On Etel Adnan's 'The Arab Apocalypse'

“Doesn’t the act of looking at an object become also one of its definitions?”[1]

I

L’Apocalypse arabe is a book-length poem composed in French by the Arab American poet Etel Adnan. It was published in 1980; Adnan’s English translation first appeared in 1989. Of the several rubrics under which The Arab Apocalypse may be read — hybrid text, visual poetry, surrealism, translation, postcolonialism — it is its nature as a work of witness that most commands my attention. Not least because it was written in response to and in the immediate context of the Lebanese Civil War (which broke out in 1975), but also because these other strands (the visual, the surreal, etc.) make the act of witnessing a provocative challenge to any notion of stability that may — innocently or otherwise — attend questions of representation in literatures of witness. In so doing, the text becomes a disaster in the process of witnessing disaster.

[2]

[2]

Carolyn Forché defines poems of witness as those that “bear the trace of extremity within them, and they are, as such, evidence of what occurred.”[3] Certainly, as the lines above indicate, The Arab Apocalypse offers evidence of violence, but to use the word “evidence” might suggest something like an objective — or at least unaffected — observer recording that which happens outside of her, offering to us the legible document of a holocaust. While I would not claim that Forché’s definition leans toward this paradigm, I would emphasize the ways in which “the trace of extremity” is borne by the poem of witness: how do its speakers, languages, and forms enact or become infected by the horrors to which they testify? I wish to read Adnan’s poem as one that doesn’t simply represent but becomes — and in becoming, weeps, interrogates, admits complicity, embraces; bears out, on the page, traces of extremity. Of the poem’s composition, Adnan says it began (one might say simply) as “an abstract poem on the sun” —

(7)

(7)

— but then the war broke out and “took it over.” She says, “I was so inhabited by that ominous sense of disaster, of madness, that only that way could I express it. … I was writing on explosion per se, on apocalypse per se and I saw it in color.”[4] The abstract poem becomes overcome.

II

There are at least three major ways in which the overwhelming and overwhelmed quality of The Arab Apocalypse radicalizes the genre of witness. Firstly, perception itself is a radical means of being in the world. Secondly, it is not clear how many witnesses there are, how stable they are, or even how human they are. And thirdly, language seems to ingest the violence it meets and, rather than record it, expels it out in sonically and visually fraught lines of meaning and nonmeaning.

That merely looking at the world might constitute a radical strategy should become more clear if one considers that Adnan is also a visual artist — and an immensely prolific one, perhaps most well known for painting California’s Mount Tamalpais over and over again, but never in quite the same way. In her artist’s statement Journey to Mount Tamalpais, Adnan quotes Ann O’Hanlon, of the Perception painters among whom she came of age: “To perceive is to be both objective and subjective. It is to be in the process of becoming one with whatever it is, while also becoming separated from it.”[5] In the intersubjective encounter between mountain and human self, both are constantly changing, even into one another. This philosophy and praxis is at work throughout Adnan’s oeuvre, and certainly also in The Arab Apocalypse, though the number and nature of the events “looked at” is extreme: they include the events of the first year of the civil war (1975–76), particularly the massacre of Palestinian refugees at Tall al-Za’tar and Quarantina, as well as other conflicts in the Middle East and around the world; the plight of Native Americans in the United States is evoked often. The speaker of the poem, presumably human, though never clearly identified as a single being,[6] seems to merge or identify with the violence, as though by a strange force of attraction, and at one point even declares:

![]() (26)

(26)

It wouldn’t be fair to explain away the surrealist logic at work here, but there is the sense that the speaker has become an amalgam of two major figures in the scene of the poem: the victimized Native American and the decaying sun. Simultaneously, the speaker is also the force that “plunges” (usefully? destructively?) Beirut in light (the beneficent light of the sun? the terrifying light of manmade weapons?).

Meanwhile, another narrative appears variously in the background or foreground of the poem: the disaster — slow and certain — of the sun:

![]() (42)

(42)

In other words, even as the sun illumines terrestrial, human-sourced catastrophes, it itself undergoes catastrophic change. Violence and decay are not merely being witnessed; they infect the very process by which we observe and record.

