, the left-hand margin remains as precisely an edge, a point of tension against which to push and pull the Draft text to varying degrees of distance, to enact the process of rebellion in text, the inclusion of “unclean … jots and tittles … traces of the Hebraic … debris, rot, fragment.”[9] All this being defined by DuPlessis as precisely counter to Pound’s totalizing and anti-Semitic, anti-feminine systems. Above all, innovation happens in context — form and content enfolded as in the old marriage described by Creeley and amended by Levertov: “form is never more than an extension (revelation, said DL) of content.”[10] Often pieces fold into their construction references to literary and linguistic genres, subgenres and structures as they have been created within the cultural sphere. So, “Draft 67: Spirit Ditties” adopts mock-lyric structures and language; “Draft LXX: Lexicon” is an alphabet-based poem; “Draft 72: Nanifesto” plays with the structure of the manifesto so beloved of the Modernists; “Draft 74: Wanderer” echoes the “books,” the long poem-paragraphs and the complex enjambed sentences of Wordsworth’s Prelude (cited throughout) and “Draft 75: Doggerel” is an anti-doggerel poem written in excruciating rhyme.

Very often homage and ironic critique are embedded in these pieces. However, the Draft structures are not just literary in-jokes. As is fitting for a poet with such a strong social commitment, they bear at least as much relationship to how we should live as to how we should write. “Draft 72: Nanifesto” is particularly notable for this, being largely devoted to social, political, and cultural instructions rather than literary ones (“Critique monoculture”; “Destroy the merely consumable”; “Link the emergencies”; ”Live in empathy”; et al). Whilst there is an affectionate mockery of the manifesto (and of the modern self-help book I can’t help feel) in the “nanifesto,” the advice is sincere as the emphatic and definitive full stop at the end of a line demonstrates.

The poet’s own life is conduit for all this, not too much more. She is pulled from side to side in the torque of her own created structures, as in “Draft 63: Dialogue of self and soul,” which follows a dialectical structure of blocks moving from side to side of the page. There is so much to say and so much that cannot be said, that strong sense of the “unsaid,” that is present throughout Drafts (see the early piece “Draft 11: Schwa”). Here in “Draft 69: Sentences”:

There is so much never to say

filled with gists and drifts.

There was never so much to say

in this tensing buzz of poetry. (75)

There is a sense that DuPlessis is always restlessly seeking structures that reach for the unsayable in ever more challenging ways, ways that might even provoke us to action. “Draft 66: Scroll” has long scroll-like and/or newspaper-like columns — these two textual relations act as a way of trying to pull in the simultaneous rush of mental and emotional material (the “so much”) that DuPlessis wishes to transmit to her readers:

| Not a text and gloss but structured as gloss next to gloss no center, no side, just swerving and looping querying what aspect is marginal how to travel it, how to re-think — |

So much wells up at once, thus a lava-ribbon of text emerged instabilities of liquid rock with fracture, overleafs and turns to what; how ask why this is so: one lives here, now in riddled exposure — (49) |

This section of the unravelled scroll both reflects on its own form (a gloss next to a gloss, speaking or “swerving” back and forth the page across to each other) and considers the possibility of poetic models that might fight or fold their way out of hierarchical structures. Here is the possibility of writing/reading in multiple ways, literally up-and-down and side-to-side here, but also within the larger structure of the enfolded Drafts and the smaller structure of how we might interpret each word and phrase — another set of “strained companionships.”

These forms are not always optimistic in their innovations; the blacked-out sections of “Draft 68: Threshold” carry connotations of (self?-) censorship and decline and take us to a darker place. This is a technique DuPlessis has used before, but more minimally, for example in “Draft 5: Gap.” Here the phrase gleaned from John Cage, “No words for this and these are them,” is made actual in the sustained blackened present/absent words of the poem. The notes confirm that behind the black is “real” lost text. This, to a writer-reader, is a chilling thought, almost reminiscent of book burning. If we read the Michael Davidson glosses down the right-hand side of the page, this effacing of language appears to be a result of the historical conditions “[a]s the war returns.” Davidson is made to critique DuPlessis’s language, or at least to analyze its “Glut and revulsion / truckle the body, / twist discourse” (67). This is a poem of political and linguistic despair, personal in its analysis of the sleeplessness and dreams of the haunted protagonist, of powerlessness and loss. Whereas earlier thresholds or limens have carried elements of hope in DuPlessis’s work, here there is a deathly feel (“Plunge haunted water”), for the whole society and the individual (69). Here is a darkening page for a darkening world.

Darkly, I listen. (22)

Always haunted, DuPlessis’s “langdscape” becomes bleaker, slower, and sadder in this volume.[11] In a short piece about being “Inside the Middle of a Long Poem” written just before embarking on this phase of Drafts, DuPlessis repeatedly describes herself as “haunted” by America’s “compromises, failures and mistakes” as well as by past horrors such as the Holocaust and the fate of outsider artists past and present.[12] Here she locates herself as being “halfway through” Drafts, in which case Torques is the beginning of the second half of the project. Things have not improved. In her “Working Notes” for the “Women and Ecopoetics”special feature I put together for How2 in 2007, she writes that many of the poems in Torques “have had enough”:

Many are written in revulsion towards the Bush regime or coup in US politics and towards the fundamentalist turn in the world at large. Many of them implicitly or explicitly ask what good is it to write poetry. Torques says I am twisted, bent, pulled, under tension, by the political and social reality of Now.[13]

There is a very real sense of crisis here. In the middle of “Draft 69: Sentences,” a Draft which plays out and around with the idea of being “sentenced” to write, DuPlessis asks:

And it isn’t as if this “I” has gotten nowhere,

is it? (71)

It strikes me as an unusual question for DuPlessis to ask. In so many ways, she is a public poet for whom personal angst, haunted by the specter of all those ’60s confessional women’s poems, is undesirable. Even here, the “I” is hedged about with quotation marks. She knows it has no center, but nonetheless there is an “I” who is “twisted, bent, pulled, under tension.” In Torques, DuPlessis allows herself, her “selvedge” as defined against socially constructed contexts, to begin looking back, assessing her career in writing.[14] To any observer, she is a well-published, highly regarded success story, but it is the political failure that she refers to when she asks, “is it?” As such, this is not a particularly self-indulgent question, but a simple statement in line with the Objectivist commitment to “sincerity.” It articulates her “absolute frustration” with the difficulty in fulfilling her ultimate “deeply felt” (another uncharacteristic phrase) desires (14, 70). As she goes on to say in the How2 “Working Note”:

I have been asking myself for years how to communicate my deep social and political questions in aesthetic forms that give pleasure but which also disconcert and destabilize one’s complacency. But I don’t have a lot of answers to that question. I just keep asking it.

I speculate that at the beginning of her writing career this relentless and restless questioning (to which I shall return below), this disturbing of complacency, this disruptive play, was more fun for the poet, a part of her rebellious feminism. It was perhaps more communal too, held in common with the extraordinary community of women poets in the modernist tradition, people such as Kathleen Fraser, Beverly Dahlen, and Alice Notley. Now, as the global political and ecological story darkens, the page is darkening too. Now doubled language is not so joyous:

It is

impossible not to write. Not to; Or to.

