I to eye

Self and society in the poetry of Lawrence Joseph

For most of his career as a writer, Lawrence Joseph has stood outside the prevailing schools of poetry, but his uniqueness has been hard-won, and is the product of his evolution as a poet. Reading his four books of poems chronologically reveals not just the important continuities — his concern with identity, religion, language, and politics — but the important changes, all of which will come to define his exceptional place among his contemporaries. Hardly a static poet with a closed system of ideas and imagery, Joseph emerges over time as a poet with a clear sense of the world outside himself. In short, his poems begin with a hypersense of the self, expressed in numerous poems with the poet (the “I” of most of the early poems) at the center. But, as even a cursory reading of Joseph’s later books shows, the “I” has almost disappeared, replaced in effect by what Joseph calls in one poem (the title of which lends itself to the title of this Symposium): “the transparent eye.”[1] That poem also provides a template of sorts for Joseph’s entire work, against which we can measure his shifts in voice and vision: “Some sort of chronicler I am, mixing / emotional perceptions and digressions, // choler, melancholy, a sanguine view. / Through a transparent eye, the need, sometimes, // to see everything simultaneously / — strange need to confront everyone // with equal respect.” The poet makes clear that his vision is democratic, looking up and down society with respect for all. And he wants to see it all at once: a synchronicity of experience that encompasses both the street and skyscraper. He will accomplish all this with many emotional responses and plenty of pertinent digressions, and we can expect little humor or exuberance, but lots of somber, sober thought. As he tells us in an earlier poem, “Not Yet,” in words reminiscent of Saul Bellow’s Augie March, himself another urban ethnic: “I want it all” (21).

The move in Joseph’s poetry from a highly subjective self to a greater objective eye in a way relies on the intensely personal early work. Joseph could not evolve into the sophisticated observer of the later work without this outburst of emotional expression in the early work. In Shouting at No One (1983), Joseph establishes the contours of his history, which will surface in later poems, but there only obliquely, and not always identifiable as personal history. Joseph discovers himself as a young ethnic Catholic in Detroit, only to push those facts into the background in his later work. The first book reads therefore very much as a first book. In poem after poem, Joseph appeals to the reader’s sense of authenticity — he wants us to know his story, and his family’s story, and the story of his city. The surest sign of this is his reliance on an abundance of local detail. Beaufail Street, Fort Street, Van Dyke Avenue, Mt. Elliott Street, Boston Boulevard, Vernor Highway, Dix Highway, Mack Avenue, Bellevue Street — the list of streets named in this volume goes on, all of them, one assumes, in Detroit, “a city that moans in its dirt” (“Even the Idiot Makes Deals,” 59). Joseph doesn’t limit himself to street signs, but includes local places of business, with their strange, colorful, and evocative names, like Resurrection Lounge, Eastern Market, Buck’s Eat Place, Eldon Axle — suggesting, in short order, the religious, ethnic, and class makeup of his Detroit. And let us not ignore the churches: Saint Anne’s, Saint Maron’s Cathedral, Our Lady of Redemption Melchite Catholic Church, Our Lady of Lourdes, and Saint John Nepomocene — one of which invokes the unusual Catholicism of Joseph’s ancestors, the Maronite Catholics of the Near East. So far, welcome to Joseph’s Detroit: the Motor City, the land of Dodge Truck and the Whole Truth Mission, of Henry Ford and Marvin Gaye, and perhaps most of all, Joseph’s Market.

