I think I understand Emma Bee Bernstein

I was thirty-three years old when Emma was born. I had been friends with her parents, Charles and Susan, for more than five years.

When Emma got to be about three or four we became friends in our own right. We simply liked each other a lot. I had never had children of my own / so that undoubtedly played some part. But the reality is that I felt some kind of kinship between us that went beyond any of the available clichés / even those of friendship.

When I would go to their apartment at 464 Amsterdam Avenue for a visit / perhaps prior to having dinner there / perhaps just to occupy and to enjoy a part of the afternoon / Emma would invariably (and as soon as it were possible (ok / before (before) it were really decently possible (socially speaking))) take my left hand in her right hand and lead me into her small bedroom.

And that (then) is what it was all about. Emma had her own space / but it was Emma’s space. Already / by the age of three / Emma had contrived a room of her own — and she may well have been conscious of having (done) that (of owning that) before she began showing it to me (I don’t know).

The walls were a matte white color / not at all bright / and there was room also for a small chest of three or four drawers. Already / in that tiny room / were all of those things that Emma would become (really (really) really become). From my first visit onwards the walls were covered with images cut from magazines. I don’t know where she got those pictures / but she got a lot of them. Most of them were of people — it didn’t seem to matter whether they were well known or not / but it was tacitly apparent that it certainly did (did (that it certainly did)) matter to Emma what they looked like / and what they were wearing / and (although their organization on the wall defied easy categorization) also (I think) how they went together. I have a sense of wildness / not only of the collage as a whole / but of the individual pieces of image that fed into that collage and came out of it as something else — the parts created the whole so that it could transform the parts / and in that way there was a unity of form and material that was unassailable. It was easy to tell that this organization of her most intimate physical space constituted a large portion of her confidence.

Emma’s confidence was her identity. I don’t mean to suggest / or to try to convince you / that that was all that there was to her — but I believe that it was that confidence that made all other aspects of her personality (all other aspects of what she was) cohere. And I will say that it was completely formed / and completely in evidence / from the time during which I first knew her.

The collage of images on the walls changed considerably from visit to visit — I can’t say in what way / I hadn’t trained myself to see that — but I could see that different parts of the space were covered / that some pieces of paper had been unstuck and others stuck. In this sense it would probably be more accurate to speak of a montage (the motion supplied by the viewer’s eyes / the looking) than of a collage — the latter term seems adequate to something that someone makes on a smallish piece of paper / but Emma’s project was so manifestly much larger than that. I couldn’t (for that matter) determine how such a small person had gotten those pictures all the way up toward the top of the walls — some seem in recollection to have been growing up from the walls and onto the ceiling / making of it the bottom of the fish tank one would be in when lying in bed. If we accept this suggestion that the considerable changes in lexicon over time made of the work more a montage than a collage / we can see the project as having been akin to the making of a film / but one (certainly) in which the people (the persons) were foregrounded as both actors (and / in that way / over time) as the actions also. People were the actions that occupied her mind / and the space beyond her mind that was also her mind.

It was hard not to see that space / more-or-less-white and more full of than cluttered with images / as the inside of the skull in which Emma lived (in which she had chosen to live / and which she had made to live within). So that she herself was the mind in the skull of her room (a room of her own). It is tempting to think what it might have been like for her to be in bed and to be going to sleep in that room / to be going to sleep inside the extensive precincts of her own mind — and where else? / where else indeed? / except that in her case that mind was so made to be seen (seen (so made to be seen)) / and except that in her case that mind was so made to be lived within. I doubt that Emma ever experienced the kind of tranquility before repose that I’ve suggested — she was far too active (always) for that / she was that always active mind. I doubt very much that she experienced the difference between dream and waking that gives the rest of us occasional pause — if your mind is always external to yourself / something that you live in (in (that you live in (in))) / then it doesn’t much matter what goes on in it as long as it is productive of the active generation and continuous regeneration of that space in which that mind has chosen to reside (in which that mind has chosen to live that life).

And / in the back on the right / pushed almost against the foot of the bed / and itself white (or once white) as well — the small chest of drawers. The home of Emma’s wardrobe / the exoskeleton of its being / that other (analogous) way in which the mind manifested the mind to itself. The fact that wardrobe-within-seeing-mind shared space with images-of-things (of people (people (of people))) seen also within (and spilling into) that space — here also was already the work that she would always make — people / in-clothing / in-space / seen (and pictured) in the seeing mind / as (as) mind (as mind seeing mind). What she saw she saw always face-to-face.