III

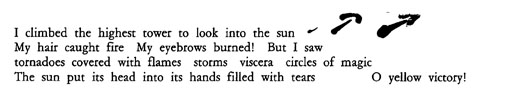

Even stranger is the fact that this dying sun appears to be actively involved in human affairs — or at least those of the speaker. As when the “I” climbs “the column … the mountain … the cloud … the sun” and as a result sees “masked men execute a carnage” (33), the sun seems to actually be facilitating the work of witness, granting the speaker a privileged vantage point —

(62)

(62)

— or even, through a strange kind of intimacy, becoming a collaborator in the poem:

![]() (17)

(17)

And while this collaboration seems at times productive and even friendly, at other times the relationship is adversarial, as though the sun and speaker were mythic rivals: “I took the sun by the tail and threw it in the river. Explosion. BOOM” (20); “I smothered the sun with an iron bar disfigured its words tore its face / And mine. Big black holes” (49). A major innovation of this text, then, is that there are at least two witnesses, one human and the other nonhuman, and that they are intersubjectively involved in the unfolding catastrophes. Thom Donovan suggests as much when he writes that Adnan, like Aimé Césaire, makes “the earth [her] collaborator, [her] texts/persons solar anuses (little suns shooting out of every orifice)”;[7] I want to take the argument further and say that the sun, as collaborator, is the other witness of the apocalypse, one who is at times sorrowful, “put[ting] its head into its hands filled with tears,” and at others wreaking havoc on the people of Beirut and of the world.

Or rather, to pull back a little, the sun plays so many roles[8] in the text that it is impossible to fully encapsulate its energetic, un-Apollonian, leaky character. Even to suggest that the speaker and the sun are two neatly delineated dramatis personæ is a fiction external to the text, for there is a powerful moment in which the one becomes the other in a kind of antisublime of material transformations:

(25)

(25)

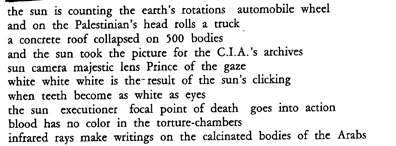

Even so, it is important to me to think of the sun as a witness to human politics. This is partly because I read Adnan’s sun not as some casual pathetic fallacy but as the endpoint of an extreme logic in which who else but the sun is left to witness us, and partly because the sun gives us a model, somewhat detached from our human selves, whose agency as a witness, whose dual ability to testify and to be cruel in testifying, we can critique:

![]() (7)

(7)

This dread is found in the very first poem. And then later, the sun’s gaze is explicitly cruel; it shaves away complexity:

![]() (59)

(59)

The camera metaphor is carried through to show the sun’s complicity in the violence, its transformation into an “executioner” —

(59)

(59)

— while the CIA seems to me a synecdoche for the world outside the Arab apocalypse (which has not ended), a way of implicating us all. And (or, however) the sun, as perpetrator,[9] is also a brutalized victim. It becomes the tragedy it sees:

![]() (32)

(32)

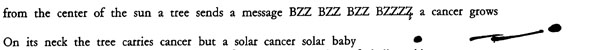

That is to say, as much as I call the sun a witness, it is not possible to keep this meaning stable. Elsewhere the sun is “a Syrian king riding a horse from Homs to Palmyra,” “LUCIFER,” “a shark pursuing stars in the sky’s seas,” “a traitor,” “a verb,” and “Nothingness” (9, 29, 33, 40, 43, 73); the sun’s meanings are mutant and cancerous:

(17)

(17)

A site of semiotic excess, the sun keeps ingesting — “cannibal anthropophagus” (19) — and expelling its meanings. And it too can be ingested and expelled: “eat and vomit the sun” (19), the poem commands us.