At the center of Joseph’s early work is family myth — not, mind you, myth in the sense of not being true, but in the notion that these narrative details will provide a foundational story, aspects of which Joseph will refer to time and again. His family-owned store figures in many of the early poems, as does the primal scenes of his father’s shooting and the 1967 Detroit riots. The first poem of his first book, “Then,” set during the riots, not only narrates this key moment in Joseph’s past, but makes clear its significance: “it would take nine years / before you’d realize the voice howling in you / was born then” (8). The anger and despair which characterize so many of the early poems were also born at the moment, as was Joseph’s sense of himself as both avenging angel and “the poet of heaven” (3).[2] The poem “Not Yet” further emphasizes this fundamental truth of Joseph’s early work. Contemplating his father breathing unevenly, the poet confronts his anger and vows to speak out: “I don’t want / the angel inside me, sword in hand, / to be silent” (21–22). This scene plays itself out again when his uncle, also working at Joseph’s Market, recalls his near-fatal stabbing during a robbery (59). The poet eventually reaches further back in family lore — to Lebanon, most of all, in the longer poem, “The Phoenix Has Come To A Mountain In Lebanon,” a poem in which the “I” does not speak for the poet. Instead, nameless peasants speak of the promise of America (“another world”) where money can be made in factories (29). It is a generalized account of the great Diaspora — the source of so many new Americans, including the poet’s grandparents and Khatchig Gaboudabian, the Turkish immigrant to Detroit whose story lends itself to one of Joseph’s longer poems not about himself or his family.[3]

Though family history plays an important part in Joseph’s early poems, he also focuses on the emigrants’ place of arrival: Detroit, a city desperate for salvation: “Who will save / Detroit now?” the poem “Fog” asks (33). And it is clear that Joseph considers himself a poet of that city. Contemplating the murdered Thigpen in “I Think About Thigpen Again,” the poet recognizes a kindred spirit — a fledgling poet in Thigpen’s case, who writes about the ugly side of Detroit life. “He would,” we are told, “be the poet of this hell” (16). To be sure, plenty of other Detroiters exist in Joseph’s early poems, but they are mostly described in a line or two, and often come from the street life he sees all around him: junkies, drunks, gang members, a mad woman. And lest any readers doubt Joseph’s own credibility as a singer of his city, he mentions a number of his own and others’ work experiences in typical Detroit jobs — at Hudson Motorcar in “Nothing and No One and Nowhere To Go,” “over [a] machine” in “In The Tenth Year of War” (51), and at Dodge Truck in “I Had No More To Say,” where Joseph “swung differentials, / greased bearings, / lifted hubs to axle casings / in 110° heat” (11). Detroit determines most of the imagery throughout the poems as well — the yellow smoke, the pig iron, the press machines, the giant magnets looming over the cityscape.

The poem which best sums up the first book is “There Is a God Who Hates Us So Much.” All of Joseph’s early concerns come together in this five-part, intensely subjective work: the matter of Detroit, Joseph’s identity as a poet, his Catholicism, and his family’s history. In the first lines of the poem, we come to understand the full meaning of the announcement in the book’s prologue that the “you” who “will be pulled from a womb / into a city” (3) is the poet, and that the city is Detroit: “I was pulled from the womb / into this city” (46), Joseph proclaims, and further asserts later in the poem that he is in fact “the poet of my city” (48). This city of burning air, bloody and greasy hands, and scary streets is “the shadow / strapped” to his back; he is also “the poet of that shadow.” From his parents the poet has learned about silence, sadness, and violence. The final quatrains set the overwhelming question for the early work: how can God allow all this — the city in flames, a father shot? In words that echo that other poet of Detroit, Marvin Gaye, the city “makes [him] want to holler” (50). And why not? He has done his time on his knees, kissed statues, held holy candles and palm branches, received communion, and prayed to emulate the saints. Clearly, as he says twice, “There is a God who hates us so much.” In another sense, he also identifies, perhaps unintentionally, his limits so far as poet: amidst the sounds of his city, he “could not abstract” (47).

In other words, Joseph in his first book filters the world — a world mostly confined to family and Detroit — largely through himself; he does not “abstract,” or perceive things objectively because he feels everything so intensely and personally. He does not deny but is angry with God, as many of the later poems in the book suggest. The poet acknowledges his transgressions — sexual thoughts mainly, but lies also — and comes to a final realization in the poem that gives the volume its title: it is not just the speaker “shouting at no one,” but, more significantly, “it’s God / roaring inside me, afraid / to be alone” (60).

Joseph’s second volume, Curriculum Vitae (1988), collected in Codes, continues with many of the concerns in Shouting at No One, still relying on his personal story as an ethnic Catholic in Detroit who has seen his share of working-class life. But Joseph also advances his larger design, becoming in the poems more self-conscious about his own identity, and coming closer to that democratic ideal articulated in “Some Sort of Chronicler I Am” — a poet who surveys mankind from the factory floor to the boardroom.