*

When her brother Felix got a little older I more than once settled down to a game of chess with him when I got there / but it never lasted beyond a few moves — Emma needed to have her world seen / and (perhaps) to have it be seen that her mind and her world were in no way (and in no part) separate (or separable). Again / the tugs on the hand / giving way quickly to laughter mixed with willing acquiescence — her mood was always impossible to refuse. How would you say no to someone who is saying to you — Come with me / I want to show you my mind / I love it / and I know you will too? How would you say no to an artist (who is saying all of that to you)? / especially with you yourself being some sort of one of them too?

*

Emma seemed most always to be a pure immanence of enthusiasm.

*

When Emma was perhaps nine or ten / my lover and I visited Charles and Susan / and Emma and Felix / where they had rented an upstate house for some part of their summer vacation. When we arrived Emma was playing part of the time in-and-around an inflatable wading pool. As soon as we had alighted from our car / before we had sat down in the yard with our hosts / midway through greetings — Emma took me by the hand and led me into the house (entirely strange to me) / and up to the second floor / to see the current version of where-she-lived. Here there were a few toys in place of the collaged walls / but for some reason (was there a reason?) the usual had to be repeated even though if in its present incarnation it couldn’t offer much more than the form of what we usually experienced. Perhaps to Emma it was the form of the occasion that mattered (most) / but somehow I don’t think that that’s quite it — it seems more likely to me that in the absence of the absolute-unity-of-form-with-content that this experience offered her at home (and me) / she would accept (in this instance) a formal reminder that that other experience was available (that it could (could (that it could)) be had / again).

Alan Davies in 1990, around the time he first met Emma Bee Bernstein (© Laurie Leber).

We stayed overnight / had a good dinner together / lots of friendship and talk. And after a great breakfast at the local diner (with its Ollie North T-shirts for sale) we left for home.

*

Charles has from-time-to-time-over-the-years reminded me of something that happened at a poetry reading that I gave at the Ear Inn. Emma was perhaps five or six at the time. After I had given my reading Emma turned to Charles and said — I think I understand Alan Davies.

She evidently said this in seeming earnestness / and it was doubtless in response to what I had just read. So it was a considered and a serious response.

Perhaps it offers (at least) a clue to our friendship / begun already a couple of years earlier. She did (did (she did)) understand me / and I did (did (I did)) understand her.

*

The last time I saw Emma was at a Segue reading at the Bowery Poetry Club in the winter of 2008. I was co-curating the series for a couple of months / and standing in the back of the room / when Charles approached me and said — There’s Emma … with some of her friends … Why don’t you go and say hi to her? — at the same time pointing out the several people sitting around a table near the stage. I felt under just enough additional pressure with needing to make sure the reading went moderately smoothly / that I didn’t take his suggestion. While introducing one of the two readers / I saw Emma sitting quietly with her friends / and had time only to note that she looked as though she were charged-with-energy / while at the same time I saw that there was darkness around her eyes.

*

It is usually the birth of a child that begins to put parents-who-so-choose in the role of the stage mother and/or the stage father. In this case / the opposite of that has happened — it is the death of Emma that has motivated Charles and Susan to do everything within their power to promote the artistic works that Emma produced within her relatively short life.

*

I don’t remember (the adolescent) Emma ever being still / at rest. Normally we think of even a moving object as moving between two points / at each of which there is some form of stillness — we know that the perpetual motion machine is a fancy and not a reality / we’ve been taught to expect even the-universe-as-a-whole to slow down. Counter that / we’re told that children are the greatest athletes / and with that comes the expectation of at least considerable (considerable) motion. But Emma never (never) stopped — I never saw her not-moving.

Here there is a realization that contains the kernel of a contradiction — the still photographer slows down completely (completely) what it is she captures (captures) on her film / and even objects in motion (Muybridge) are stilled so that they can be apprehended (apprehended) as such. This plausibly-unexpected shift in Emma’s being (in Emma’s being Emma to Emma) is punctuated by the fact that for a good many of her photographs it was she who sat (who “sat”) for herself.

*

A collage or a montage would differ from other kinds of sensible statement in the sense that (or in the extent to which) it is composed of pieces that have been intentionally (and intently) prefigured for that purpose. In this way it would resemble (it might most resemble) those of the plastic arts the making of which is preceded by the making of the-materials-of-which. Most artists work with materials which they bring to hand for that purpose / but they do not for the most part actually make those individual things which are then to be the materials of their constructions — Emma’s constructions made it seem that she did.

