Fous Littéraires: Counter-examples preliminary to a non-cannon

What is a fou? Or, whose work counts in the non-cannon?

Despite the catalogues and encyclopedias, almost by definition there can be no fou cannon. Not only is the study in its infancy, basic criteria are hard to establish. On the surface the Victorian Nonsense of Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll might be considered, but for reasons that will become clear later, though related, Nonsense is not generally included. Another candidate might be the private anagrammatic investigations of the esteemed linguist Ferdinand de Saussure who, during the same years–1906-1910–that he worked on his influential (some would now say pernicious) "science" of signs, he also spent copious time searching for anagrams in a variety of texts, from the Rig Veda to the Niebelungen. These special poetic words, Saussure believed, were the explanatory keys, or pre-texts accounting for each work's origin, and at least part of its meaning, (see Philosophy Through the Looking Glass, Jean-Jacques Lecercle, 1985). The problem with this method, as every practitioner knows, is that virtually any pre-text can be found in any text. It is therefore functionally useless, even if, or especially when pursued obsessively. Though Saussure himself was obsessed, he was also far too much the scientist to let his private compulsions become public statements.

A more promising line might then be sought amongst the speakers of tongues, or glossolalialists. Glossolalia "is the fluid vocalizing of speech-like syllables that lack any readily comprehended meaning, in some cases as part of religious practice in which it is believed to be a divine language unknown to the speaker," (A Dictionary of Psychology, Oxford University Press, 2009). The practice has been discussed since biblical times, when St. Paul sought to circumscribe the conditions for its use. St. Patrick of Ireland is said to have heard strange languages spoken in his dreams, and Hildergard of Bingen is reputed to have spoken and sung in tongues. Over the centuries many Christians groups like the Camisards and Quakers also practiced speaking in tongues as an experience of "Spirit baptism," (see The great mystery of the great whore unfolded; and Antichrist's kingdom revealed unto destruction. The Works of George Fox, 1831). During the 20th century, glossolalia became associated with Pentecostalism and the later charismatic movement, founded by the African American preacher William Seymour and the white Evangelist Charles Parham. In 1900 Parham opened a bible college in Topeka Kansas, where a student named Agnes Ozman experienced glossolalia in the first hours of the 20th century. In 1906 Seymour moved to Los Angeles where his words ignited the Azusa Street Revival, considered the birth of the global Pentecostal movement, in which glossolalia played an important part until its demise in 1915, (see The Charismatic Movement, Michael Pollock Hamilton, 1975).

None of this of course was written down, let alone published, one reason for its non-inclusion in fou bibliographies.

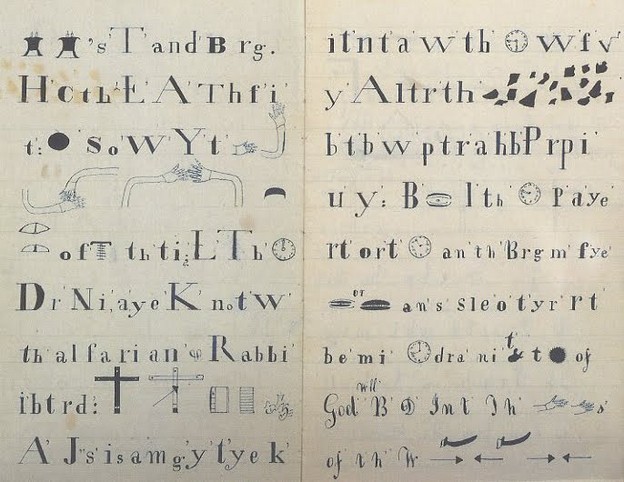

Not so however the work of the 19th century medium Hélene Smith, or that of the Gift Songs produced by young Shaker women in the 1840s. In both cases young women transcribed onto paper messages they received from beyond; Smith, from spirits she encountered in trances at séances, the Shakers, from God. Smith's spirits spoke to her in a bewildering variety of tongues, from ancient Sanskrit to Martian, and the even more esoteric Ultra-Martian. Shaker women received God's songs as visions, which were sometimes communicated to one girl, who described them to another who wrote/drew them down in pen and colored ink to form delicate tableaux that mix the highest geometrical abstraction with the sensibilities of the primer and the sampler, (see "Speaking Martian," Daniel Rosenberg, Cabinet No. 1; and Heavenly Visions: Shaker Gift Drawings and Gift Songs, Uni. Minnesota Press, 2001).

Helene Smith, Martian Script Shaker Gift Song-Drawing

Neither of these however is included in the non-cannon of the fou. Why? Jean-Jacques Lecercle, an expert who has written numerous books on the topic–the only overall introductions to the subject in English–believes that Smith's work lacks a real interest in language, and that the fact that she produced her writings in trance, where she became the incarnation of a Martian lady or the wife of an ancient Indian Prince, somehow renders it less interesting, or at least less compelling to the eccentricologist. Given the mental states under which many recognized fou produce their work–Schreber believed he channeled God's rays, and Brisset was the sometime mouthpiece of the Seventh Angel–it is hard, aside from prejudice, to see why this work should be dismissed. The true fous may not be a mere medium, but mediumship is often an essential component of their methods. We are reminded again of Susannah Wilson's observation about the perception of femininity in this regard. It is as though work by women cannot be seen as "outsiderish," precisely because femininity itself is already a form of outsidership or otherness; and as we know, there is no other of the other.

For now, we shall bracket this question and look at a few examples of recognized fous.

Fous Littéraires: Mad linguists and other literary fools