Peter Minter: Feral habitus

Peter Minter is one of the greatest poets I read, and one of the greatest poets I know. I regard him, his conversation, his attention, his criticism, his aesthetics and his ethics as militantly tender, tenderly militant. Minter is uncompromising and committed in the things he makes and does, and his politics are manifest in his making and doing, interfacing variously with discourses and methodologies of an eco-anarchist left. As well, he is interested in relation and encounter, whether enacted through romantic love, creaturely relations, community action, activism, critique, skill-sharing, meal-sharing, etc. His particular relational affect is quiet, precise, concerned, intuitive, understated and dead-on.

In July 2011, Michael Brennan published an 'interview' with Minter for "Australia -- Poetry International Web," an online resource collecting extended interviews and works by poets. The interview is not so much an exchange as an extended response to a set of questions presented to Minter by Brennan. Rather than answering each question discretely, Minter's written response is a critical exegesis of his poetics that treats, in some way, each of Brennan's provocations. I mention this because it is by far the best primer for Minter's work and critical stance. Read it here.

Minter’s contribution to poetics (in Sydney, in Australia, in the Milky Way) is enormous. As the editor of journals and anthologies, as the curator of reading series and the publisher of occasional collections, as a scholar in Aboriginal and Australian literature at the Koori Centre in the University of Sydney, and as an active and attentive member of communities, Minter has contributed, for decades, to conversations around poetics, aesthetics, indigenous history, culture, praxis and politics. Minter was founding editor (with Adrian Wiggins) of Cordite Poetry and Poetics Review (now an online magazine edited by David Prater). He was the co-editor (with Michael Brennan) of Calyx: 30 Contemporary Australian Poets, published by Paper Bark Press in 2000. In 2008, he was the co-editor (with Anita Heiss) of the Macquarie PEN Anthology of Aboriginal Literature. He is a former poetry editor of Meanjin and the current poetry editor of Overland.

You can see traces of mid-twentieth-century America in Minter’s methodology for making – Olson, Duncan, Levertov, HD, Creeley, Williams, and other moments and coteries that dealt with the shifting, ecstatic, and catastrophic events of post-war internationalisms and its attendant macro-micro optic vacillations. There are also strains of the New-Romantic 1980s, as perceived by a teenage Minter in Newcastle, a steel mill city on the Australian east coast. There’s sci-fi in there too, with its tropic cues exacting specific fantasies and paranoias of post-cold-war bomb-oblivion. And it's queer, where queerness is a strategy for reading and positing a thoroughly multitudinous and anti-essentialist approach to imaging social and political relations. As a critic and commentator, Minter works against monoculturalism, neocolonialism, mediocrity, egomania, revisionist histories, rhetorics of ownership, entitlement, individualism and economic rationalism. Recently, he spoke out against the just-published anthology, Australian Poetry Since 1788, co-edited by Geoffrey Lehmann and Robert Gray. You can see a video of Minter’s paper on the anthology in Michael Farrell’s excellent commentary piece here on J2.

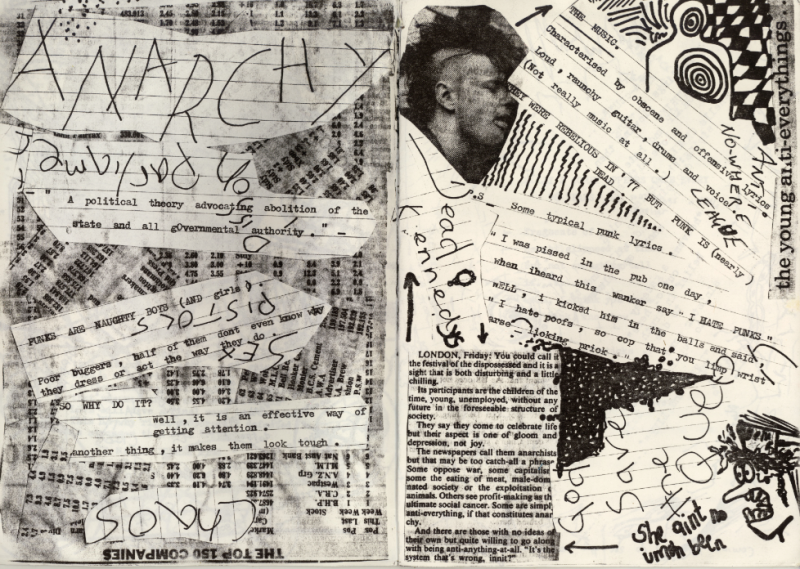

Minter is a fastidious archivist, and he has collected and organised all of his material from a very young age in boxes. He was kind enough to let me fossick through and harvest some nuggets for this post. The boxes included comprehensive records of his editorial, curatorial, and personal projects, including very early and yet-unpublished poems, which Minter has kindly OK’d for publication here. It also included a tiny book that Minter made in 1984 during high school that is heavily influenced by photocopied chaps he found in record shops in Sydney. He told me that he and his friends would occasionally get the train to Sydney to get haircuts, stock up on kung fu sandals and dig through the records and cassettes in the music shops on Pitt Street. There, they found pre-zine-culture magazines that were coming out of the UK punk scene, and they emulated the format in an edition called Altermatum Motivation. The cover image of an issue of Altermatum is featured at the beginning of this post.