It seems probable to me that having this as the origin of her senses of the ways of making things / would then influence Emma in the way that she went about making her photographs. And it is certain that this way of prefiguring her most immediate world about her (the room where she lived (as a child)) would then devolve into her ways of presenting her photographs to the world — in such a way that the photographs become the elements of the collage/montage / and a wall is found (somewhere) for their mingling and elucidation.

Emma Bee Bernstein, Senior thesis show, installation shot, University of Chicago, June 2007.

*

We all have ways of externalizing what we are where we live. We bring home to our own hole in the coral those things that make us feel at (at (that make us feel at)) home. For me those things are mostly books and CDs and clothing. For most of us they are objects that we get elsewhere and transport to where we live. This is an indication of the extent to which we are not bounded by our bodies / the extent to which we not only live but are (are (not only live but are)) beyond our constantly-changing skin.

What has been unique in Emma’s case is not only the extent to which she was aware of this as a child / not only the extent to which as a child she participated in this externalization-of-self (this externalization as (as) self) — but the fact that her choice of imagery-as-extension-of-self prefigured her career as an artist. The images were images of humans / and in this way too we could already see the intensity of vision (of self (self) of self-vision) / of self-visioning / that marked her attention to the emotional details of her life. This particular sort of externalization is reflective — it shows the visioner seeing back at herself (as a self / as a choice of selves) / and that too is unique — the self that is externalized (as living (living) as living-place (space)) is the self looking back (in guises) at the self that is externalizing itself / there / where it (most) lives.

*

Now / Emma is not here.

At times like these it is by managing our grief that we live. Otherwise.

Is it worth mentioning that / at-times-like-these / are endless?

* * *

The notes that follow were made with specific reference to a show of Emma Bee Bernstein’s portraits / at the Janet Kurnatowski gallery / in Greenpoint / in the spring of 2011 / curated by Phong Bui and Linnea Kniaz.

The photographs were not titled by Emma. Titles were added by her family / for the purpose of identification.

I’m getting really fond of the room in spite of the wall-paper. Perhaps because of the wall-paper.

— Charlotte Perkins Gilman, The Yellow Wallpaper (1899)

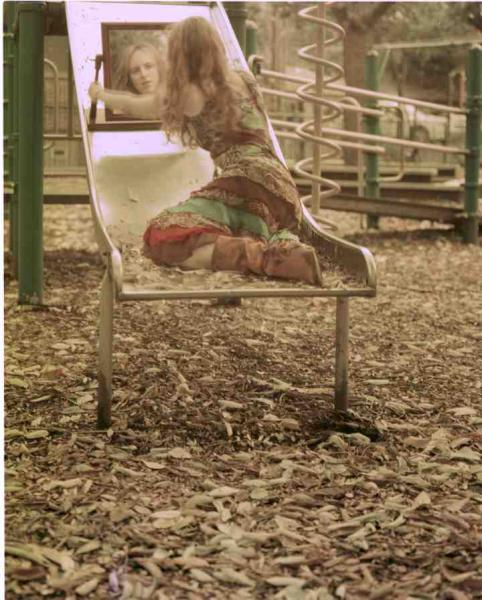

Emma photographed herself and friends of her own age / women in their early twenties. The women are not smiling — this does not mean that the atmosphere is one of dour contemplation — but something is being asserted that is staid and solid — it is that they are who they are / that that is that / and that nothing will change that (except change-itself?). Most of the photographs are frontal / some showing the subject in a landscape or room / some from the waist up (none closer). The subject is always alone — even when the portrait is of two women / they are alone. [ at right: Self-portrait with yellow wall (2007)]

Emma photographed herself and friends of her own age / women in their early twenties. The women are not smiling — this does not mean that the atmosphere is one of dour contemplation — but something is being asserted that is staid and solid — it is that they are who they are / that that is that / and that nothing will change that (except change-itself?). Most of the photographs are frontal / some showing the subject in a landscape or room / some from the waist up (none closer). The subject is always alone — even when the portrait is of two women / they are alone. [ at right: Self-portrait with yellow wall (2007)]

Except for you (of course) / you the viewer.

Are you / then / the subject?

Frequently the costume of the subject (a dress or a nightgown) blends in (in some marked deliberate way) with the background. In “Self-portrait with yellow wall” Emma wears a dress with a paisley print that features yellow — even the cigarette hanging from her hand has been made yellow by the preponderance of yellow light — her golden shoes reflect yellow. Emma herself is backed into a vibrant yellow corner.

