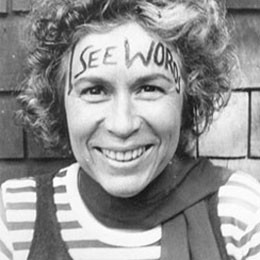

Hannah Weiner and intense autobiography

The following talk was presented at Rex Regina gallery, Bklyn NY this past fall at the invitation of Stacie Johnson.

Before I talk about the poet/live artist/clairvoyant journalist Hannah Weiner today, I would like to talk about a term that I have been using to describe a certain form of autobiography, namely “intense autobiography.” (I have used this term previously in essays about Bhnau Kapil and Jalal Toufic).

Basically, I want to use intense autobiography to describe self-life-writing practices (the literal translation of auto-bio-graphy) that stray from the genre of autobiography, in which one provides the facts of their life, from birth until present, usually late in life. While intense autobiography exists in relation to these forms of self- or person- writing, it is different. And where it differs largely are in two respects: 1. That writing is not a transparent, narrative means of making self or person appear retroactively, but the very means through which the person/self comes into being in relation to a social milieu; 2. Through intense autobiography the “body”— that container demarcating human personhood and rights — becomes a site of experience and experimentation where the limits of the self are related, if not often contested, in relation to a public, community, and/or social discourse.

Intense autobiography can also refer to a series of practices upon the body, much as Foucault spoke of disciplinary practices in terms of a “technology” or “care” of the self. The body-self is a site where subjecthood is negotiated and contracted; where disciplinary boundaries and biological essences are tested; where the body as a territory is both mapped and deterritorialized, as in the many well-known cases outlined by Deleuze and Guattari. What I want to talk about when I talk about intense autobiography is how self-life-writing demarcates social, biopolitical, and geocultural thresholds. Through forms, and not simply a received narrative writing which blandly insists on a continuous definition of self as a contained or enclosed interior, I believe writing and aesthetic forms may present the movement and passage of person/self/subject through a duration (where intensity refers to movements in time, and extension may relate movement in space). This writing is about becoming; it is about movement and undergoing; it is also about undertaking a radical empathy by which “self” and “other” and milieu and environment inform one another, as much of the most remarkable poetry and art of the 20th century has ventured. Form is necessary to the prospect of a radical autobiographical writing practice, because it is through the discovery and invention of forms that the subject becomes observable as a series a thresholds relating inter-subjective, psychosocial, and biopolitical exigency — the very urgencies that autobiography, as a genre, normally excludes.

But let’s move now from generalities into particulars, since what is at stake here when we speak of intense autobiography in relation to problems of form is nothing less than the specificity of certain bodies, and those bodies’ experiences in relation to a scene of cultural production, rather than others. The story has been told many times now, by many scholars and poets more qualified than myself. In the early 70s the American-born poet, visual artist, and fashion designer by profession, Hannah Weiner, started to experience auras in her environment. These visions are documented in two journals Weiner composed in the early 70s, The Fast and Country Girl.

Something remarkable about these journals is how entirely original the writing still seems to me today, if not the experiences they are describing, and yet how utterly appropriate we can understand it to be given that at this time Weiner was thoroughly embroiled in a community of artists, poets, composers, and other culture workers investigating intermedia, durational performance/live art, and radicalizing journalistic writing practices in every conceivable way. Two exemplary contemporaries of Weiner’s from this time period are her friend Bernadette Mayer, in whose Studying Hunger Journals she admits to having a similar synaesthetic experience to Weiner (seeing colors when she writes) and trying to make this experience visible through the use of colored pens.

Other exemplary contemporaries include Vito Acconci, who we all know was using his body as a site of investigation and information throughout the late 60s and 70s, and who also had recourse to journal keeping. In general, we might also say that New York School poetry from the 50s onwards was defined by a radical transfiguration of the self/author/body within a social scene, something dramatized at its inception by O’Hara, and which continues with Eileen Myles and other latter-day NYS poets today. Curiously the visual artist Lee Lozano, whose 68-72 journals recently became available in a facsimile via Primary Information, offer a series of durational pieces documented by writing, based on drug use (Marijuana, LSD, caffeine, alcohol, cocaine), the cultivation of specific dietary and sleeping regimes, and the enforcements of cultural constraints (avoiding women, in/famously). Lozano was also a friend of Weiner’s, Weiner showing up in a few of her pieces, and notably her “money” piece in which the artist asked friends to give and take from a common pot over the course of a week.