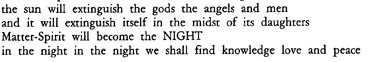

And finally, there is the prospective death of the sun, a critical future because

(78)

(78)

Night is an important time for Etel Adnan (it is also the title of her most recent book). Because light is Dionysian, violent, excessive, and imbalanced, it cannot sustain us; it is night that better nurtures our thinking. The emphasis on a perpetual night marks yet another radical aspect of the book because, in a way, witnessing is routed through a far-distant time, when the sun is visibly dying or has died already. Adnan’s record, if we can call it that, of the Arab apocalypse is not that of a survivor who remembers or a journalist who is apart from the violence, but one who is actively there, seeing, suffering, and even perpetrating; it is thus also a record of something acknowledged to be endless by the calendar of human history, of which we can only make sense when we arrive at some sort of cosmic finality of time. It is, as Thom Donovan writes, “An impossible remembrance. The remembrance of the body which experiences the pain of the cosmos. … What Jalal Toufic calls ‘undeath’; undeath as a condition of possibility for remembrance, and for bearing witness to human and non-human (cosmic, terrestrial) cruelty.”[10]

IV

As there is the radical nature of perception and ways of figuring witness, there is also language, which must enact them. But:

![]() (43)

(43)

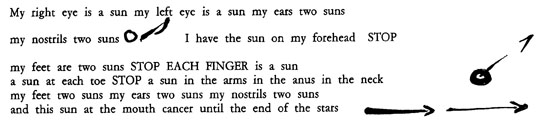

The decidedly visual nature of the poem insists on its own kind of radical looking, inviting the reader to witness something like the apocalypse of language. Language as material bears within it “trace[s] of extremity,” which is why it has been important here to provide images of the text rather than to transcribe the spacing and glyphs in some other way.

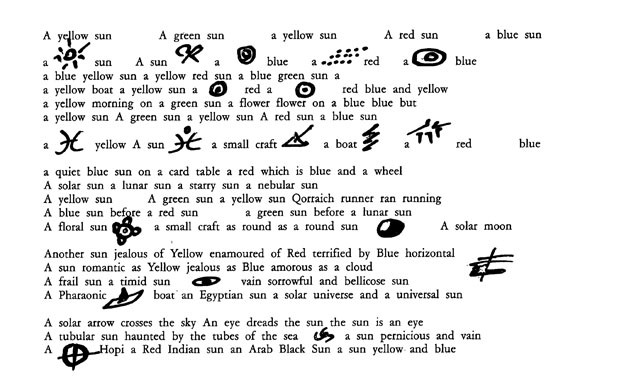

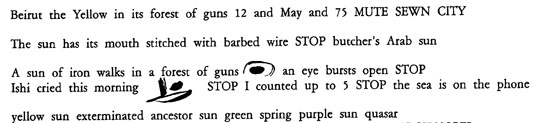

The Arab Apocalypse appears between orange covers, on landscape-formatted paper. A fair bit of white space surrounds each of the fifty-nine sections (for the fifty-nine days of the siege of Tall al-Za’tar, perhaps). The poem is in a hybrid language of English (or French) and the poet’s hand-drawn glyphs, many of which look like arrows directing the eye this way or that, telling the hand to turn the page. Other glyphs look like mutilated or setting suns, flowers, spirals, or exaggerated punctuation marks. The linguistic text is sometimes verbless, syntactically simple. Caesurae and the telegraphic word “STOP” take over from conventional punctuation. Long strings of the vocable “HOU” howl through the text, an eerie wind. The capitalization of these and other words grants them a power, a darkly festive air. The page is a theatre in which language acts out scenes from the apocalypse.