Double judgments frozen within

paralysis, which neutralizes its own stasis

into even further stasis. Into minoritized acts.

Sentenced to reject the sentence. (73)

Now, at times, we find ourselves becoming impatient with DuPlessis as she becomes impatient with herself (“boredom with melodrama”), as we become impatient with ourselves (74). In “Sentences,” she berates the reader/writer, both, about the condition of torque:

Luminous distaste.

Don’t make me laugh!

So what? So you are being jerked around

and knotted; so you are roped

and pulled aground.

This is news?

Well, it stays news.

Their masterful escapades

and plundering moves

and thuggish scaffolding

become “your life.”

The title was written with a knife.

The trick is, Watch It.

The trick is, Watch Out. (73)

Torques is full of thwarted intentions and desires, of deep frustrations, of lines which articulate an attempt at simplicity, a simple sense of failure, such as “I wanted to show you things”(19). Torque and thwart are sonically close, and have appeared together before, for instance in the “transverse torque” of “Draft 27: Athwart,” a poem where nature and art fail: an old oak falls in the “tilted force” of strong wind, the hands of the musician “fall athwart,” the work of the photographer Aaron Siskind fails to please the New York Times reviewer who writes “the social world drained from his work.”[15] This is a phrase that haunts the earlier poems, encapsulating perhaps one of DuPlessis’s greatest fears.[16] The word “athwart” suggests an oblique or perverse direction, which, for both reader and writer, once started, “can’t stop / going along.”[17]

Even starting to speak seems impossible now. The very first page of Torques opens, wistfully, poignantly, with the words:

This was to be a beginning,

a beginning, in situ,

that is, in the middle, here. (1)

And of course that is exactly what it is in one way. DuPlessis begins with a relatively small scale personal crisis and links it to the global, drawing a stark simple analogy:

a student jumped from a window

of my workplace

a few tense days before the newest war. (2)

So the book commences with a suicide; the tone is set. Yet these words also lead everywhere, that is, into the twisted public context, and nowhere, since they pose no answers, only questions. The poem ends, “How account for it; how call it to account,” an extraordinary ambition. And of course, DuPlessis has started and over and over again, she must start again, remaining “incipit,” the title of the twentieth Draft and a word that lingers in Torques,chosen for instance from “Draft 9: Page” to form the first “i” section of “Draft LXX Lexicon” (79). She says to herself, to us, we say to ourselves, “Just start” (36). This is an encouragement to others, yet at the same time an aw(e)ful effort. The impatience, the edge of desperation, in “Just start” contrasts with the more hopeful “Begin anywhere” of earlier Drafts.[18] Even in the very last Draft of the book, “Draft 76: Work Table with Scale Models,” this thwarted feel, this sense of the insurmountable “so much,” still has not departed:

I had wanted to write just small, though hungry, sentences,

small.

But so much wells up at once it is like

externalizing a gigantic wall. (133)

The whole archive is an argument. (52)

As the phrase “I just keep asking it” suggests, restless questioning is key to Draft work. From the very beginning, this element of the battering and battered series of more-than-rhetorical questions has always been present. It all began with gender and genre (“who is ‘I’ who is ‘you’ / who is ‘he’ is ‘she’”) and this line of questioning continues in poems such as “Draft 67: Spirit Ditties” which revisits the feminine lyric and narrative structures. [19] In this more recent work however, the restless questioning is most frequently applied to the question of who is responsible for the current “world-system.” In “Draft 71: Headlines, with Spoils” a poem stuffed with references to injustice and “superabundance,” DuPlessis hurls questions at the page:

Who controls these junctures?

who prices these conjunctions?

who mines the evisceration? (92)

A little later, following some found text about “Smart Dust,” a tracking device which may already being used in Iraq, she asks:

Who strews, who reaps?

What is it to be tracked? What catch

to it, what caught? what purpose to deploy?

What haunt imprinted? Who

at stake? Why

tracked? why fought? (94)

This questioning relates to the Jewish tradition of argument and debate present in the midrash of sacred texts such as the Talmud and through the glossing process mentioned above. This cultural tradition also has a bearing on the sense of broken promises or covenants in DuPlessis’s Drafts. These broken social, religious, political, legal, or economic covenants litter our long human history and provoke yet more questions:

What’s the covenant?

who is propitiated

who assuaged? who profited?

The judge fell off his perch

and broke his neck.

He heard the news and lost his balance.

That was the end of valid judges.

Now we are led and judged by monsters.

Where is my place? (38)

By the time of Torques,the disillusionment is stronger than ever, hence the latter part of this citation, the portrait of the crooked judge. Perhaps we are in fact “Covenant-less” (91). Late in the book, in “Draft 74: Wanderer,” she asks:

Should we assume there can be no real covenant,

not given, not imposed, not crazed, but struggled

for and wide? Or should that hope be

given out as gone? (108)

Context is important here — “Draft 74,” a long philosophical wondering/wandering poem, is both intimately bound up with Wordsworth’s Prelude and with the “Wondering Jews” (the title of DuPlessis’s chapter on Jewish culture and religion in her 2001 book Genders, Races, and Religious Cultures in Modern American Poetry, 1908–1934). In an intriguing example of strange bedfellows, the question might well have been asked by both wonderers/wanderers. Indeed Wordsworth might have asked it as he moved away from early socialism into a more conservative old age, not a process we see occurring in DuPlessis’s later years. Rather, DuPlessis’s question, “Where is my place?,” steers us away from the blaming of “them” to the questioning of ourselves as writer/reader-companions. Throughout her work, we have always been asked to “Credit your own complicity” (“Draft 72: Nanifesto,” 96).

Truly World War III or IV is one or two too many (121)

In a 2002 statement written for Pores,DuPlessis draws on Adorno to argue that the political has “migrated into” poetry which should not be “a form of propaganda, but a … part of ideological and discursive practices.”[20] It is not that the Drafts complexify life, as avant-garde work is often accused of doing; it is life that complexifies the Drafts, however much they try to be a “straight-line list.” Yet, as I show throughout this piece, there are moments when DuPlessis consolidates everything into moments of simplicity throughout this text. Torques is not just a speaking, then, but also a response, a “[l]isting and listening” to the historical and apocalyptic moment in which Torques was written, between December 2002 and September 2005 (12). As such, it covers the period in which the US and the UK began to justify their invasion of Iraq, the actual invasion (March 2003) and the first couple of years of the Iraq War or Second Gulf War. It is no coincidence that one of the bleakest poems is “Draft 64: Forward Slash,” which is dated “December 2003–May 2004,” precisely that period when the arguments for invasion were marshaled and then acted upon by Bush and Blair.

But it is war in the bigger sense, the justification and endless condition of war, that concerns DuPlessis in this “little epic” (134), just as it was for her important predecessor H.D. in her long poems engaged with the arguably masculine epic form, Trilogy and Helen in Egypt. “Draft 61: Pyx” asks:

What war?

You think you thought you know.

One in which you were born

or borne or bored

or bode

embodied (28).