So once again we find ourselves on the streets of Detroit — Dexter, Linwood, Brush, and the rest. And a new church is added to the list: the Shrine of the Little Flower. “There I Am Again” reminds us of the foundational story and its pull on the poet. No matter how hard he tries, he is still “in Joseph’s Market […] / […] always, everywhere, // […] the grocer’s son / angry, ashamed, and proud as the poor with whom he deals” (121). This poem concludes the volume, after Joseph has narrated more tales of his native city. “Factory Rat,” for one, speaks to his credibility as a worker, and other poems mention his brushes with famous Detroiters: “the largest independent” bookmaker in America (“This Much Was Mine,” 79) and the notorious Father Coughlin (“This Is How It Happens”). For the first, the poet caddies, for the other he serves as an altar boy.

At the same time, Joseph explores the deeper meanings of his ethnic heritage in poems such as “Rubaiyat,” “In the Beginning Was Lebanon” — the title here speaks for itself — and, most famously, in “Sand Nigger,” a brilliant collage of Eastern and urban images narrated by “a Levantine nigger / in the city on the strait” (92). Again, Joseph underlines the significance of Lebanon for his history; quite simply, “Lebanon is everywhere / in the house” (90). The immigrant family still figures in his work, though one could not characterize poems such as “My Eyes Are Black as Hers,” “Mama Remembers,” or “My Grandma Weighed Almost Nothing” — poems that face the very brutal realities of hard years with little money, miscarriages, a legless patriarch, and death by cancer — as nostalgic.

Joseph also moves beyond Detroit in Curriculum Vitae, in part to establish the authenticity of his experiences first, as a student overseas (“Stop Me If I’ve Told You” and “London”); then, as a law student (“An Awful Lot Was Happening”); and, finally, in a number of poems, as a lawyer in Manhattan. The poems set in New York best articulate Joseph’s desire and need to see society vertically. The demands of work “[i]n the offices of the great firm” (76–77) bring with them a crisis of sorts — not just the poet’s sense of not belonging, but also the constant contrast between the dizzying world of big money and the scuzzy reality of the street. In true Joseph fashion, we are very often in the street, and by name, whether Barrow or Hudson, Broad or Wall. A fancy meal in “I’ve Already Said More Than I Should” summons a memory of his grandmother walking with canes. After contemplating “the transfer of 2,675,000,000 dollars / by tender offer,” the poet thinks “about third cousins in the Shouf” (97). “I Pay the Price” suggests the moral economy at work for the young lawyer: He listens to “market analysts” as well as an incontinent madman lying on the sidewalk as he has to “distance” himself to see himself as someone “protecting interests” (106). From his apartment with a “good view” of the Brooklyn Bridge, he ponders a worker with a bandaged hand and thinks to himself: “I live in words and off my flesh / in order to pay the price” (105–106).

And what is the price? The poem “Any and All,” one of the strongest in the volume, best answers the question, moving up and down with rhythmic certainty while veering inward with a calm clarity. The drama also is vivid: the phone rings and the memory of a blind woman on the street vanishes as he is summoned to a partner’s office:

The lawyers from Mars and the bankers

from Switzerland have arrived to close the deal,

the money in their heads articulated

to the debt of the state of Bolivia. (113)

The language of law, the poem suggests — with its silly obsessions about the use of “any” or “all” — is in fact Martian talk to the rest of us. And the amounts of money at stake can be breathtaking, because, as he asserts a little later, Wall Street is the “emblematic reality of extreme / speculations and final effects” (113). The street-level scenes continue to draw his attention in the poem, but so do the anxieties of the workplace, where he cannot afford to laugh or identify with the blue bloods.