(from left): Jill against the brown door (2006), Marianna and floral wallpaper (2006), and Antonia in clown suit (2006).

Flowered dresses frequently find themselves in a-yard-of-flowers. Marianna wears a flowered gown against flowered wallpaper. Jill wears brown when photographed against a brown door. Antonia wears a blue clown suit (which manages to look not-at-all-clownish) in a blue room. Anat wears a dress with autumnal colors / when seen against a groundscape of fallen leaves / and a background that also somehow contrives to be largely brown.

This kind of placement makes a number of statements. The figure is a figure in a ground of which it is naturally (if not exactly seamlessly) a part. The figure is as-if-produced-by-the-ground against which it is seen. In nature / this kind of coloring-matching-its-surroundings is known as camouflage — and that is (in part) what it has to be seen as here — the women / while posing / to be photographed / are at-the-same-time hiding (they are blending in) — and this structure (a motif) is a contrivance of the photographer herself / of Emma. [at left: Anat, Autumn reflection (2006)]

This kind of placement makes a number of statements. The figure is a figure in a ground of which it is naturally (if not exactly seamlessly) a part. The figure is as-if-produced-by-the-ground against which it is seen. In nature / this kind of coloring-matching-its-surroundings is known as camouflage — and that is (in part) what it has to be seen as here — the women / while posing / to be photographed / are at-the-same-time hiding (they are blending in) — and this structure (a motif) is a contrivance of the photographer herself / of Emma. [at left: Anat, Autumn reflection (2006)]

There is a striking photograph entitled “Self-portrait in red rose dress in green garden” / in which Emma becomes a red blossom among blossoming plants.

Self-portrait in red rose dress in green garden (2007)

The general mood is staid / a mood that sometimes verges on the solemn. No one told these subjects to “Say cheese.” They are addressing us / where we are. Where are we?

The fact that some of the women are photographed wearing nightgowns or bathrobes lends a momentary instance-of-the-casual to what is being photographed / to what-is-being-shown. But this is deceptive — none of the photographs appear to have been taken impromptu / everyone is busy being very-much-who-they-are (who-they-are-seen-to-be (who-they-are-made-to-be-seen-to-be)). This means that each instance of each individual is an instance of integrity (of meaning-meaning-itself).

What we choose to put with what / is a statement about who we are. Emma knew this / as she placed her friends in land- and room-scapes that she knew would help define them.

Those photographed do not (in this sense) stand out — they are very much a-part-of-the-photographic-rectangle / they do not stand out from it — the plane is relatively flat. In this / the photographs resemble snapshots / a-thing-taken-on-the-run.

But this lives in-a-kind-of-tension with the certainty we have that each photo has been posed.

What does it mean that the photographic images have been staged / contrived / that they are not in-that-sense candid? Candor is what we look for from another person / one of those things we most value in someone. But here what-is-candid is not the photograph-as-object — what stands in (instead) for candor / is the solidity of the subjects / their outward-staring-look / and the feeling that it-is-that which they are about-to-speak (such that it is that about-to (about-to) that is candid / in these instances).

There is a kind of sadness about the-stillness-of-the-perceptions / the-women-perceiving-out-to-the-photographer / the-view-(and-the-viewer)-perceiving-in-to-the-women. The looker-at-a-wall-mounted-photograph stands (roughly) in-the-space-the-photographer-inhabited — in that way / the view (the viewer) obliterates the photographer / makes her be out-of-the-way / so that the-view-(the-viewer)-can-essay-(assay)-the-view. This is particularly-the-case when the subject of the photograph is a (another) human subject / on some levels an equal to the viewer. So that then there are three of us — the photographer most absent / because not seen (not-there) — the subject of the photograph / absent as-living-body / but still seen — and the viewer / present / but absent insofar as not being a part of that permanent-instance-of-the-once-photographed. Is anything really there / after all?