“Draft 62: Gap” is written “November 2002–January 2003 / Before the U.S. Invasion of Iraq” and looks back to the Second World War as well as forward to the Iraq War (34). And it continues the

Listing and listening

— a great swath of names and citations

and the question what were they

what had happened

these suffering bodies

riddled and scarified, bandied, branded (12)

Reading DuPlessis writing, the sense of the absence/presence of the dead has always been powerful. It may be her predecessors, women and modernist poets, whom she is calling on: “alas, they cannot hear / although we talk to them” (7). More often though it is the hordes of tragic dead, the war dead, the massacred dead, the starved dead to whom she has a duty and also a longing which can’t be fulfilled. DuPlessis’s Jewish heritage is surely influential here, the Holocaust having always been present in her work, particularly in the Gap poems along the line of five. She has this memorializing in common with Objectivists such as Charles Reznikoff and more recent poets such as Jerome Rothenberg.[21]

This then is a journeying into the past, an act of mourning, both of which are intrinsic to the Demeter/Persephone or Kore (the name of DuPlessis’s daughter) myth, a touchstone throughout her work. “Draft 61: Pyx” is a particularly ghostly piece. Here, in a reversal of the myth, the underworld surfaces into the “real” world: “and when the page turned back / an underneath came up” (22). Yes, it is “back” here, but the shadow word, the aptly invisible word is of course, “black.” Again, a darkening page for a darkening world. The unsaid, the silenced in DuPlessis’s work, is most often associated with the words the dead cannot speak:

How is it? I said: that the ghosts are so gathered?

Because they are palpable and present

buried wounds

the names that cannot rise and so they turn

and come as darkness thickened without sound

These shadows make antiphonal claims

as words that fail. (“Draft 61: Pyx,” 29)

In “Draft 64: Forward Slash” the writer/reader becomes a ghostly figure (“Blank Rachel … / I too am a stranger … [among] other shivering walkers”) and there is a sense of hopelessness by the end of the poem:

Ghost. Yes ghost. This one not complex.

Just the shadow isle of sunken hope and text. (43)

Here, at the end of this piece shadowed by the Iraq War, we find another of these simple moments, where the end of hope, depression is deathly but, “not complex.” Where the wanderer includes the poet/speaker herself, we begin to see a blurring of the worlds of the living and the dead:

As for R, like a revenant, I wandered

far and wide

reversing, and revering

the streets and cemeteries

of the dead

and I saw the Monuments

to the Deported

stark inside me

as in a city … (24)

The reference here to “Deported” is also of course to the departed, but it brings in another realm of the deathly: the deported, displaced, exiled, homeless people who exist in other lands from their home(land) or whose land never feels like home, in particular of course the Jewish immigrants to America whose cultural depiction in early twentieth-century poetry was largely one of disgust and pollution, as DuPlessis has charted.[22] These wandering/wondering souls, strangers and revenants, neither wholly dead nor alive, frequent the Draft poems of Torques: “Revenant, tell me if you know / what land am I? and you?” (92). Perhaps, again, the Objectivists were also in DuPlessis’s mind, many of them being Jewish outsiders, exiles or immigrants in America. In “Draft 66: Scroll” the revenants keep vigil together, recovering their own memories or “epiphanies of mourning” through the music of Shostakovich (49). This is a reference to an actual incident, but is broadened here, woven into a wider picture of reasons to mourn as it looks back to the war and forward to our future mourning in the face of environmental disaster.

roam the groundwork of resistance (84)

Arguably DuPlessis’s Drafts have always been ecological in the broadest sense, their strong sense of “Out there / connected / to the over-here” being an essential element of environmental thinking, in particular the environmental justice movement (93). Her disgust at consumerism (“malls a homey homeless home / ahung with things”) has been consistent, and she traces these “signs” back to the origins and conditions of cheap labor.[23] Her practice, too, the use of intertexts and scrupulous notes from a wide range of sources, literary and cultural, has, as I have argued elsewhere, the humility of recycling, about it, the poet replacing the great romantic myth of originality, the poet as genius, with the poet as reuser, recycler of words.[24]

Inevitably, as our knowledge of the environmental crisis grows, that sense of “out there […] over-here” has led DuPlessis to reference environmental issues more in her work. “Draft 53: Ecologue” (written in 2001 and published in the previous volume of Drafts) foreshadows many of the ecological concerns of Torques.Here, the factual inclusions, the material that cannot be assimilated, is often that which reflects on the deterioration of the ecological situation, as in this left-hand side column of “Draft 66: Scroll”:

“If this ain’t yours, it’s no one’s”

trans-generic bacteria, plus us

need 4 more planet Earth’s

to all consume like U.S. citizens

So yell “Trigger Treat”

without fraying, or unravelling

Folded inside these intricacies

it’s collateral wreckage

Is this the Tentieth Century? (48)

DuPlessis references E. O. Wilson’s The Future of Life here in a passage that projects into the future a sense of where an American-influenced future may lead us if we do not shift the trajectory of progress. I read “the Tentieth Century” as a reference to the tented communities of climate refugees we already see and which are more likely to grow than diminish.[25] This cannot be dissociated from our fundamentally capitalist and consumerist “world-system”:

| Patchy roads and fast foods educational outlets in strip malls pinguid gluts, unknowable nauseas Shopping binge Read the signs as you walk read them, trying to figure how branches suggest the menace of marks |

Failed development paradigm arousal to justice deferred given box stores filled with stuff Cheap as blood, vigil memory error theater plastics choking both ruthless failure and unspeakable forgotten hopes (49) |

America is grotesque here in its adherence to “stuff” and the real cost appears in the words “blood” and “choking” which reference the attendant human and environmental disasters behind the “Forlorn shoppers’” endless deathly quests (51).[26]

“Draft 72: Nanifesto,” which has “Ecologue” as one of its donor Drafts, is immediately and recognizably ecological in approach from the very first lines:

Insist on smallness.

Scale down clutter.

Critique monoculture. (95)

The political work of DuPlessis’s Drafts has become a call to “groundwork” also.

The counterbalance to consumerism, that is the “natural” world, however hedged about that term must be, has not had much of a presence in DuPlessis’s work to date. As a predominantly landscape writer myself I find it exciting to see nature creeping in, as if DuPlessis has been led back to “nature” through environmental politics. In “Nanifesto” we have “compare the properties of reeds”; “Respect honey and, even more, the bees”; “Investigate wild asparagus, for it grows oddly”; “Hike in strong boots to wherever a good there is” (95–97). In her Wordsworth poem “Draft 74: Wanderer,” the emblematic nature poet is referenced throughout. Here she creeps beneath Wordsworth’s breathless big scapes to create the nano-image of two fucking butterflies (109). As with the bees of course, it is the threat of loss of nature that makes us consider its “worth,” Hence, the litany of apple names DuPlessis cites in “Draft 53: Ecologue” and her reference in “Wanderer” to “as many kinds as still can grow despite industrial agriculture (119).[27] Although he is not included in her notes to either poem, this recalls for me Thoreau’s 1850 essay on “Wild Apples,” which mourns the loss of native fruit and dwells on apple names and histories real and created.[28] Here DuPlessis adds the actual apple to the cultural apples (the apple in alphabetical primers; the mythological “apple of discord”) which appear throughout Drafts (see 65, 77). In keeping with the twist and thwart of Torques the apple’s last appearance in the book is as “A for apple” for “anger” and for “anguish” … “This being what it is.” (119).