60s/70s art, we may argue, is in many ways defined by intense autobiography, inasmuch as it was the trend to experiment upon the body through lifestyle decisions, communal habitation, and sexual practices, and through an experimental regimen of drugs, diet, and exercise. Such were the times. What makes Weiner most radical among her peer group is her own response to this milieu through unprecedented forms of composition and performance.

After seeing auras for some time, Weiner started to see words on her self and within her environment, as textual hallucinations. In an essay Weiner wrote for Lyn Hejinian’s and Barrett Watten’s Poetics Journal in the 80s, "Mostly About the Sentence," she describes how these hallucinations result in a composition practice:

I bought a new typewriter in January 74 and said quite clearly, perhaps aloud, to the words ( I talked to them as if they were separate from me, as indeed the part of my mind they come from is not known to me) I have this new typewriter and can only type lowercase, capitals, or underlines (somehow I forgot, ignored or couldn't cope with in the speed I was seeing things, a fourth voice, underlined capitals) so you will have to settle yourselves into three different prints. Thereafter I typed the large printed words I saw in CAPITALS, the words that appeared on the typewriter or the paper I was typing on in underlines (italics) and wrote the part of the journal that was unseen, my own words, in regular upper and lower case." (quoted in Hannah Weiner's Open House, ed. Patrick F. Durgin, Kenning Editions, 2007)

Many scholars and other poets have speculated about the meaning of Weiner’s “clairstyle.” To what extent it depends on her abuse of LSD; to what extent it is a schizophrenic or psychotic expression; to what extent it is an effort to extend her early interest in communications theory and cybernetics. Of course it is a manifestation of all of these things, and more.

In terms of intense autobiography, what has always interested me about Weiner’s work is to what extent the writing seems consequential to her very being, as though in a literal way her life depended on writing. Bodily and psychic harm lurk in nearly everything Weiner undertook in the name of her art.

The Fast was originally called “The Hell Manuscript,” and I imagine this is because Weiner — who was in extreme physical pain from the various auras she was experiencing, and from biochemical reactions to objects in her environment — was literally “going through hell.” When I read The Fast I am reminded of Artaud, who of course Deleuze/Gutarri use as their principal case for what they call famously a “body without organs.” When, incidentally, I mentioned that term to my friend Robert Kocik, he said that of course Artaud would want a body without organs, his own organs being the source of profound spiritual and physical agony. What The Fast, Country Girl, and eventually Clairvoyant Journal record is nothing less than a radical transformation of every aspect of the self/person called “Hannah Weiner.” The self as a biochemical entity; the self as defined by a “soul” who can experience states of heaven, hell, purgatory, bardo, dharma, etc.; the self as conditioned by pleasure, pain, and access to medicine/health care.

After Weiner’s retreat in upstate New York, during which time she wrote Country Girl, she returns to the city to write the journals that lead up to Clairvoyant Journal. What is remarkable about Clairvoyant Journal is how it literally changes your neural pathways when you read it, as though writing could provide a contact high. There is a distracted way to read Clairvoyant Journal and subsequent books by Weiner written in the “clairstyle” form she would become known for, yet there is no way to undergo the syntax and not be altered by it.

As an experiment with my students last spring, I had them attempt to write a journal entry of their day in the style of Clairvoyant Journal. Almost none of them could come close to it, to my disappointment but not to my surprise. What I received instead were catalogues of events, thoughts, and perceptions that had occurred to them in the course of their days (it was an evening class). In Clairvoyant Journal there is none of this sequentiality. The syntax is a hyper-cubistic jumble of impressions, facts, utterances, declarations, feelings, hunches, observations, perceptions, addresses, and commentary about the fact that writing is occurring. As I tried to explain to my students, in this class about cybernetics and writing, Weiner is the original Facebook comment stream. She is social media before such a thing could come into existence. Reading Clairvoyant Journal is a little bit like being in a 2000s chatroom or comment stream, though not nearly as linear, where, as Myung Mi Kim once pointed out to me, phrasal units are smashed together and holographic, like a series of slides stacked on top of one another. Though at other times words are like actors doing things with words, gesturing in Steinian fashion; or they cut-off mid-thought/phoneme only to begin again somewhere else on the page. Not so much "stream of consciousness" (my students love to use this term to describe Weiner's writing), but forms of meta-writing which anticipate the Web 2.0 generation.