The following files have been scanned and gifted by Minter. Many thanks to him for his time and generosity.

1. Altermatum Motivation, 1984, p.3-4

2. "On the Beach," a poem by Minter, written while in high school, and published in Young Hunter, a collection of poetry by young people in the Hunter Valley region of New South Wales.

3. Peter Minter, "the world up until now," written 1988-89, when Minter was an undergraduate at the University of Sydney. This poem is previously unpublished.

"the world up until now"

i

of all that could possibly happen,

this that happened was the right

thing, being necessarily ambiguous.

and they were saying “there is

nothing at all to fear, we are going

to be with you, all the way. just

relax, there will be nothing, nothing

at all to worry about.” the history

tree vanishes back into itself every

hour of the day, its leaves

growing smaller as they float slowly

to the shifting, hesitant ground.

from here, the world is

so much wider than it ever

seemed to all and such as we.

ii

how long has it been since

you arrived, fresh faced and

leaner than the sky? can you

remember anything or does it

hardly matter that behind those

holy marks you’re falling backward

motionlessly, through the schema

of life? can this be called

honesty, a body conducting

every word with its hollow

Shiva arms? this is an ever

growing dialogue, its paths can

take you anywhere, like an area

on the surface that develops silently,

a blindspot in a grassy place that

whispers sweet nothing to itself.

iii

there is a city, somewhere

behind the trees, in the wind.

we were there before, lying

in the ground, covered by roads,

sitting in the score of the world

without a single picture

or phrase that was magically

straight to the point.

iv

you can go fishing and see

in the fishes’ emerald gaze how it

really is under water. at such

times, at night, a wave of orange

in the grotto of the lookout, the

bird of fire on guitar and you say

that there are children, preparing

for the end. the cliff is civilized to the

point that it speaks ancient greek

and we, the last listeners, are as

clouds, forming ourselves from with

out. and the tree, overlooking

everything, is tangled in the wind

that sinks and pulls itself through

the taught and difficult matter of seasons.

v

sitting here, and the room

reassures itself that it is simply

a contracted immediacy, allowing

the flow of the traffic to sound in

through the window. there are no

more cigarettes, though someone

is sure to bring some, sooner

or later. an overabundance

of things can make you forget

how long it has been since you

came here and sat, waiting to see

the objects rise up with some

kind of recognition of themselves.

hopefully it will be easy, cutting adrift

them from “them”, though in the back

of our minds we know that nothing

is as easy as at first it seems. all

we desire is: a hint of the facts,

and to be floating in an all-white

clarity, subject of nothing, not even

words and their stale orchestralness.

vi

we can almost hear you, circling

in the currents, the incessant days.

its a marvellous way to die — imagine!

the randomness of the notes that play

the music in your head growing closer, closer

‘till they ripple in and outward over everything.

vii

from such a perspective the world

moves beyond itself, not a single

thought, just being at a locus,

a circularity of vowels that pass

song like through the world’s inarticulate

theme, its moments of careful indecision.

the vessel, colour of oak, the one

that never sees nor hears the

coming questions, is finally dissolved.

viii

it was always morning

as we left the fields. the

sky in the room was blue

on that winter’s day. from

outside these yellow walls

you hear a dog, barking. perhaps

he is chained to a tree, in a

pool of glinting dust.

ix

sleep and dreams become a way

of feeling the real weight of the future

as it grows like thick burgandy sap.

there is never any tense to such

occurrences, just the ebb of silent

summer and cool running water flashing

over rocks and lapping at the tediously

intricate traces left by creeping shells.

and it is difficult to decipher the images,

though they come, hands tied behind

our backs. it has something to do

with the reproduction of opposites,

a voice that pushes you down into

the waiting earth, that lets you

know where every meaning must lie.

x

it is sunday evening and we shuffle

around with pockets full of change, making

things to eat, listening to things

that happen on the radio. they

talk of bringing life back in order,

giving it a more definite kind

of nature. so that is the way of it

then, the sudden reversal of the terms,

the fascination of the effect.

