George Woodcock and aesthetic tactics

The wonderful Vancouver poet Daphne Marlatt was recently the recipient of the 19th annual George Woodcock Lifetime Achievement Award (administered by the City of Vancouver and the Vancouver Public Library). It was also Woodcock’s centenary, and I was asked to say a few words about him.

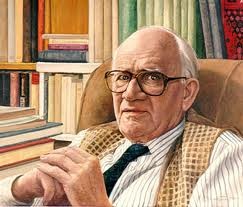

I imagine that there are fewer and fewer people who remember George Woodcock, who died some 17 years ago. He was a highly influential Canadian “man of letters” (as they used to say) — a poet, critic, travel writer, and author of biographies and other popular works of non-fiction. The founding editor of the journal Canadian Literature in 1959, Woodcock was also an influential political thinker, whose books on anarchist philosophy perhaps did more to popularize that ideology than any other publications in the decades immediately after the Second World War.

What interests me about Woodcock is the fact that these spheres of activity — the literary and the political — appear to have remained fairly distinct and discrete for him, throughout much of his career. Indeed, in the preface to Notes on Visitations, Poems 1936-1975, he writes:

“When I assembled my Selected Poems in 1967, I adopted a principle of choice which I now realize was too exclusively aesthetic, with the result that many poems inspired by political or moral passion were left out.”

There are no doubt many factors pressuring a poet to make such a decision — not the least of which would be the long shadow of Modernism and T.S. Eliot (Woodcock grew up in England and began writing poetry in the 1930s). However that may be, much of the best political poetry (and I do think Woodcock’s is good political poetry) is written by poets living through times of intense social turmoil (think of the poetry of Latin and South America through much of the twentieth century), and these poets rarely see hard and fast lines, let alone feel a need to choose between, the aesthetic and the political.

I think, for many poets today, we are more and more living in such times, where the urgency of the growing divide between rich and poor, global economic and environmental crisis and collapse, and increasingly oppressive governments intent on austerity programs, fuels the sense that to pursue “purely aesthetic” ends now is to fiddle while Rome burns.

Our aesthetics are never completely separate from our social contexts. The more interesting question to me these days is not whether or not a poem makes direct, explicit political/social reference, but the context in which poetry is written and read, the communities it presumes, instantiates, and participates in, and the solidarity it produces — both within that community, and between potentially allied communities. If I introduce a poem by saying that I employed such and such a procedure or constraint, or if I say that a poem was written in solidarity with such and such a political struggle, what is actually on the page will in some ways take a back seat to the invocation of a community present in these “external” contexts.

I neither believe in one political tactic for all times and places nor in one aesthetic practice or technique for all times and places. I think, so long as we are working through communities, and towards solidarity between communities, from the bottom up, then a certain degree of political and aesthetic profligacy is healthy.

In other words, if we can speak of a “diversity of activist tactics,” can we also imagine a “diversity of aesthetic tactics”? I am increasingly drawn towards such an idea.

Here are the closing stanzas of one of the poems Woodcock withheld on aesthetic grounds — “Sunday on Hampstead Heath”:

And in the broken slums see the benign lay down

Their empty useless loves, and the stunted creep

Ungainly and ugly, towards a world more great

Than the moneyed hopes of masters can ever shape.

In the dead, grey streets I hear the women complain

And their voices are the sparks to burn the myth of the state.And here where my friends talk, and the green leaves spurt

Quietly from waterlogged earth, and the dry leaves bud,

I see a world may rise as golden as Blake

Knew in his winged dreams, and the leaves of good

Burst out on branches dead from winter’s hurt.

Then the lame may rise and the silent voices speak.

Finally, here is a poem I wrote for (and read at) the Woodcock centenary (note that Woodcock was a friend of Orwell’s, and wrote a full-length study of him as well). I will note as well — in terms of context and community — that a number of activists with whom I currently organize were arrested and roughly treated by the Vancouver police shortly after I wrote this poem, and that I subsequently read it at a rally in their support. I wrote the poem with Woodcock’s “aesthetic” “choice” in the forefront of my mind, with every intention of being as blatantly “political” as I could be. Let it stand as a foray into my own “diversity of aesthetic tactics.” Context, community, solidarity, and struggle do, in the end, make a difference.

Orwell on Facebook

It’s when we wake up

To realize we are not free —Endless links to YouTube videos

Of the police beating peopleSome banker types claiming

They are representative, electThrowing everything — rivers

Lakes every animal on landAnd sea and love itself on the fire

Of their endlessly accumulating wealth —It’s only then that we at last face

The real threshold of our lives:Will we “Like” what’s actually on offer

Or bite down hard on the boot in our face?

Neighbouring zones