I often like to say that Weiner is our contemporary, because she anticipated forms of writing and reading practices unaccomplished during her time. Her textual hallucinations and elective telepathy are now our reality, whether we like it or not. And yet, interestingly, it is difficult for students to imitate Weiner, blocked perhaps by an illusion of immediacy. Which is to say, Weiner’s autobiographical intensities are only given proper expression through forms “up-to-the-task.” “If you had to grasp the immediate data of your consciousness, how would this appear in writing?” This was one of the prompts I gave to my students. It takes either a total giving in to a different form of preparedness to write (and remember while writing, juggling multiple thought-paths and perceptions at once), or a revisionary practice that is radically interruptive, to accomplish what Weiner accomplished through her work. As her manuscripts exhibit, her writing is a combination of an improvisational practice in which she could switch on and off multiple thought-channels, and a practice of revising the work that intensified its cybernetic simultaneities.

Through these simultaneities, as in the social media of today, we can feel the public and the private, socius and polis, community and domus, exteriority and interiority, friend, lover, and stranger colliding. It is all here, all happening, like angels on the head of a pin, undergirded by a reflexive consciousness — or feedback mechanism — that calls into question the imposed boundaries of any writing practice, the power structures of writing, and literary community, and authorship Weiner would interrogate throughout her career, until the very end.

Weiner’s legacy, hardly recognized by contemporary visual art or poetry worlds alike, is still very much with us today. I am reminded of it in New Narrative writing (itself neglected by contemporary scholars and critics), and especially in the use of various questionnaires by Dodie Bellamy and Robert Gluck to solicit private information from their friends and community for use in their work. I am reminded of it in Bhanu Kapil’s writing, whose syntax gives shape to migratory consciousness and geopolitical displacement. It is also present in various constraint-based somatic writings: CAConrad’s “(soma)tic poetry exercises”; David Buuck’s site-specific performances at Treasure Island and other sites of ecological abandon; David Wolach’s recourse to “distracted” methods of composition as a way of undergoing the condition of endangered others—the tortured, the stateless and oppressed; Amber DiPietra’s writing through the constraint of built environments and institutional structures unaccommodating to the disabled. It is present in too many lyrical and conceptual practices to name here. One could even see some of the Ryan Trecartin’s language in relation to Weiner, where he also seems to be attempting to find a shape for biopolitical exigencies within heterogeneous language practices, but especially language use as it traverses neoliberal-corporate personhood. In the number of writers like Suzanne Stein, Dana Ward, Brandon Brown, Jackqeline Frost, and others who would attempt to retain something “living” in the archival forms their writing assumes, I think that Weiner’s spirit persists.

A question too few writers have asked themselves, I believe, is what is lost — what fidelity to experience, and specifically to writing as a integral aspect of experience — when we do not consider writing as a form on the move, inadequately grasping at something real about the structure of embodied consciousness, or simply the relations that are formed through language with others — a world exterior to us, or simply beyond the individuation of consciousness. Weiner’s writing, like all writing and art that can be valued for its transgression of received forms, consistently shows us the extent to which writing can provide one with an affective and mindful experience wherein social reality is not merely represented, but simultaneously and inextricably produced, co-constitutive with its mediation.

And I think this is where writing, and poetic writing specifically, must continue to dwell in the future. At these ambiguous borders where the “self” becomes defined through environmental and social forces that would call into question the ground upon which such definitions and boundaries and borders of the self-life-written are founded. A writing that is not only visionary, in other words, but permanently shifting, permanently becoming other to itself, if only in its utter commonality. Sex, gossip, pain, consumption, production, biological function, housing, self-doubt and reflection, friendship, community tension, emotion, affect, perception, sensation: this is the content of the work, like all art and literature. It’s how we must experience this content, received through a qualitatively different set of formal necessities, which complicates what it means to perform self-life-writing at the thresholds of both a writing practice and one’s being alive.

SELF | LIFE | WRITING