Place, from planet to locality, is referenced throughout Torques. In “Draft LXX: Lexicon” “P” reveals a cluster of words around “place”:

This pulsing present

cowers

watching current performance of Powers —

This place, this place. Poor planet I pray,

perhaps preaching

quote unquote

only to the quire

but Ready to be ready.

Reaching, wretched, returning

to roam the groundwork of resistance. (84)

The fear of preaching or being perceived (“quote unquote”) as preaching is common to environmental campaigners, as is the need to refute the idea of environmentalism as a form of replacement religion with “holier than thou” elements. DuPlessis explores this here, not least through the reference to “quire” a word we can read as a musical church choir or as a quire of paper, her particular materials. A little later in the poem, she identifies another problem of eco-action which is the emphasis on “saving” a particular locality (usually a space enjoyed by middle class people on recreational activities):

Are these trees here

more sacred trees

than any other trees? (85)

In the face of the threat to our planet, our feelings about it have changed radically and this is reflected in DuPlessis’s recent poems. Although there is presence of abyss in early Drafts, there are also joyously choric wide poetic cosmological spaces/pages for thinking/performing: “Here is the space for action, a theatre, a page, a white space in which voices, marks, words and letters will move, sound and think in a dynamical performance.”[29] “Draft 26: M-m-ry,” for instance, begins:

That the airy opening hung somber, / that the moon

trapezoid / on the floor be thus, be / here,

that musical/ logic in

the hypnogogic space / come waves rush/

crosswise, athwart ….[30]

Contrast this to the remorselessly bleak references to space and the planet in Torques:

a planet

desiccated, decimated.

with what ? empires? profiteering?

sheer misuse? (31)

Tonight the planet earth, one total thing,

will cast a brownish stain

over our intimate, the big-faced moon. (37)

Picking up on the references to pollution and poisoning present in the enfolded “Draft 47: Printed Matter,” “Scroll” is scattered with little words and phrases that heighten our sense of a present and progressive global crisis (“extinct orioles,” “thinking beyond / our air rights), all of which culminates in a final image of the “half bleak, and half-pending / Tainted Spot,” our fundamentally polluted planet (51).[31] There is an awareness too of the comedy and hubris of human expectations of nature in this work. In the second part of “Draft 63: Dialogue of self and soul,” the poet awaits an eclipse, but will it meet her expectations:

It looks to be going

into deeper umbra

What is darker; what is lighter

Will these clouds move?

Was this the hope, or that

Am I seeing it? (39)

Possible, word by letter, letter by word (75)

In “Draft 69: Sentences,” just before the drastic cutoff (“But this poem has to exit. / This is enough to mourn. / Impossible to stand it.”), a tiny hopefulness seeps into the poem in the form of more spacious lines which say:

Possible, word by letter, letter by word,

trying to true, again to enter and

engage the saturated task. (75–76)

The hope in DuPlessis’s Torques is only through the micro-tools of the work, the little individual letters and words. I’ve always loved this element of her work, the bringing together of the micro and the macro, the single letter in the big-scale poem. I ended with this idea in my last essay on DuPlessis’s Drafts and toyed with the idea of starting with it here, except that I wanted to foreground, first, the idea of an ever-darkening page against which those letters still dance. In “Draft 63: Dialogue of self and soul,” DuPlessis refers to her own project:

19 columns of impacted writing

are indexed under 26 letters.

why zero in on one?

I’d hardly say that letters

do not matter, their brilliant serif-im as fire,

but thinking only of design, of mystical nets,

will not absorb the imprint of our time. (36)

And yet, right through Torques, she does precisely “zero in on one,” or different single letters and pairs of letters, additions and omissions of letters from words. In this, she is consistent with earlier work, although the individual letters’ peculiar significances are often specific to this book. There is a primer element to this that is not new. From “Draft X: Letters” onwards, “A” is “Always apples / are (r) / first /… A / premier symbol / on the table.”[32] However, in Torques, although apples feature as we have seen, the “premier symbol” of the primer here is surely “N,” the principle of negativity all too alive in the world:

noman, nomad, nogirl, no good

just the sheer N of no. (5)

These lines come near the bleak close of the very first poem, “Draft 58: In Situ.” Add one letter and “Not is as good a mark as now,” a sad picture of the present from “Draft 61: Pyx” (31). The lyrical “poetic O of moon” of poetry is subsumed by “N” in “Draft 63”:

one letter beyond N

and completing the NO

perfectly?

Or perhaps the P of Paralysis? (36)

So in a cluster of oppressive associations, “N” is no, “P” is paralysis, “C” is complicity or collusion (77), and “V” is vertigo, void, and a sinking raft of other Vs in “Draft 73: Vertigo,” a poem infused with a sense of loss, flooding, and abyss (98). Here too we see the saved letters of DuPlessis’s daughter as an infant, less endearing than “stark” and “formless” in their suggestion of “another other trace, or mark, or sign” that is “beyond one single alphabet’s entanglement.”

But then, just as we feel our alphabet to be “in the void” (129), there is “H,” the great Hope of Torques:

I wanted a whirling list of hopes

hopes hopes hopes whole alphabets of H’s

to evaporate and leave the sweet encrust,

a deep powder; a power inside the poetry … (17)

The fantastical idea of an alphabet of one letter is alluring, funny, magical: all elements which come into play in DuPlessis’s letters. The hope is not achieved in this poem of signs, “Draft 60: Rebus”; it is dissolved into M for (quoting out of line sequence) “moaning … muttering … misery … merciless management … Malarial muck for drinking water” (19).

However, “hope,” almost secretly, in spite of itself, is a powerful force in Torques, as it flickers in and out of the poems and pages. Look above.In the darkest pages, we have already seen it (quoted in the order cited in this essay):

Or should that hope be

given out as gone? (108)

This one not complex.

Just the shadow isle of sunken hope and text. (43)

the menace of marks and unspeakable forgotten hopes (50)

Was this the hope, or that

Am I seeing it? (39)

Ultimately, in another moment of simplicity, DuPlessis writes:

Not to see hope

is damaging

To see it, but deluded, could be worse. (112)

So “H” is the only counter to “N.”

In “Draft 66: Scroll,” opposite a compressed “field guide” to ecological disaster (“urgency,” “Post-consumer waste”) appears the “gloss” on the human side of the equation:

both ruthless failure

and unspeakable, forgotten hopes

that alphabets nonetheless pleat and

gather.

Political autism and Rage

in tempore belli

with burning and dodging techniques

so where is our N to stand? No where?

need clarity of Letter exfoliated … (49–50)

Here, in our zone of perpetual war, the H of Hope and the N of No are in dialogue throughout Torques. Like Persephone/Kore, we feel the “undertow or undertone” of the “U” of Underworld pulling us down, only to find touches of “H,” of Spring, again (85). The scroll goes on to note how these scrolls of letters “hardly suffice / for a smallest local hope” but yet hope always starts “again and then again” in a process of albeit haunted “arousal” and re-arousal:

To start

Again. Not again! In the imperfect moment

again to unroll the scroll

like this. In Yet and Yes. Id est:

all the letters, N and Y, J and A,

X, and explore intricacy along the way

e.g. inside necessity (51)

If we can find hope in these dark pages, then:

Why rip the books?

The books, the books contain our hopes.