As much as Curriculum Vitae rehearses the matters of Lebanon and Detroit, as well as the poet’s ongoing sense of his Catholicism, it also represents the first serious engagement with a more aestheticized sense of the self. The epigraph from Wallace Stevens speaks to this concern, suggesting the notion that “in nature and in metaphor identity is the vanishing-point of resemblance” (63). And what does it mean in the first poem of the book, “In the Age of Postcapitalism,” that “the question ‘What Has Become of / the Question of “I”’” is discussed “at the Institute for Political Economy” (65)? Though Joseph asks that we abstract the “I” of the poems, it doesn’t seem to happen, for example, in the title poem, a succinct outline of the contours of his life: Beirut ancestors, Detroit birth, Catholic childhood, burgeoning sexuality, study abroad, the law. And the poet punctuates this litany with the language of authenticity: he “walked;” he “talked;” he “witnessed.” He wants us to believe he remains “many different people” but, for all intents and purposes, he’s still the Lawrence Joseph of “Let Us Pray,” not “Myself / an abstraction” of “Stop Me If I’ve Told You” (86, 87).

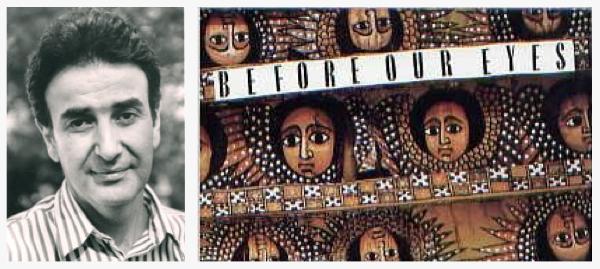

The concern with a subjective self in Curriculum Vitae comes to the fore in Joseph’s next volume, Before Our Eyes (1993, reprinted in Codes), a pivotal work that moves away from obsessive personal history into poems of greater length, longer lines, and more abstract thinking. The title poem (which is also the first poem) of Before Our Eyes functions as a kind of ars poetica:

[…] The point is to bring

depths to the surface, to elevate

sensuous experience into speech

and the social contract. (125)

The poet declares his work will be “a morality of seeing,” for which he might be dismissed. But the aim is true: to transform what he sees and feels into language, and, then, provide the greater contexts within the world outside himself, “the social contract.” He runs through some images familiar from his own history, wondering “don’t street smarts / matter?” (126). But ends with more aesthetic concerns: “The pure metaphoric / rush through with senses” probably “best kept to oneself.” For the length of this book, Joseph suggests “let’s just keep to what’s before our eyes.” The payoff is substantial in Before Our Eyes because Joseph makes his strongest statement of his artistic credo, and it is connected to his quest for an authentic self. Rather, he observes the world with a subdued spirit and, as noted above, with a “transparent eye.”

The poet declares his work will be “a morality of seeing,” for which he might be dismissed. But the aim is true: to transform what he sees and feels into language, and, then, provide the greater contexts within the world outside himself, “the social contract.” He runs through some images familiar from his own history, wondering “don’t street smarts / matter?” (126). But ends with more aesthetic concerns: “The pure metaphoric / rush through with senses” probably “best kept to oneself.” For the length of this book, Joseph suggests “let’s just keep to what’s before our eyes.” The payoff is substantial in Before Our Eyes because Joseph makes his strongest statement of his artistic credo, and it is connected to his quest for an authentic self. Rather, he observes the world with a subdued spirit and, as noted above, with a “transparent eye.”

The most Detroit-centric poem in this volume is called, interestingly enough, “Sentimental Education,” as if the poet were dismissing such a memory-laden narrative. Interesting also is that the poet is not all that much present in the poem, returning to Detroit “because you want to” (147). Moreover, the education of the title refers to what the city can teach — about Henry Ford and Marvin Gaye, but not as personal icons, as in early poems, but as parts of history. The poet refers to his “baptism by fire” in Detroit, but there is also a pervasive sense of farewell to all that (146). And in many ways, the rest of the book confirms it: the matter at hand is now Manhattan, and the poems authenticate the fact with the Joseph touch: he walks, among others, Horatio Street, Cornelia Street, Water Street, Grove Street, St. Luke’s Place and so on. “Material Facts,” as its title suggests, is all about observing the facts of the city and hearing its voices, with one telling interruption: “Myself, / self-made, separated from myself, / who cares?” (128). The poet displays here and in the following poem in the volume a sense of exhaustion with his previous self. In “Admissions Against Interest,” he asserts:

Mind you, though, my primary rule:

never use the word “I” unless you have to,

but sell it cheaply to survive. (131)