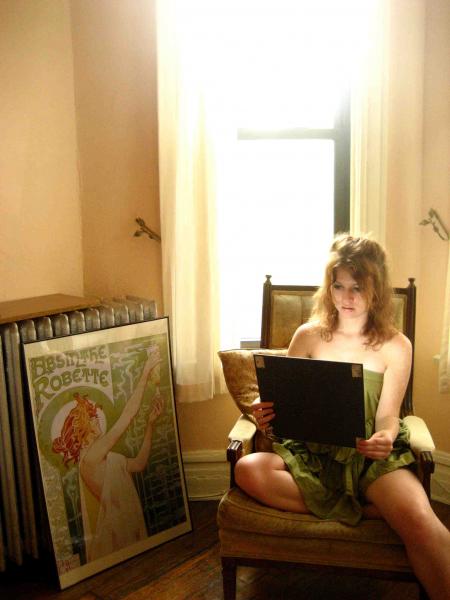

This kind of mirroring / is mirrored in some of the photos. “Jill with Art Nouveau print and mirror” [(2007), shown at right] shows Jill in an easy chair / wrapped in a green towel / with a mirror on her lap (she is looking at it) / and with an Art Nouveau poster wrapped in plastic occupying-the-lower-left-part-of-the-frame — there is a-window-streaming-full-of-light behind-and-above her. The poster is of a young woman / which Jill then mirrors — at the same time we know that she is undergoing-a-kind-of-mirroring in the open lens (that word leaps-to-mind) of the mirror into which she gazes. Where / in this instance / are we? — in a more uncommon relationship to the photograph than otherwise / not only because of the presence of the mirror / but because it is a source of light / and (in-that-way) can be seen to see / because light is the-substance-of-seeing (it makes seeing possible — it makes the-taking-of-photographs possible — it mediates between us (the viewer) and the-thing-seen (in this case a photograph (its subject seen because of-light — the-taking-of-it made possible by light — the viewing of it likewise))).

This kind of mirroring / is mirrored in some of the photos. “Jill with Art Nouveau print and mirror” [(2007), shown at right] shows Jill in an easy chair / wrapped in a green towel / with a mirror on her lap (she is looking at it) / and with an Art Nouveau poster wrapped in plastic occupying-the-lower-left-part-of-the-frame — there is a-window-streaming-full-of-light behind-and-above her. The poster is of a young woman / which Jill then mirrors — at the same time we know that she is undergoing-a-kind-of-mirroring in the open lens (that word leaps-to-mind) of the mirror into which she gazes. Where / in this instance / are we? — in a more uncommon relationship to the photograph than otherwise / not only because of the presence of the mirror / but because it is a source of light / and (in-that-way) can be seen to see / because light is the-substance-of-seeing (it makes seeing possible — it makes the-taking-of-photographs possible — it mediates between us (the viewer) and the-thing-seen (in this case a photograph (its subject seen because of-light — the-taking-of-it made possible by light — the viewing of it likewise))).

There are mirrors in other of the photographs. It is hard to say which mimics which / the mirror the photograph? / or the photograph the mirror? I suppose the answer to that question inevitably takes us into the realm of narrative. [We might mention the book Girldrive / co-made with her friend Nona Willis Aronowitz / and for which Emma made photographs of many women. The book is about young feminism.]

There is a photograph taken by a window (a-kind-of-absent-(or-potential)-mirror) [at left: Jill with glass (2006)].

There is a photograph taken by a window (a-kind-of-absent-(or-potential)-mirror) [at left: Jill with glass (2006)].

And there is a photograph / “Gabi and Antonia on couch” / in which a large heavily-framed painted portrait (wall-hung) divides the two sitters / each of whom leans-away-from the painting in-a-different-direction / so that the painting separates them / while (at-the-same-time) the two brown-haired-women wear identical nightgowns / and share the same posture although in-mirror-image. It is interesting that the-top-half-or-so-of-the-painting is not included in the photograph / but there is still enough (just-enough) to let us know that it is a painting of a person. The women’s clothing and their posture twins the two sitters — the painting separates them / holding them apart. Is this a statement about the meaning (the function) of art? If it is / it says that in-some-way art divides the person / but that in-doing-so it still leaves her intact as divided instance of that-one-self. Perhaps art splits us off from our self / while (at-the-same-time) bringing us face to face with (with (face to face with)) that-self — but the question then remains / is the-self-to-which-it-returns-us the whole self (before the confrontation of the-work-of-art) / or the divided self (after that confrontation)?

Gabi and Antonia on couch (2006).

Emma also made some strained self-portraits / all featuring partial nudity. In one Emma reclines in a contorted posture — she has just added the fourth lipsticked-kiss to her own leg / which has been bent toward her mouth — but these kisses look like nothing-so-much-as-wounds.

Self-portrait licking knee (2006-2007).

