I'll follow you

In my last post I discussed Vito Acconci’s concept of the “activist flaneur” and I mentioned how the figure of the flaneur is said to have originated with Edgar Allan Poe’s story “The Man of the Crowd.” Poe’s narrator, while engaged in categorizing the faces that pass his cafe window (using a particularly 19th century set of assumptions about character traits), is suddenly taken aback by a face that defies classification. He quickly grabs his coat and spends the night following the man through various crowd scenes, trying to determine what kind of man this could be. I won't give away the answer for those who haven’t read the story, but I’d like to make a connection between that act of following and several others — including Acconci’s 1969 “Following Piece.”

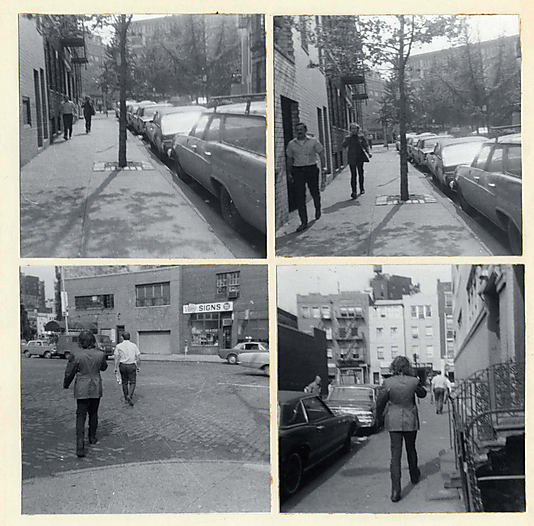

Acconci described the procedure of the work this way:  “Once a day wherever I happen to be, I pick out, at random, a person walking in the street. Each day I follow a different person; I keep following until that person disappears into a private place (home, office, etc.) where I can no longer follow…episodes of following ranged from 2 or 3 minutes — when someone got into a car and I couldn’t grab a taxi fast enough… — to 7 or 8 hours — when a person went to a restaurant, a movie…” Acconci enacted this procedure for a month, and he recorded the details of each “episode.”

“Once a day wherever I happen to be, I pick out, at random, a person walking in the street. Each day I follow a different person; I keep following until that person disappears into a private place (home, office, etc.) where I can no longer follow…episodes of following ranged from 2 or 3 minutes — when someone got into a car and I couldn’t grab a taxi fast enough… — to 7 or 8 hours — when a person went to a restaurant, a movie…” Acconci enacted this procedure for a month, and he recorded the details of each “episode.”

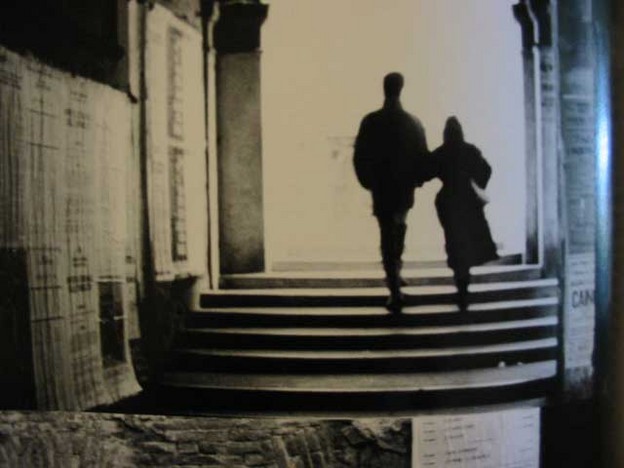

Ten years later the artist Sophie Calle performed her own extended following piece in Suite Venitienne. At a party in Paris, Calle meets “Henri B.,” who announces that he is leaving for Venice the next day. Calle also goes to Venice and after some detective work, figures out the hotel at which Henri B. is staying. She disguises herself and follows him through the city, photodocumenting along the way. The published account of this particular pursuit is part diary, part photo-novel, part investigative reportage.

In Paul Auster’s novel City of Glass, an author named Quinn is mistaken for the detective Paul Auster. On a whim, Quinn takes the case and finds himself following Stillman, tracking his movements with the same details as Acconci. But Stillman’s movements are quite erratic and seem to have no logic to them. Once Quinn tracks the coordinates of Stillman’s walks on a map, he discovers that Stillman is tracing letters with his movements and spelling out a phrase.*

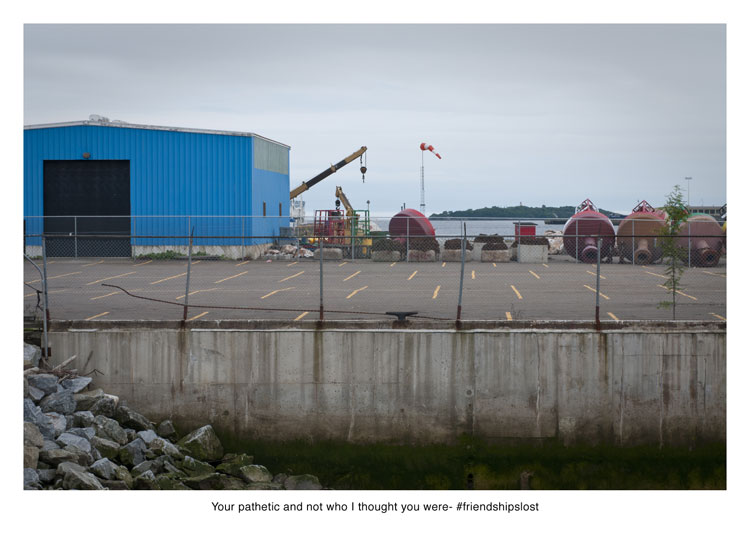

Each of these followings was performed with varying degrees of investment in the person being pursued. For Acconci and Auster, the subject of pursuit is random, and so we learn much more about the pursuer than the pursued in these cases. Auster’s detective, however, senses that a puzzle could be solved if he could understand the motivations of his mark. In this regard, he has more in common with Poe’s 19th century narrator, who eventually discovers that his “man of the crowd” has no existence outside of the crowd; the crowd is lifeblood. Such a plight resonates in the era of Facebook friends and Twitter followers. We are all followers now. Which leads me to one last following piece: Geolocation by photographers Nate Larson and Marni Shindelman. The project begins by collecting and tracking digital breadcrumbs. Here’s their description:

“Using publicly available embedded geotag information in Twitter updates, we track the locations of users through their GPS coordinates and make a photograph to mark the location in the real world. Each of these photographs is taken on the site of the update and paired with the originating text. We think of these photographs as historical monuments to small lived moments, selecting texts that reveal something about the personal nature of the users’ lives or the national climate of the United States. It also grounds the virtual reality of social networking data streams in their originating locations in the physical world while examining how the nature of one’s physical space may influence online presence.”

I’ve been trying to think of poetic projects that are analogous to this photographic digital following project. Although I’m not sure it’s a perfect match, the works produced by the Troll Thread Collective mine and recontextualize the language evidence of our virtual landscape in a way that allows us to follow (and see ourselves in) the crowd.

* If Quinn had been tailing Stillman today, a GPS tracker or an app like “Map My Run” could have made his transcribing a lot easier.

Psychogeographies