The poem also reminds us that “[a] lot of substance / chooses you” and that the poet would be lost with out his “Double” (132) Less concerned with his quest for an authentic self, he notices again that “the times demanded figuring out” and that “now I’m seeing / words are talk and words themselves // forms of feeling” (133–34). Other poems in Before Our Eyes demonstrate very objective, “I”-less content, still others record voices overheard. To take just one example, “Time Will Tell If So” opens with another summary statement characteristic of this later work:

A time of comedy sprung

to the eye, a sensational

time of substance and of form,

iridescent existences,

and the same old lowlife. (141)

Here the street-level scene is abstracted, and the poet indulges an outburst of humor. One notices that “Time Will Tell If So” appears after “About This,” which asks, “Where’s my sense of humor?” Certainly not in “About This,” with its chilling vision of war:

[…] This is wartime

bound to be, the social and money value

of human beings in this Republic clear

as can be in air gone pink and translucent

with high-flying clouds and white heat. (143)

War and rumors of war surface throughout the volume, as do the poet’s insights into the economic forces that shape our world, all part of the “social contract” and the “material facts” that now occupy the poet’s imagination. His self, or “I,” is diminished and abstracted — something he had a hard time achieving in the previous volumes. Joseph confronts new challenges as a poet. His “I” becomes an “eye,” surveying the world transparently, and democratically, while also coping with the limits of language, and the possibilities of silence he so willfully ignores in the early poems.

From the vantage of New York City, Joseph moves beyond cities to the subject of America itself, the course of empire, the power of money, “Atomic Age America,” the “phantasmagorical United States” (from “Generation,” a poem after Akhmatova). “Variations on Variations on a Theme” alerts us to Joseph’s new terrain — he is in “Walt Whitman’s country” (155). Although Wallace Stevens and William Carlos Williams purportedly account for many of Joseph’s ideas on language, he is more genuinely an heir of Whitman, whose democratic ideal in poetry he fundamentally shares. Whitman, after all, eulogizes presidents and battle wounded; he sings the country complete, high and low, with imagery taken from the streets he walked and the people with whom he talked. In this poem, Joseph at his Whitmanian best, begins at the top — a banker murmurs “the socialization of money has become / an abstract force” (154). Meanwhile, a street-dweller insists to anyone who will listen, that she has an advanced degree. A priest shares his thoughts about the survival of the species; a juror screams that a defendant is the devil; the poet overhears “a voice / on the Avenue sensuous enough to touch” (155). All of this while a war has begun, and a horrible image almost earns a smile:

— the eyewitness account the vanquished

appeared as if from a mirage of hot

oily smoke in search of someone

to surrender to — (156)

The poem ends with the arresting idea that “transparency can be painted,” an interesting comment on the emerging “transparent eye.”

Which of course brings us to the poem of the occasion: “Some Sort of Chronicler I Am,” another Whitmanian exercise of the “transparent eye,” here focused on an AIDS victim ranting on the subway, a subject the poet expects we would rather he change. And so he does, drifting into light images of children playing in Battery Park, followed by observations about Williams and Stevens, and how they evolved notions of language during economic depressions. Williams, the physician, feeling the pain of his patients, decides counterintuitively to compress the speech he hears around him. Stevens, for his part, the lawyer dealing in “high-risk losses,” “suspend[s] his grief” and transposes it all into “thoughts, figures, colors” (162). Both poets further the aesthetic agenda set by Joseph in the opening lines quoted at the outset. The poet learns from them, in effect, how to abstract, what he managed to artfully postpone in the early work. The third exemplary poet in this poem, Yvan Goll, provides Joseph’s immediate subject — what Goll calls “Lackawanna Manahatta,” “half made of telephones, half made of tears.” And it is in this city “of pregnant nights” that the poet overhears the man in the bespoke suit pronounce to his much younger date: “from now on it’s every man for himself” (162–63). Everywhere in these splendid poems, greed and chaos threaten the Republic, and the poet retreats not into himself, but into language and images of hard-earned pleasure and happiness, and a hope for truth and transcendence:

[…] Of course I remember

that day — boundless happiness and joy.

The leaves in the park deep, irascible mauve.

