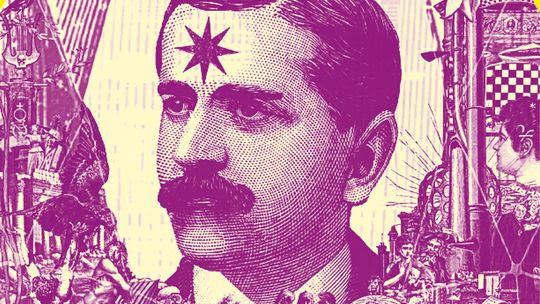

Fous Littéraires: Some examples from a non-cannon — No. 3

Raymond Roussel (1877–1933): Part 1 — Life and influences

Rich, gay, habitually solitary and a cross-dresser, or better, simply an inveterate dresser-(upper), Raymond Roussel is, along with Antonin Artaud, by far the most well-known fou, if not necessarily its most beloved, at least not by those who consider themselves serious students of the genre. That honor I would argue goes to Jean-Pierre Brisset, of whom more later.

Roussel as a boy Roussel as a man

Roussel as a chambermaid Roussel as a...

(https://strangeflowers.wordpress.com/2011/01/28/dress-down-friday-raymon...)

Born into the Parisian beau monde, as a child Roussel had Proust for a neighbour. As an adult, he befriended Cocteau in rehab. When travelling abroad he used a private custom made car with its own miniature suite of rooms; Roussel may possibly be considered the inventor of the RV.

Roussel's travel car, images from a postcard

He was a prolific writer, penning numerous novels, often in verse, including La Doublure, Locus Solus, and Impressions d'Afrique (Impressions of Africa), later turned into a theatrical piece, as well as plays, and the Nouvelles Impressions d'Afrique (New Impressions of Africa)–a poem of four cantos with 59 drawings. While different from each other, each of these works appears as a "succession of mind-curlingly complicated, nonsensical, self-referential events, a closed world adhering to its own internal logic where tortures, ecstasies, trifles and miracles are all served up in the same crisp, affectless prose," (James J. Conway, https://strangeflowers.wordpress.com/2012/01/21/locus-solus-impresiones-de-raymond-roussel/).

The utterly unique and bizzare nature of these works meant that during his life his work was ignored by all but a handful of the avant-garde, who adored him. André Breton named Roussel, along with Lautréamont, " the greatest magnetizer of modern times,” Marcel Duchamp, called him “he who points the way”, (ibid.). Dali also worshiped him, creating a film, Impressions de la Haute Mongolie (subtitled Hommage à Raymond Roussel), in which he "works through his unrestrained hero worship," (ibid.). But Roussel's greatest impact seems to have been on Duchamp, who acknowledged his work as the inspiration for The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even. "Even Duchamp’s premature abandonment of art for chess was apparently inspired by witnessing Roussel playing the game in a Paris café," (ibid.). In 1962 John Ashbery, Harry Mathews, James Schuyler and Kenneth Koch founded a literary journal named Locus Solus after Roussel’s novel, and the following year Foucault wrote a book-length study that ignited scholarly interest in his work. Since then Deleuze and others have continued the legacy.

Recently, numerous visual exhibitions have been devoted to both his life and his influence. For instance, Locus Solus: Impressions of Raymond Roussel, held in 2012 at Madrid’s Museo Reina Sofia, featured not only personal artifacts such as his beloved star cookie enshrined in a glass box,

Roussel's cookie

but also works by contemporary artists based on his writing:

"Jacques Carelman’s large-scale 1975 installation Le Diamant is a rock-mounted prism enclosing a freakish assortment of figures and objects, moving by mechanical means,... rendering a descriptive passage in Roussel’s Locus Solus as literally as possible," (ibid.).

Other artists featured include Zoe Beloff, Lucy McKenzie and Henrik Olesen, whilst the show's catalogue is a great introduction to the life, work, influence of, and critical writing about the man and his work.

Interestingly, Locus Solus illustrates how surprisingly conventional Roussel’s tastes were.... When Roussel wanted his works illustrated, he ignored the Surrealist artists who craved his patronage and turned instead to stolid academician Henri-Achille Zo, (although in Roussel’s typically eccentric fashion he used a detective agency as an intermediary), (ibid.).

The writer shunned Breton and cohort because, while grateful for their interest, he felt little kinship.

The Surrealists might have detected an unmediated transcription from an unfathomable and unfathomably disordered mind, but as [the] manuscripts [in the Reina Sofia exhibition] show, Roussel was in fact a fastidious self-editor. His work is unquestionably bizarre, but it was not driven by the Surrealists’ desire to disrupt reason and foment revolution, nor was it a despairing Kafkaesque amplification of everyday absurdity, (ibid.).

A page from the ms. of Locus Solus

Likewise, Roussel did not aim to provoke his audience, as did the Surrealists, along with Jarry and Artuad. Neither was he interested in, "psychological investigation, philosophical enquiry, humorous diversion, momentary escapism, spiritual uplift, moral instruction, [or] sentimental reflection," (ibid.).

Nevertheless, there is method in Roussel’s madness, revealed by the posthumously published essay, How I Wrote Certain of My Books, which may, as its title suggests, be seen as the "key" to his work. Here Roussel details the "devices" used to construct his works. More perhaps than the forms and contents they produce, these devices and their attendant methods of construction are the focus of interest for scholars of the fou, for these reveal an attitude to, and an engagement with language quite different from those normally assumed by both writers and linguists. To these we shall now turn.

Fous Littéraires: Mad linguists and other literary fools