To rip them

is to concede

to grope. (73)

“H” and thus hope is often linked to home, as these extracts from the alphabetical “Lexicon” poem illustrate:

sight of that home, or hone, shimmering

among bristled haulm of

the Irretrievable; the Inchoate; the Impenetrable …. (78)

Hard to tell which hungers hinge to home. (83)

Hope and home then may together provide a mental homeland for the tragic wanderer/wonderer revenants figures who haunt the pages of Torques,as well as the reader/writer herself.

injustice, rage, despair (12)

The word “hope” from DuPlessis’s individualized primer draws our attention to the place of abstract nouns in Torques. “Go in fear of abstractions” was Ezra Pound’s advice for would-be Imagists, but DuPlessis, lover of modernists as she is, has many reservations about Pound and his prescriptions. Her abstractions are not frequent, but they are all the more simple, strong, and purposeful for that. They stand, amidst the varied and various vocabularies of this poetry, for what they are, for inassimilable human emotions and concepts. They are self-conscious, always edged with irony, as in this citation of perhaps the biggest abstraction, “truth,” mockingly arranged to raspingly half-rhyme with “laugh”:

The truth? It’s true.

Although I also laugh. (12)

In “Draft 59: Flash Back” it comes down to:

Where is justice?

How to get it? (13)

In the Lexicon poem discussed further below, “J” is once again unequivocally:

Justice,

Just that. (87)[33]

DuPlessis must be one of a very few contemporary poets who have set out in the public sphere a clear set of political values adding up to “Justice”:

What are my political values? social justice. gender justice. equality of access to reasonable living goods. economic justice, which means an equalization of society. … Access to education, to health care, to social goods: genuinely and liberally available. No despoiling of the earth, and the living creatures on it (including us) for profit. The call for an end of global crimes: of exploitation of child labor, of capturing people inside prison-model factories, of the destruction of water, animals, plant life; of the poisoning of people at work by their work. Development without despoiling. Justice. justice. justice for all … All this means post-capitalist, and post-nationalist values.[34]

Whilst DuPlessis’s enfolded Drafts have always embodied a ceaseless quest for an unobtainable, this has become more generically associated with social justice and less with a specifically feminine quest.[35]

Nonetheless, as always, DuPlessis is confronting gender expectations, and this very use of abstract nouns is one of them. This reclamation of emotion flies in the face of the snide, dismissive approach to female emotionalism in critical thinking. Conversely, in her essay “Corpses of Poesy” DuPlessis finds Pound’s praise of his fellow modernists Marianne Moore and Mina Loy for their lack of emotionalism just as problematic. He fails to recognize, she notes, their “passion, sarcasm, anger.” [36] In DuPlessis’s own work, she openly and confrontationally claims these very feelings. More often than not, what we find in the quest for “J” is “R,” a series of variations on the theme of rage: “impotence, rage, solemnity, paralysis” (4); “injustice, rage, despair” (12); “rage and grief” (50). In DuPlessis’s “Draft 72: Nanifesto” she upholds the dark or negative virtues: “Do not fail sadness”; “Persist in negative care”; “Work in anxious panic”; “Keep the rage complex”; “Credit your own complicity” (95–96). Rage is the keynote dark virtue here, right through the volume: “Enraged by our time. That simple” (14). Many of the poems are written in rage, committed to rage. “Draft 71: Headlines, with Spoils” asserts:

To keep track of grievances means living in fury. Forget

recollection in tranquility. Try collection today. Any day will do. (93)

To sum up, R=N+H=R.

Since every word is three (11)

Letters make words. The consciousness of every letter’s place within a word allows each word to multiply into a host of words, a plethora of portmanteaux, of homonyms and homophones, of newly created words, of words within words within words, just as in H.D.’s Trilogy :

… I know, I feel

the meaning that words hide;

they are anagrams, cryptograms,

little boxes, conditioned

to hatch butterflies …[37]

Often every word is three, DuPlessis’s much-quoted (by me, at least) “both and and.”[38] This allows “bountries” to be “bounty-boundary” but also the unspoken countries (13). Invariably the word not said is the one we might have expected: for example, we hear “coincides” when DuPlessis writes “co-insides” (13). Equally, the split words “BEG IN” and “IN STILL” create richer meanings in context (22, 30). Sometimes, both pairs of a homonym are set side by side: “one rancid day of mist or missed” (42). The slippery process also occurs between languages: “COMME SI” and “COME, SEE” (104). This is sonic too, of course, adding to the caressive quality of DuPlessis’s touching and tasting, the “play-splice” of language, as in “parling, parting” (107). It has also always been “a punning metonymic chain of connections (absolute poison to her detractors) to ‘get over’ dominant language,” a process of decoding and rejuvenation giving “access to the language ‘inside’ the language, suggestively occult, suggestively female.” This description comes from DuPlessis’s analysis of Trilogy inher 1986 monograph, H.D.: The Career of That Struggle.[39] We can see how H.D.’s technique must have influenced the early DuPlessis who spends several pages of this densely packed book on this passage. For H.D., the spiritual dimension of the process was at the fore as she shifted her way through Greek and Egyptian mythologies:

For example:

Osiris equates O-sir-is or O-Sire-is;

Osiris,

the star Sirius,

…

recover the secret of Isis[40]

For DuPlessis, as a “realist and materialist poet” in the “Objectivist continuum,” spiritual consolation is scant.[41] She does not oppose female spirituality with “masculinist-nihilist / materialist positions,” as she describes H.D. doing.[42] Materialism is no longer masculinist in DuPlessis’s world. Yet, describing herself as a secular Jew with grave doubts about religion, she nonetheless writes in Pores: “I have a debate with modes of transcendence; I live in materiality which is nonetheless filled with sparks of awe (Niedecker).”[43]

DuPlessis rejects the “female figure of power at the center of the poem” that she finds in other women writers’ work, including H.D. For her the redemptive comes through the eroticized “repetition and crumpled touching” of both the enfolded grid of poems and of language within the poems — this is the sustaining force in her work, even if in Torques it must fight against the sense that even poesis as polluted.[44] In the final poem of the volume, “Draft 76: Work Table with Scale Models,” there is a redemptive return to the erotics of fold and language “with its ferocious flood of desire and demands” (132):

The talismans of this or that are handed round.

Their “folds come to contain the flow of time.”

Fold to flow, come to con-, tain to time.

Beautiful. Really.

And this is also a theory of debris.