The crippled unemployed drawing chalk figures

on the Avenue. Precisely. Where we ought to be. (173–74)

The last poem in the volume, “Occident-Orient Express,” with its worldwide vision, reminds one of those globe-touring poems of Frederick Seidel, a poet about whom Joseph has written admiringly.[4] Moscow, Bonn, Jerusalem, Lebanon, and Las Vegas are just some of the places in Joseph’s ken, but Tokyo stands out as the place where “Madame Lenine’s / grandniece eats air-blown tuna / pungent as caviar” (176). This provokes the poet to ask: “What do I mean?” And the answer is simple: “Language means.” And of course it is all about the “eye” — or, in the words of a taxi driver, “It’s in the eyes, / you have to break the other’s eyes.” In this brave, crazy new world of Joseph’s third volume, “pure abstractions blast through / a fragile mind” (177). The poet is poised for the next movement: the leap “into it.”

In Joseph’s most recent book of poems, the title proclaims the poet’s intent: he wants to immerse himself in the world; he wants to get Into It (the title of his 2005 collection). And he does so with a vengeance. This is a volume of staggering expansiveness. Despite the odd encrypted allusion to his past, or even an occasional “I,” this volume strips down its language and grammar, and expunges all gestures to personal authenticity. The poet here reaches full authority, a walker in the city who can also explain our apocalyptic anxieties in a most distinctly American voice. The voices come from everywhere: the street, the war room, the TV set, poets, and professors. Moreover, though still struggling with language and silence, the poet now knows what he really wants. In poem after poem, he seeks nothing less than truth and beauty, grounded in a profound moral sensibility.

An epigraph from Ovid suggests two important aspects of Into It: Joseph yearns for a voice — a voice, one imagines, different from the self-referential one of earlier work. Also, he needs “to tell the shifting story”:[5] these are poems about transformations and they are a shift from his previous work. The opening poem asks new questions: “[h]ow far to go?”; “And where?” (3). The answer begins passively: “a story took place” with “[c]haracters talking.” He quotes a woman, who is confused by competing “claims to morality” in a time of unparalleled violence (4). But the “I” — who could be anyone, really — now knows “the answer:” “beauty,” as seen, for example, in “the sun ablaze on the harbor.” Joseph, now a more philosophical and abstract poet, sees “[a]t center a moral issue” in “When One Is Feeling One’s Way.” Although he mentions Hillside Avenue, there is no sense of where that is or if it matters where it is. What matters are “two things:” “history and grammar,” “the chemistries of words” that allow for such phrases as “The fault lines / of risk concealed in a monetary landscape” (6). At this point Joseph gets into it in the historical, indeed classical, sense. “[S]ince the time of the Gracchi,” there has been the “same resistance,” resistance against “the arrogation by private interests / of the common wealth, / against the precious and the turgid language / of pseudoerudition.” Another poem suggests the role of language as we delve further “into it,” that some things “can only be said in that language, / opaque, though clear, painted language” (9). But it is also important to remember, with Wittgenstein, that “[t]he limits of my language / are the limits of my world,” as Joseph quotes him in “Why Not Say What Happens?” Even what happened in lower Manhattan on September 11, captured so eloquently in the poem “Unyieldingly Present” — a sequence of images — is “[a]n issue of language now, / isn’t it?” (36).

The cacophony of voices and the most “expert” of lies force an important change in the poet. Once the avenging angel of his Detroit, the poet becomes the recording angel of an era. He notes early on his “transcriptions of the inexpressible” during a time when “[t]he technology to abolish truth” is readily available (10). “Inclined to Speak,” a poem that worries about the role of poetry, looks towards Bertolt Brecht and Paul Celan, and knows that one thing “must be made explicit:” the truth (12). As if answering his earlier inability to abstract, Joseph titles one poem “August Abstract,” and it is, indeed, an abstract poem, despite its location on Twenty-Seventh Street, “not too far from Eleventh Avenue” (22). The poem asks, “the truth? The truth // that came to grieve, was aggrieved, for whom? / Truth determined alchemies of light.” Who are the enemies of truth? Obviously the dictators and warlords of history, and it is only that kind of “concentration of power on earth” that can strip truth “of its power” (24, 25).