In one / lying down on the floor / Emma has written I WANT U across the lower part of her naked ribcage — her posture / and the-look-on-her-face / says that-isn’t-so. And in another / also lying-down-on-the-floor / the word HUSBAND has been written on a piece of paper that hides her breasts — she has a cigarette in her mouth. In both of these photographs her skirt has been pushed up / exposing part of her pantied crotch above knee-high-socks — the sign feels like a weight / an insolent burden.

These photographs / and there are others that are not-unlike-them / resonate with the one called “Self-portrait crouching with plaster wall.” Emma crouches / her bodice is partly exposed to the viewer / as are her black-nylon-clad legs / she has a long cigarillo between her lips / and her arms are bent behind her back. We are looking down on her — she is looking up to (?) / at / us. It is the classic posture of the submissive — further / it is a photograph of a  submissive who does not speak (because-of / and signified-by / the cigarillo-between-her-lips). She looks up / mascara or other makeup lending a look of fear to her demeanor — a red band binds her hair. Reaching out from-each-side-of-her-head there are patches of wall-damage that look like either the molting antlers of an elk or moose / or the frayed wings of an angel. [at right: Self-portrait crouching with plaster wall (2006)]

submissive who does not speak (because-of / and signified-by / the cigarillo-between-her-lips). She looks up / mascara or other makeup lending a look of fear to her demeanor — a red band binds her hair. Reaching out from-each-side-of-her-head there are patches of wall-damage that look like either the molting antlers of an elk or moose / or the frayed wings of an angel. [at right: Self-portrait crouching with plaster wall (2006)]

In a way / the desperation expressed in these particular photographs makes them the most hopeful. In the feminist context that Emma espoused (in the way that she lived / in the things that she made) / they represent that point of rupture with what-is-otherwise-culturally-acceptable / but what to Emma was so manifestly unacceptable — they enact a scream (of rage / not terror) / and out-of-that-scream (if anything exact can be articulated there) / the word NO!

In the overall context of Emma’s work / the photographs of two-women-shown-together are reassuring — and the fact that the photographs which are not self-portraits are of her friends / reminds us that friendship is to be valued / that it stands for something-in-this-world (regardless the social and psychological ambience).

The rawness of some of the self-portraits is also offset by (balanced-by) such a photograph as “Self-portrait in pink bathrobe” / where her right arm resting-on-a-rod-holding-pure-white-fringed-towels becomes the wing of an angel / about to take flight.

from left: Self-portrait in pink bathroom (2006), Marianna with chandelier (2006).

Or / “Marianna with chandelier” shows the subject looking-up-at and reaching-toward a bright chandelier that takes up slightly more than the top half of the photo — clearly (and I mean that literally) / she is about to transcend (if not to ascend) / and the-fact-that-she-is-about-to-transcend is made more manifest by the fact that-we-know-not-from-what(-from-what).

The photographs leave me feeling taken-aback — backed into the wall behind me / which I am not aware of as-image / but that never-the-less prevents me from being other-than-where-I-am (e.g. (alternatively) out-there).

Five people have entered the gallery — they’re moving slowly about / and talking — but it is the young women in the photographs on the-gallery-walls that are alive (alive (that are alive)).

Why is this?

It is because they have come here to be (and to-remain) who-they-are. While those few people in the gallery (myself included) are temporary phenomena (at most)

And what does it mean / later / now / that these photographs / that these women / are all-together (in-this-room)? It is a kind of litany really / a statement about friendship that is slow-and-steadied / numerous instances of that one thing (a-young-woman’s-way-of-looking-(of-appearing)-when-being- in-the-world).

The photographs / in-the-room / communicate with-one-another. The subjects / the young women / look outward / at us / and do not communicate (with-each-other) — but (still) there is perhaps something being whispered from-photo-to-photo / and that something has-something-to-do-with-the-meaning-of-life / with why we value it / with what it might (it might) be for.

Seeing the photographs grouped on the walls / the relative strength or weakness of the figure relative to (with) the ground / varies. These variations represent (they stand-in-for) the range of emotions that the women are being said to feel — and / the range of their-relative-nearness-to-or-distance-from-the-world. It is not that they (the women) are in-or-out-of-focus — it is (rather) they that are focusing (they are the-focusing) / and (in-this- way) they focus us (in-and-relative-to-that-world (their-world) and (as conscious viewers) to our-own-world (the one we inhabit / as viewers / viewing)).

The focal point of Emma’s camera is a woman’s face. Her body. Her being.

Photographer / photographed — face to face.

9Feb10 / 25Apr11