Not ironic, but saturated in irony. (133)

Here the “Beautiful” refers not only to the Charles Altieri quotation (“folds come to contain the flow of time”), but to the slippage of language in “Fold to flow, come to con-, tain to time.” DuPlessis is revealing the poetry in the original quotation and also creating a new line whilst revealing the beauty of the whole slippery process. The “Really” and the emphatic full stops after each word of “Beautiful. Really.” acknowledge the shock that this emphatically positive abstraction is to us after the abstract nouns offered previously. Before this point, the only instance of the word has been the cutting:

They say: it’s so beautiful

couldn’t you do better? (16)

Real beauty is often found in the change of one letter in two consecutive words, “a deep powder; a power inside the poetry” (17). The lyricism, eroticism, and significance of poems increases with this multiplicity. Wander and wonder recur in Drafts and in particular throughout “Draft 74: Wanderer.” This allows for the conflation of mental and spatial journeying which characterize the whole collection. I have a weakness for DuPlessis’s alliterative or more complex sonic pairings, often in lines of four, such as “knit and knot and gloam and glare” (1) and “pinch and poke; poppit, prime and pry” (115). Not surprisingly, we find them too in the mock-lyric poem “Draft 67: Spirit Ditties”:

Bite and bark

trunk and leaf

rune and turn (53)

This can also act as a lightening influence through quickfire humor, such as the witty reversal “fast drivers in fat cars” (40). “Draft 61: Pyx” is a darkly comic take on male authority in academia, featuring lines such as:

He tapped his cane, surrounded

by other men

showing the faculty or facility … (21)

Here we also have the wonderful “avant garden” (23). On the very next page, though, the word slippage is much edgier as the woman poet sends her lines out into the world through “a process of greeting / of gritting” (22).

Something that sort of ends, but sort of not (8)

There are bigger structures for letters than words. Individual letters are commonly perceived as part of a collective, of course, the alphabet with which DuPlessis has always had a love-hate, playful relationship. Structures are always under question in her work. In “Draft X: Letters,” referencing William Carlos Williams, she constructs a letter poem ordered on the typewriter/keyboard sequence, left to right. Yet, although this is a QWERTY poem, many of the letter sections seek X, the mystery letter of the title and under X, the whole alphabet returns plays out again. No structure is singular.

“Draft LXX: Lexicon” in Torques is another letter poem, this time based on an individualized alphabet made into a fold/grid experiment. Here DuPlessis draws letters and words from Draft 1 in the A section, 2 in the B, and so forth. This then is a numerical as well as alphanumeric experiment which produces not one single whole alphabet as in a primer, but two and two-thirds of an alphabet, finishing at “r.” It is also a fold within a fold, since it divides the previous Drafts into groups of twenty-six, rather than nineteen, thus becoming “amusingly complicated” (140). The words and letters of the enfolded Drafts, the full “langdscape,” return — they become themselves revenants, ghost words, and yet, used again, are of course also new in context. The procedure of the poem is to join up letter sections rather than to separate them, so “Lexicon” becomes a flowing, self-referential piece on writing past and present as can be seen in the example of p, q, r cited in the discussion of place above. As I have demonstrated above, we can also read out from “Lexicon” into the rest of Torques itselfin order to identify important word clusters around letters, just as the “P” reading as place links into the environmental thread of the volume (84, 90).

In “Draft 59: Flash Back” DuPlessis returns to that suspicion of preordained structures for thinking, including the alphabet. This “question” inaugurates a series of speculations on alternatives:

Question:

Why use the alphabet to organize,

and why not? Discuss.

Suggest another mechanism of order.

One form and then another.

Something that sort of ends, but sort of not. (8)

The alphabet was used by Brian Kim Stefans to create an animated text response to DuPlessis’s statement on gender and sexuality written for the Buffalo Poetics List in 2000.[45]

In his note to the piece, “The Dreamlife of Letters,” Stefans describes DuPlessis’s original text as a “texturally detailed, nearly opaque response” to the questions posed by Dodie Bellamy for the online roundtable. Another word Stefans uses about it is “loaded.” One could read DuPlessis’s critique of the alphabet as a critique of Stefans’s certainly frolicsome but rather lightweight transfiguration of DuPlessis’s work. In her note to “Draft 59: Flash Back,” she remarks that Darren Wershler-Henry asked Stefans in interview whether the work “did not compromise the feminist speculation in my statement” (137). Certainly to me “The Dreamlife of Letters” seems to articulate an attempt to avoid the difficulty that DuPlessis’s original text poses, to lighten the dense “load,” if you like. DuPlessis’s life and texts are not light (one is tempted to cite Dickinson’s “my life had stood a loaded gun” here), and the alphabet, like all other systems, is under question. The deceptively simple statement “It is not one Anything,” the more one dwells on it, is deeply radical in its resistance to preordained structures of any kind (9). They always lead to loss, as more restless questions suggest:

Who has designs on us? and Why?

What is the force of our conviction?

Something has gotten away from us:

urgency for justice, intensities of ire,

lime-green as the after-image

in the eye-teeth of unrhymable orange. (9)

Here again, DuPlessis references “The Dreamlife of Letters” which Stefans described as a “flash animation poem with a twist of avant-feminist lime” and which is set against a bright orange background (137). Note the abstract absolute, Justice, again. By the end of this Draft, after considering the various effects of her animated words, DuPlessis feels perhaps, as I tend to, that contemporary web poetry has a long way to go. She returns to:

A page: where every line stands up affright

porcupines that run ahead

in sudden light. (10)

Dry tears over blood-type headlines? (12)

We have seen in the discussion above that DuPlessis moves between her usual shifting language-play associated with poetries associated with poststructuralist practice and a more urgent direct language “(This one not complex”), including manifesto dictates, philosophical statements, and abstract nouns. There is a continuing struggle to work out what language will rise to the challenge of the times, which is heightened in the torque or twist of this volume. In “Draft 69: Sentences” (which follows the blacked-out “Threshold” poem), language is “corrupted, corrupting/ corruptible” (70). In the face of the temptations, risks and slipperiness of poetic language, at times all we can do is collect textual evidence:

Impossible to write a poem.

No sentences can be made.

Social founders, kitschy gabble.

No collection mechanisms seem engaged.

except razoring facts from the newspaper page

to which I am sentenced. (70)

Of course, the poem moves on, as it always does, to speaking of multiple though often agonizing ways of writing, but I want to stay with the newspaper facts here, with DuPlessis’s habit of “razoring facts” from the papers in order to pull the work into focus or clarity (another Objectivist word), in order, perhaps, to give reasons for all that rage:

“12 hours per day for a pittance, living

“12 to a room, working

“in fenced-in factory complexes,” (92)

We can read “razoring” here as a verb (as in cutting from the paper) and as an adjective (facts which are painful for us read). This is part of the “listing and listening” to the “great swath of names and citations” and the accompanying restless questions: “what were they / what had happened / these suffering bodies” (12). Right through the Drafts project, to tell has always been to toll, and this title was chosen for the gathering together of the first books of Drafts into one volume, Toll.[46] In “Draft 73: Vertigo,” “NOTHING IS EVER ENOUGH / even into extended telling, even unto toll” (103).

This collection of testimony, of evidence, is reminiscent of the Objectivists’ enterprise, the attempt to remain true to what Louis Zukofsky called “inextricably the direction of historical and contemporary particulars,” found text being one example of how this was achieved.[47] The most extreme example of the incorporation of factual found text into poetry is in the work of the Objectivist Zukofsky saw as working at the height of “sincerity”: Charles Reznikoff. His poems Testimony and Holocaust are based entirely on found text selections from courtroom records.[48] The British poet Anne Stevenson wrote of Holocaust that “No poet has ever written a book so nakedly shocking, so blatantly calculated to make us feel that the Nazi persecution of the Jews can never be fictionalized or abstracted into “literature.”[49] DuPlessis asserts, regarding Reznikoff, that “there is a political agenda in simply confronting readers with a record of hurt and wounding.”[50] In other words, no fictionalized or poetic words could break through our defenses as effectively (“NOTHING IS EVER ENOUGH”).