The voices heard throughout the book are many. In “News Back Even Further Than That,” we hear from an air war commander, a president, a prophet, a woman made angry by war, and Ezra Pound — a typical Joseph mix. And that transparent eye begins to zoom in too close to the horrific reality:

[…] I’ve become

too clear-sighted — the mechanics of power

are too transparent. (41)

In his loose translation of Ovid, Joseph smartly makes the classical contemporary and vice versa. What is the difference between ancient and modern warlords after all? Both understand that “[p]ower knows of no argument other than power” (51). The poet responds: “Ugliness, when truly touched, the shock of beauty / is what turns the game around.” Therein lies the poet’s wisdom — a wisdom shared with no less than John Keats in the famous closing lines of “Ode on a Grecian Urn” (1819): “‘Beauty is truth, truth beauty,’ — that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” In any case, the poet speaking at the end of the poem could be any poet, from Ovid to Keats to Celan to Joseph, any poet in other words who feels, as Joseph writes in Into It, “bound by transcendent necessity” (52).

In an earlier poem in Into It, Joseph hears an obscure Sam Cooke tune on the jukebox, and the lyrics are a perfect echo of the Whitmanian voice of Joseph’s poetry: “even my voice belongs to you, / I use my voice to sing, to sing, to sing to you” (31). The final long poem of the book (“The Game Changed”) completes the circle. The poet is in Manhattan, attuned again to an interesting mix of voices: a lawyer, Osip Mandelstam, the Maronite Patriarch, a professor of international relations, a cab driver, a member of the Commission on Missing Persons, and a proverbial beggar. The lawyer, by the way, fully embodies Joseph’s sense of “chemically pure evil;” his very “presence” is “a gross and slippery / lie” (63). He mocks the poet’s opening observation that “the phantasmic imperium is set in a chronic state / of hypnotic fixity.” But the lawyer’s scorn does not matter, for the poet’s “melancholy is ancient” (64). And his intent is clear: “to make a large, serious / portrait of my time.” The poet knows that “the game” has changed. “Neither impenetrable opacity / nor absolute transparency” will explain it all (65). His mind is on fire, “possessed by what is desired.” And what is that? “Immanence — / an immanence and a happiness.” Far from the hyper-reality of the early poems, Into It ends in an abstract dream and sings a final hymn to the silence (“Once Again”).

In his recent book on contemporary poetry, The Modern Element, Adam Kirsch distinguishes the best poets of our time as risk-takers who exhibit a particular kind of heroism; such a poet aspires to be “civilization’s pioneer, undergoing earlier and more intensely the spiritual experiences his contemporaries have not yet learned to articulate.”[6] Furthermore, the poet achieves this with “daring honesty, subtle self-knowledge, an intimate […] concern with history, and a determination to make language serve as the most accurate possible instrument of communication.” Joseph evolves over the course of his four books into just such a poet. While the majority of contemporary poets, in Kirsch’s view, remain mired in their quest for authenticity, or retreat into impenetrable word play, Joseph manages to carve out a unique place for his work. Like Whitman and Seidel, he embraces the world around him in all its complexities and with a profound sense of history. He values the truth above all and no longer has to shout out his self-knowledge. His concern with language, his own and the voices he hears, are what make him, among other things, a truly American poet, and one whose work will surely last.

1. Lawrence Joseph, “Some Sort of Chronicler I Am,” in Codes, Precepts, Biases, and Taboos: Poems, 1973–1993 (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005), 160. Hereafter cited in text.

2. Joseph’s poem “I Was Appointed the Poet of Heaven” also appears as an untitled prologue poem in Shouting at No One (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1983).

3. See, for example, “He Is Khatchig Gaboudabian,” in Codes, Precepts, Biases, and Taboos, 36.

4. See Joseph, “War of the Worlds,” review of Poems 1959–1979 and These Days, by Frederick Seidel, The Nation, Sept. 24, 1990, 314.

5. Joseph, Into It (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2005), 3. Hereafter cited in text.

6. Adam Kirsch, The Modern Element: Essays on Contemporary Poetry (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2008), 11.

An introduction to Lawrence Joseph

Edited by Eric Selinger