Of the glyphs, Adnan says, “the signs are my excess of emotions. I cannot say more. I wrote by hand, and, here and there, I put a word, and I made instinctively a little drawing, a sign. … Maybe it is because I see these apocalypses … because my first thought is always explosive. It is not cumulative.”[11] Like the speaker and the sun, the glyphs are not stable. For example, even in the same section, they do not look exactly alike in the three editions of the poem I have:

(39)

(39)

[12]

[12]

[13]

[13]

Whatever the glyphs looked like in the original French edition, to keep them looking exactly the same in the English translation would have been to disregard the dynamics of the glyphs, which came, as Adnan says, instinctually, as though approximating the force of external events and internal responses to them. So, I assume, the glyphs cannot be “fixed” in the way of linguistic paradigms, and they must be translated from French (the second glyph above is from a French edition) into English, but also from one edition to another, where, for example, the page size is different (the third glyph is from the Etel Adnan Reader, which has different page dimensions). Each performance of the play is new.

That “the language-circuit has burned” can be taken to mean both that language fails and that its usual mechanisms (circuitry) are insufficient. It must perform its dual capacity and incapacity to signify. Just as the glyphs are sometimes impossible to interpret, other features of the poem may be too easily interpreted, or interpreted in more than one way. For example, the telegrammatic “STOP” in poem VIII (i) acts as punctuation: it invites us to pause and consider two images, the first surrealistically precise (“an anemic sun loses a tooth a day”) and the second impossibly vast (“the war”); and (ii) issues an injunction: “STOP the war.”

![]() (21)

(21)

Or else, a string of the same word or vocable may generate an excess of meaning or sound, the text seeming to cry out of the page. In poem XXXV, two long strings of “STOP” and “HOU,” separated by a stanza, act as magnetic poles, perversely translating meaning into sound, or generating an agonistic field in which they oppose one another:

![STOP [x10] / a sun airborn a sun airplane circles up there ... / there is no water no plasma no air there is the radio / there are star fish streaking in the night / the Tuaregs arrive motorized empty-handed / HOU [x10]](/sites/jacket2.org/files/article-images/page54.jpg) (54)

(54)

As such, language too is a disaster and a witness, bearing “extremity” within it, being outraged.

V

CODA: SUGGESTIONS FOR READING THE POEM

(i) Read aloud:

I made gestures, arms flagellating, and hands jabbed the air finding release in spastic display. I supplicated. I improvised finger-mudras and worked taut, awe-inspiring expressions upon my face. […] Thus I put my whole body into the codes and lingual soundings of this animated and visual text, her Codices. […] I took the text’s ideograms as clues for performance and chanted “HOU HOU HOU HOU HOU” and “DOUM! DOUM! DOUM!” […] I spooked myself.[14]

(ii) Read the sun.

(iii) Read with the eyes of the living and of the dead.

![]() (72)

(72)

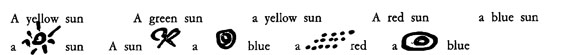

(iv) Read the glyphs.

It is impossible, but read the glyphs. Or: it is possible and read the glyphs. Readers seem divided on the issue. Caroline Seymour-Jorn says they are “enigmatic symbols that make reference to some hidden meaning.”[15] Sonja Mejcher-Atassi says they “do not represent anything other to the written text — visual as opposed to verbal — but rather emphasize the visual aspect of writing.”[16] Jalal Toufic says they are partial translations of the linguistic text that may jolt the Arab illiterate “into, at last but not least, learning to read — and then actually read.”[17]

I think the glyphs are partially intelligible. The arrow here verbs the meeting of the sun and sea in conjugal ecstasy:

![]() (9)

(9)

And here arrows mark cosmic flight paths:

![]() (28)

(28)

And here a pink dove shatters a human face:

(25)

(25)

But this intelligibility is inconsistent, idiosyncratic. The more abstract glyphs seem simply to denote bursts of energy or suggestions for the eye to move. They are loud; they communicate the urgency, the necessity of this text. But:

Once I visited a class taught by Eleni Sikelianos. We read about half of The Arab Apocalypse aloud, a poem a person, round the room. No one moved the way Anne Waldman did, but we did read aloud and we paused. I noticed how different people read the glyphs differently, but in silence. Some paused noticeably. I certainly did. And there was in that silence another power. I kept thinking of the glyphs as a lost language of the future, the language for when “in the night in the night we shall find knowledge love and peace” (78). But was even this too intelligible?