So, as these lines from “Draft 74: Wanderer” illustrate, the poet turns documenter and witness:

who want to speak to sigh, to sigh and

rage, not for that hour, not for that place

yet nowhere

unembellished by some trace:

documentary (that and more) witnessing (that

many more) and witless, hurtful “jesting air” — en-

joined, frozen in motion but not to crumble, rather

stand. (106)

The singular “want” both asserts this desire and, through the shadow word “wants,” asks who could want do this work, a doubleness or ambivalence we see throughout the volume.

At the heart of “Draft 69: Sentences” and the heart of Torques itself, DuPlessis muses on not being a journalist with an official role and place to speak:

I have no press pass. No credentials. Not embedded.

That stands at the margin of edge

without particular brands of “I”

to greet you with.

Only you alone are listening,

perhaps; and thanks.

Or maybe not, can’t count on that. (71–72)

Yet that edge-position allows of course for the ability to recontextualize the facts of journalism, to present them to us so that we see them again, more clearly. I have written elsewhere about the sense of anger and powerlessness that often characterizes how we feel about the world, particularly environmental, issues that face us now.[51] As our knowledge and concerns grow ever less national, more global, we are increasingly dependent on news media. When we turn there, we are bombarded by narratives of disaster and apocalypse. Particularly in relation to climate change, there is a danger of not just helplessness and despair, but also, most dangerously, desensitization. In his essay “Climate Change and Contemporary Modernist Poetry,” Richard Kerridge, via Slavoj Zizek, has noted how our response can never be adequate since we are dealing with material beyond “our most unquestionable presuppositions,” such as “our everyday understanding of ‘nature’ as a regular, rhythmic process.”[52]

DuPlessis considers how we might remain sensitized to the world and the possibility of action with it in her working notes for How2. She picks up on “will anything teach us?,” her own phrase from Torques (85):

Will anything teach us? A poem with both affect and information has as much chance as anything to give rise to understanding, via an incantation of words that turns the mind, deturns our thinking, makes us face our world, and, perhaps even motivates us to political action.

She refers here to the Situationist practice of detournement, a practice of “appropriating” and “turning” of public language. For Raoul Vaneigem, the Belgian Situationist, detournement involved “acts … against power” requiring tactics “taking into account the strength of the enemy.”[53] For Guy Debord, this included the “negation and subversion of ‘official public language’ that “conceals and protects” the public world. Through her use of found text, found poetry and poetics, DuPlessis practices this “turning back” of public language against itself, a process that should “inform” as well as satirize or emotionally affect. Perhaps she is thinking here of Debord’s statement that “Information is power’s poetry (the counterpoetry of the maintenance of law and order)” (102). Arguably, DuPlessis determines to recapture information for poetry. Within “the vast plethora of news that washes over us” is the news that we need to hear and digest. That plethora of “dark news” is a continual presence in Torques, darkening the page in forms (especially the scroll draft), uses of language, and numerous explicit references (130):

IN STILL

Sovegna vos,

rem-Ember

and thereupon open

today’s

newspaper

A rush of people across a bridge:

grift, happenstance, war, drought, need

mortal life washes us up on its shores

somber and singing

cracked hordes, cracked lips (30–31)

A few pages later, as she often does, DuPlessis condenses this as “grief the news and rage,” surrounding “the news” with “grief,” echoing the “grift” above, and the all-important motivating “rage.” This is the “checkered Now” (108) we have to meet, the “historical moment,” but the beginning of this extract emphasizes again how these present crises originate out of the past, hence the necessity of memory implied by the vocative “Sovegna vos”: you should remember. Interestingly, DuPlessis removes the other half of this Dante quote as cited by Eliot in “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” Here, “Sovegna vos al temps de mon dolor” is a far more self-indulgent expression of woe, of “mon dolor,” not everyone else’s.

“Draft 71: Headlines, with Spoils” is a striking example of the use of news headlines, cast in a “larger, darker font size [to] underline our condition” and to resist the “washing over” effect, to produce poetry which combines “information with feeling.” The phrase is important. DuPlessis does not hold back from exploring emotion or psychological affect, as Reznikoff does in his testimonial work. In many ways DuPlessis is closer to what herself describes as the “psychosocial” cultural poetics of the only female objectivist, Lorine Niedecker.[54] She speculates that Niedecker’s interest in the psychological and emotional resonances of language and politics might relate to her gender and social difference from the other Objectivist poets. I speculate that DuPlessis herself might identify with this, in particular what Niedecker describes as an “awareness of everything influencing everything” which, near the end of her life, she no longer fears might just be “goofing off.” Perhaps too DuPlessis finds inspiration for her developing environmentalism from Niedecker’s own.[55]

In the following lines from “Draft 71: Headlines, with Spoils,” the factual headlines stand out and the lines in quotation marks acquire an irony in context:

Night sky, wet roads; headlines thick,

big-font lines, the whole shtick

in I Ching throws.

Auto and plant emissions linked to fetal harm

bling bling — “linked to”

but, as stated, “no cause for alarm.”

…

There is a garish palette of superabundance at an undisclosed location.

Shopping binge compensates for a low industrial sector

Buy enlarge.

Freedom of Choice! (“linked to,” as stated, “no cause for alarm”)

And then the prototype robot-soldier

“readied, aimed and fired at a Pepsi can,

performing the basic tasks of hunting and killing.”

So That:

This work will never hit

the post-production stage,

because

Tanker Sinks Off Spain, Threatening Eco-disaster (91–92)

DuPlessis’s headlines are attributed to sources such as The Philadelphia Inquirer and International Herald Tribune. Without sacrificing subtlety and context, DuPlessis makes us feel that our response is demanded and should even be translated into some kind of action.

We have come full circle here to my first point about Torques: that form and content remain closely engaged in DuPlessis’s work and that she succeeds in evolving both her structure and language to meet the needs she sees around her, drawing as she has always done on the work of the previous generation of modernists and making it speak again, afresh for the here and now. Although the Draft project reflects back to us a darkening social condition which sometimes we would rather not confront, it also demonstrates the ability to respond. At the end of “Draft 61: Pyx,” there is a casting asunder of all the barriers to speech, one of those moments when words coalesce into one last incipit, simple statement:

Forget “other.”

Forget “marginal.”

It is this very site.

It says “Sit down in it.

It’s time now.”

Now it’s time. (31)

1. Rachel Blau DuPlessis, “Writing on ‘Writing,’” in Tabula Rosa (Elmwood, CT: Potes and Poets Press, 1987), 84. I have always read this piece as a prologue to the Draft body of work, almost a declaration of intent.

2. DuPlessis, Torques: Drafts 58–76 (Cambridge: Salt, 2007), 70. All subsequent page references within the text are to this volume. References to other volumes will appear in endnotes.

3. Harriet Tarlo, “‘Origami Foldits’: Rachel Blau DuPlessis’s Drafts 1–38, Toll,” How2 1, no. 8 (Fall 2002); “‘A she even smaller than a me’: Gender Dramas of the Contemporary Avant-Garde,” in Contemporary Women’s Poetry: Reading/Writing/Practice, ed. Alison Mark and Deryn Rees-Jones (Houndmills: Macmillan, 2000); “Recycles: The Eco-Ethical Poetics of Found Text in Contemporary Poetry,” Journal of Ecocriticism 1, no. 2 (2009), special issue on “Poetic Ecologies.”

