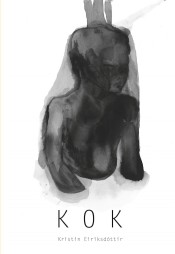

Kok og okkur

Kristín Eiríksdóttir beyond the book

Kristín Eiríksdóttir and I sit with her new book of poetry, Kok (Icelandic for Throat). The book is penned in Icelandic, and Kristín has performed a preliminary Icelandic-to-English translation of the text to accompany the book’s launch. Kok partners Kristín’s visual art with her meditation on relationship. The long poem touts simple diction in repetition, occasionally confronting syntax shift, and an unexpected end-before-the-poem-ends that wrenches the reader’s heart through her gut via quick sucker punch. Kok is poignant, bare, driven. It captures exactly that moment when a body becomes struck with what’s stuck.

We sit with her English translation on screen and an Icelandic print-out in hand. The computer and print-out cycle between our hands, fluid reference points as we compare her translation with the original. Several times we confront Icelandic words too difficult to translate. Ykkur. Tæringu. Í snertingum ykkar ganga snertingar okkar aftur. “I get scared when language fails like this,” Kristín says of a moment where an Icelandic phrase is untranslatable to English.

We stare at a list of verbs and their homophones:

og doða og dofinn

og deyfa og drafa

og dvala og dulu

og dofa og daufur

og far eftir

sylgju

A literal, semantic translation destroys the alliterative emphasis on ‘d’ and the two-syllable construction. It’s not possible in English to move through different states of numbness, as denoted in this collection of Icelandic verbs. I propose to place the semantic translation as a secondary concern, instead satisfying the transfer of alliteration and consistent syllable count. We study words-in-translation embedded elsewhere in the text, lift them, then sound:

and not and known

and numb and knelt

and nude and none

and knot and neck

and a mark from

a buckle

An atmosphere, stark and terse, slides fluently between the languages despite the compromised meaning.

Two weeks later, Týsgallerí hosts Kristín’s book launch and an exhibition of the visual art in Kok. Downtown Reykjavík, Týsgallerí’s neon-orange front door opens into a petit two-room gallery. The recently opened space has swiftly become a favourite over the past year, featuring fascinating, new projects by contemporary local visual artists. The gallery recently hired Ragnhildur Jóhannsdóttir, co-editor of the women-focused visual art magazine Endemi and creator of an impressive visual-poetry series of treated cut-up book sculptures.

In the first room of the gallery, Kristín has hung a large, single watercolour. This work first exhibited two months earlier as part of a collaborative installation with Kari Ósk Grétudóttir and multi-person performance at Verksmiðjan á Hjalteyri in northern Iceland. At this earlier event, Kristín read excerpts from Kok before I read excerpts from Áfall / Trauma, Icelandic musician Gestur Guðnason powered long, ragged chords through his electric guitar, and Canadian visual artist Jim Holyoak broom-swept paint onto a factory wall. First exhibited in the factory’s vast echoic space, Týsgallerí provides intimate counterpoint to view Kristín and Kari’s cervical, raven-ink work.

In the first room of the gallery, Kristín has hung a large, single watercolour. This work first exhibited two months earlier as part of a collaborative installation with Kari Ósk Grétudóttir and multi-person performance at Verksmiðjan á Hjalteyri in northern Iceland. At this earlier event, Kristín read excerpts from Kok before I read excerpts from Áfall / Trauma, Icelandic musician Gestur Guðnason powered long, ragged chords through his electric guitar, and Canadian visual artist Jim Holyoak broom-swept paint onto a factory wall. First exhibited in the factory’s vast echoic space, Týsgallerí provides intimate counterpoint to view Kristín and Kari’s cervical, raven-ink work.

At the launch, Kristín reads in the small gallery room with the large ravening cervix, people packed in, sitting on floor and standing. My partial understanding of Icelandic twins with recollection of the English translation, and I’m caught between languages. Neither dysfluent nor confluent, but stuck. Lodged. Kristín reads aloud “OG SVO OG SVO” and I shimmy in the between of og, svo, and, so.

Later Kristín and I record her reading Kok’s entirety in Icelandic. As she listens in headphones to the recording, she speaks aloud her English translation, attempting to align the texts exactly. I record this bilingual experiment, Kristín’s voice resonant and dissonant. She notes afterwards that her voice in English is pitched higher, likely to differentiate from the primary pitch established in her Icelandic recitation. We listen to the flat affect of her Icelandic counterpoint her urgent, emotive English.

A few days after the launch, Kristín needs to frame four artworks from her book — three watercolours and a visual poem of knotted sentence fragments. We drop by Týsgallerí, enter the alarm code, and abscond with her prints. We head to Morkinskinna, a frosted-window store on Óðinsgata with mysterious allure.

Morkinskinna. Mouldy skin. It was on this that ancient Icelandic sagas were penned. As a 21st-century physical space, Morkinskinna-the-store is more a workshop fantasia where owner and apprentice build frames by hand. Morkinskinna: the page is the frame.

Kristín introduces herself and shakes hands with the owner upon entering. The frame studio is a craftworker’s haven; all surfaces, cabinets, and cubbyholes overflow with work. Drills, matte board, fine paper, containers with metal clamps, three tubs of broken glass, a lathe, slender wood, pencils. A large, antique iron handpress from Leipzig lurks by the door. Kristín and the owner speak in Icelandic as I inspect the surrounds. I spot ivory linen bookbinding thread with an oversized needle poking from its spool. A bone folder rests half-hidden beneath assorted trimmed paper on a drafting table. Framed artwork fills the walls, identified by Icelandic names and words — Úna, Kjarval, fegurð.

“What do you think, Angela?” Kristín points to a black wood frame surrounding a handwritten envelope, then a nude wood frame embracing bright pencil-crayon art. Three of her works have black watercolour in them. The black frame would surely emphasize that, but the nude frame seems more reminiscent of her paper. What frames the images in the book? Kristín tells me she prefers the lighter frame.

After this adventure we head to Crymogea, a fine-art and non-fiction publishing house located downtown on Baronstígur. My plan is to acquire a copy of the 2012 publication on typesetting history and peculiarities of the letter eth (ð). I have a long-held crush on books produced by this publisher because of their superior attention to quality in typesetting, book design, and materials.

We meet Crymogea’s publisher Kristján Jónasson and visual artist Hrafnkell Sigurðsson, poring over proofs of Hrafnkell’s forthcoming book presenting several of his photographic series from 1996 to present. As Kristján takes a phone call, Hrafnkell flips through the proofs and colour-corrected images with us. Hrafnkell is a former art professor of Kristín’s, and supported the publication of her first poetry book Kjötbærinn in 2004.

Midway through the proofs, Kristín looks at me goggly-eyed, excited, and breathes how thematically similar my work is to Hrafnkell’s. Trash, glaciers, volcanoes. Hrafnkell sources asemic writing and pattern in repainted ships, dirty snow clods from tire wells, and trash bales bundled at an Icelandic landfill. The book opens with underwater wire-grid forms submerged like icebergs; midway through the book, trash hovers as it’s transported, similarly framed. According to Hrafnkell, this unanticipated and unintended rhyme emerged across nearly two decades of creative output when assembling the book. His photographs catch ephemeral shapes in their transitional stages. Active gerunds. Melting. Renovating. Photographs lodge these temporary vocabularies in the eye’s cervix.

In the throat. Eye. Caught. Stuck. Offered for examination, without comment. In Iceland, such momentary arrests strike the body as a politics of generosity. We’ll speak and see beyond that between; we push through.

AÐ LANDA