(v) Don’t read, but look.

At the text. At the world around it.

1. Etel Adnan, Of Cities and Women (Letters to Fawwaz) (Sausalito, CA: Post-Apollo, 1993), 22.

2. Adnan, The Arab Apocalypse (Sausalito, CA: Post-Apollo, 2006), 23.

3. Carolyn Forché, introduction to Against Forgetting: Twentieth-Century Poetry of Witness, ed. Forché (New York: Norton, 1993), 30.

4. Adnan, “Woman Between Cultures: Interview with Etel Adnan,” by Allen Douglas and Fedwa Malti-Douglas, January 8, 1987, qtd. in Lisa Suhair Majaj and Amal Amireh, introduction to Etel Adnan: Critical Essays on the Arab-American Writer and Artist, ed. Lisa Suhair Majaj and Amal Amireh (Jefferson: McFarland, 2002), 18.

5. Adnan, Journey to Mount Tamalpais (Sausalito: Post-Apollo, 1986), 11.

6. In fact, in poem XXII the speaker claims to be all of the following: “the prophet of a useless nation,” “a sniper with glued hair on my temples,” “the terrorist hidden in the hold of a cargo from Argentina,” and “the judge sitting in every computer shouting FREEDOM IS FOR WHEN?” (41).

7. Thom Donovan, “Teaching Etel Adnan’s The Arab Apocalypse,” in Homage to Etel Adnan: Lifetime Achievement Award, Small Press Traffic Literary Arts Center, San Francisco, ed. Lindsey Boldt, Steven Dickison, and Samantha Giles (Sausalito: Post-Apollo, 2012), 37.

8. “Adnan clearly uses the strength and intensity of the sun as a metaphor for colonial powers … [while the] sea, moon, earth and various specific groups of people, such as the Hopi and the Palestinians, variously represent the brutalized, colonial subject. … At other times, the sun seems to be a more general symbol for the violent potential of human beings. … However, Adnan’s sun also appears at several points … as wounded, or deteriorating, or even dead. … Finally, Adnan’s sun sometimes seems merely to be an element of a larger universe that follows its own cycles and is completely indifferent to the travails of human beings on earth.” Caroline Seymour-Jorn, “The Arab Apocalypse as a Critique of Colonialism and Imperialism,” in Majaj and Amireh, Etel Adnan: Critical Essays, 38–39.

9. See also: “O sun which tortures the Arab’s eye in the Enemy’s prison!” (10); “the besieged Palestinians walk on all four / the Great solar Circle has encircled them in its iron ring / And tired of words they begin to bark” (54).

10. Donovan, “Teaching Etel Adnan’s The Arab Apocalypse,” 36.

11. Adnan, interview by Hans Ulrich Obrist, in Etel Adnan in All Her Dimensions, ed. Obrist (Milan: Skira, 2014), 81.

12. Adnan, L’Apocalypse arabe (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2006), 33.

13. Adnan, The Arab Apocalypse, in To look at the sea is to become what one is: An Etel Adnan Reader, Vol. 1, ed. Thom Donovan and Brandon Shimoda (Brooklyn: Nightboat, 2014), 195.

14. Anne Waldman, “Sunken Suns,” in Homage to Etel Adnan, 92–93.

15. Seymour-Jorn, “The Arab Apocalypse as a Critique of Colonialism and Imperialism,” 43.

16. Sonja Mejcher-Atassi, “Breaking the Silence: Etel Adnan’s Sitt Marie-Rose and The Arab Apocalypse,” in Poetry’s Voice — Society’s Norms: Forms of Interaction between Middle Eastern Writers and their Societies, ed. Andreas Pflitsch and Barbara Winckler (Wiesbaden: Reichert, 2006), 208.

17. Jalal Toufic, “Resurrecting the Arab Apocalypse STOP [THE WORLD],” foreword to Adnan, The Arab Apocalypse (Sausalito, CA: Post-Apollo, 2006), 7.