4. The growing Objectivist influence must also of course be related to DuPlessis’s work in the late nineties (shortly before writing these poems) in coediting The Objectivist Nexus: Essays in Cultural Poetics (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1999), the most important contribution to date to the understanding of this neglected group of modernists.

5. DuPlessis, “Inside the Middle of a Long Poem,” in Blue Studios: Poetry and Its Cultural Work (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006), 250.

6. Kathleen Fraser, “Translating the Unspeakable: Visual Poetics as Projected Through Olson’s ‘Field’ into Current Female Writing Practice,” in Translating the Unspeakable: Poetry and the Innovative Necessity (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2000), 175.

8. DuPlessis, Pitch: Drafts 77–95 (Cambridge: Salt, 2010).

9. DuPlessis, “Inside the Middle of a Long Poem,” 250.

10. Denise Levertov, “An Admonition,” in Poetics of the New American Poetry, ed. Donald Allen and Warren Tallman (New York: Grove Press, 1973), 310.

11. “Langdscape” is used throughout the oeuvre, see especially the opening to “Draft 68: Threshold” (66).

12. DuPlessis, “Inside the Middle of a Long Poem,” 237.

13. DuPlessis, “Working Notes for ‘Draft 71: Headlines with Spoils,’” How2 3, no. 2 (2007).

14. I wrote about “selvedge” in “Origami Foldits”; it is first used in Tabula Rosa as a poem title and picked up again throughout the oeuvre. See, for example, “Draft 21: Cardinals.”

15. DuPlessis, Drafts 1–38, Toll (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2001), 170–72.

16. “Conjunctions” and “Draft 27: Athwart,” in Drafts 3–14 (Elmwood, CT: Potes and Poets Press, 1991), 86 and Drafts 15–XXX, The Fold (Elmwood, CT: Potes and Poets Press, 1997), 68.

17. DuPlessis, Drafts 1–38, Toll, 170.

19. DuPlessis, “Otherhow,” in The Pink Guitar: Writing as Feminist Practice (London: Routledge, 1990), 149.

20. DuPlessis, “A Statement for Pores,” Pores: An Avant-Gardist Journal of Poetics Research (July 2002): 2.

21. See Jerome Rothenberg, Khurbn and Other Poems (New York: New Directions, 1983).

22. DuPlessis, Genders, Races, and Religious Cultures in Modern American Poetry, 1908–1934 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), chapter 6.

23. DuPlessis, “Draft 11: Schwa,” in Drafts 1–38, Toll, 79.

24. Tarlo, “Recycles: The Eco-Ethical Poetics of Found Text in Contemporary Poetry,” 120–21.

25. Perhaps it is also a reference to the tenth house in astrology, which is referred to in “Draft 67: Spirit Ditties” as a “darkened house, / memory house” (55). It is the house of the public sphere and of parental influence, hence perhaps the house of inheritance from our forbears.

26. See also the blood presented as “sweetened, crinkle-packaged, / bright-named something else” in “Draft 74: Wanderer,” 117.

27. DuPlessis, Drafts 39–57, Pledge (Cambridge: Salt, 2004), 168.

28. Henry David Thoreau, Wild Apples and Other Natural History Essays, University of Georgia Press, 2002.

29. Tarlo, “‘Origami Foldits’: Rachel Blau DuPlessis’s Drafts 1–38, Toll.”

30. DuPlessis, Drafts 1–38, Toll, 166.

31. DuPlessis, “Draft 47: Printed Matter,” in Drafts 39–57, Pledge, 77–87.

32. DuPlessis, “Draft X: Letters,” Drafts 1–38, Toll, 64.

33. See also “Justice demanded no more” in “Draft 74: Wanderer,” 120.

34. This is but an extract from a pretty comprehensive list to be found at DuPlessis, “A Statement for Pores.”

35. Again, as with the Objectivists, there is a critical counterpart here in her contemporaneous 2001 book, Genders, Races, and Religious Cultures in Modern American Poetry, 1908–1934. Here DuPlessis broadens her poetry criticism of the early Twentieth Century to consider wider issues of race and culture, in addition to gender. Having said that, I am conscious that I have marginalized discussion of gender in Torques in this piece somewhat. It remains a concern of course, but one most commonly discussed with reference to DuPlessis.

36. “‘Corpses of Poesy’: Some Modern Poets and Some Gender Ideologies of Lyric,” in Feminist Measures: Soundings in Poetry and Theory, ed. Lynn Keller and Cristanne Miller (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994), 85.

37. H.D., Trilogy (Manchester: Carcanet, 1973), 53.

38. DuPlessis, H.D.: The Career of That Struggle (Brighton, Sussex: Harvester Press, 1986), 113.

38. DuPlessis, H.D.: The Career of That Struggle, 91–92.

41. DuPlessis and Peter Quartermain, introduction to The Objectivist Nexus, 3.

42. DuPlessis, H.D.: The Career of That Struggle, 88.

43. DuPlessis, “A Statement for Pores.”

44. DuPlessis, “Inside the Middle of a Long Poem,” 241–42.

45. This piece can be found at UbuWeb.

46. See also “And work until it tolls” in “Draft 38: Georgics and Shadow,” Drafts 1–38, Toll, 267.

47. DuPlessis and Quartermain, introduction to The Objectivist Nexus,3.

48. Charles Reznikoff, Testimony: The United States (1885–1915), vols. 1–2, and Holocaust (Santa Barbara: Black Sparrow, 1978, 1975).

49. Anne Stevenson, “Charles Reznikoff in His Tradition,” in Charles Reznikoff: Man and Poet, ed. Milton Hindus (Orono, ME: National Poetry Foundation, 1984).

50. DuPlessis and Quartermain, introduction to The Objectivist Nexus,16.

51. Part of the next few paragraphs is drawn from “Recycles: the eco-ethical poetics of found text in contemporary poetry,” 123–25.

52. Richard Kerridge, “Climate Change and Contemporary Modernist Poetry,” in Poetry and Public Language, ed. Tony Lopez and Anthony Caleshu (Exeter: Shearsman Books, 2007), 132.

53. In Robert Hampson, “’Replace the Mindset’: Tony Lopez and the Turning of Public Language,” in Lopez and Caleshu, Poetry and Public Language, 102.

54. DuPlessis and Quartermain, introduction to The Objectivist Nexus,11. This is not a new term in her work, having been used in “For the Etruscans,” in The Pink Guitar: Writing as Feminist Practice, 2. In her later essay “Manifests” she writes of the danger that psychoanalysis should become a “near-mythic system of explanation” instead of a ‘social theory of interaction.” See Blue Studios, 206.

55. Lorine Niedecker, letter to Gail Roub, June 20, 1967, quoted in DuPlessis and Quartermain, introduction to The Objectivist Nexus, 12. See also Richard Caddel, “LN and Environment,” Lorine Niedecker: Woman and Poet, ed. Jenny Penberthy (National Poetry Foundation, Orono, Maine: University of Maine, 1996), 281-286.

On Rachel Blau DuPlessis

Edited by Patrick Pritchett