xi

quivering in hollow ditches, goldfish

caught in seaweed nets from the settling,

humming air. we are standing by, we are

wondering – why, as the season lost itself

amongst the mild, flowering trees, did the

cat leave the tails and scales?

xii

from the mouth of the scarecrow

fall bulging pockets of words. he

must be nearly empty inside – the

birds fly, circling above, waiting

for his fall into the mere colour

of his clothes. the grasses shimmer

and grow between everything. an old

tree shudders in an air that

breathes slowly in from

the gradually sinking hills.

xiii

they come with documents to sign

that leave you without a single

responsibility. your house is getting

so wide it may soon be of natural

proportions. all that will be left –

a chair, a small table, maybe

some magazines, you could even

have them leave your papers and

a pen – all will appear both in

and out of focus, both cause and effect.

so, this is it, after years

of uncontrived engagement, where

days were full and fully collected

themselves and nights wrote diaries

on the finely tuned curves

of the satellites, as they slipped and

fell, without loss of energy, across

its thick, expansive black pages.

xiv

over and over, at this time of the

year, the days begin to outnumber

the nights, again. some people

will be thinking of the big

cleaning out – so this is it!

they cry as they kick the screen

door open with their left foot and

throw a box full of clothes and coloured ashes

out into somewhere out there.

xv

it is, so same have come

to mention on stormy afternoons,

a strange occasion, this life. as

strange as pulling apart a boat,

piece by piece, while out on the centre

of a lake. disturbances like this

come as cool reminders, first sipped

with hesitation, then poured into the body

with an enthusiasm that is sure

the more is taken away, the lighter

the space will appear. the fluidity

is almost blinding, and the grasses

they are possessed with waves of clouds,

with waves and signs of recognition.

4. Peter Minter, "Mosquito Sleep. Island of Formosa." written 1988-89, when Minter was an undergraduate at the University of Sydney. This poem is previously unpublished.

"Mosquito Sleep. Island of Formosa."

sleeping round in the countryside often leaves

our heads quivering with mosquitoes. afternoons are

then like dreams: they never find their middle

caught between the beginning and the end;

there’s just the glowing immanence. this is

where the head likes to rest itself, unwind,

uncurl itself as would a snake; there, it is watching.

could be lying out there on that rock, waiting

for that wave to finally wash our skins from ourselves.

these hardened branches, autumn clinging to

the clothes with twigs and disturbances, a

dieing spectre that rests into the ocean waves.

from here it is still a little hard to see, though

sometimes the planes that cruise in over the water

hang like slowly falling moons and glow across

the wandering black space.

an old story tells us that years and years ago whales

once came to this rock and in the morning

they beached themselves and made thunder

in the sand that now shifts

under the weight of the experience.

in a context such as this we are made

totally unmanageable — it reminds us of our childhood.

it reminds us of someone we once

know who disappeared across the edge

into the waves. and the rocks are

of such odd shapes. they have no real positions.

they have no real names.

if this island were to crumble away we would

need to find a way of winning over nothing.

on the ends of ourselves we are dancing

this confusion — we have seen all the steps to be

taken in life and this poisonous knowledge aims

itself at our stomachs, and we are dancing

this confusion with our lives in our hands.

if we could see into the centre we may see

a hole of white coming from about; it is

hovering here just below us. if we happen

to dive inside it we swim like fish

round and round in a hollow green savanna

where everything needs painting, where

everything needs to rest.

these forms, accumulating gradually, leave shapes

and instances of themselves. it doesn’t matter

how they look or what they mean. you can

see it in their eyes; they know a language made

of pictures that have their origins on bones,

a matrix of suspicion making sculptures in words,

the movement of fingers, the pixillating blink.

in the middle of the night black ibisis

seek the words that lie hidden

deep within our ears. they have come

from nowhere and the reasons for their

interest in such things are uncertain. the

ibisis always fly home high above the

beaches, wide angled as clouds.

when we speak together we like to make up

stories, we like to plan our escape — there is little

time left to go before this rock disappears

and takes all the heaviness of the surrounding land

with it. other times we lie together, dreaming

that the sky will shortly speak

to sculpt is lean.

5. Drafts and final versions of the "Varuna New Poetry Broadsheet." Minter published these broadsheets to correspond with the reading series he curated at the Varuna Writers Centre in Katoomba (1994-1998).

6. Drafts from Empty Texas, Minter's first full-length poetry book, published by Paper Bark Press in 1999 (a smaller folio containing some of the poems had been published under the same title by Salt the previous year.) These drafts represent only a fraction of the paper-edits made by Minter for each poem in the collection. These drafts were composed and revised during 1997.

Fossicks and offerings from Sydney