Digital Poetics 2

Not your father’s confessionalism

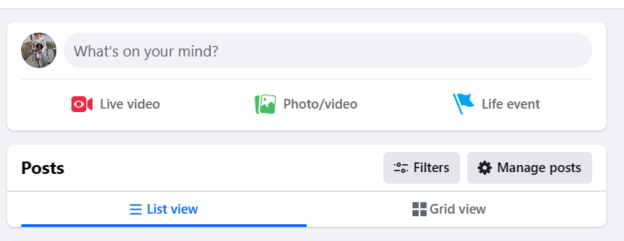

A blank text field. Oblong. With rounded corners. It is our refuge where we are free to say almost anything. Some treat it as a mail slot to dispatch their most personal thoughts. Others leap across it as a stage where they become a different person. Or a heaving jumble of Pessoa-like heteronyms, or what most people call trolls. Most of us troll without noticing, or we perform for clicks with a keen understanding that what we type (however non-factual) conjures data about what we are. An armchair existentialist might say the space mirrors the void inside us. And a social theorist might pinch the same view, while citing the latest statistics about the atomization of culture. Such theories are fine, fine the way hot coffee is fine — unless they forget the field itself.

In our first essay, we talked about the death of the analogue self in poetry. This time around, I want to focus on the spaces where the 21st-century self confesses itself. The Facebook status message. The Twitter/X update. The comment area of an Instagram post. They vary by shape and character-limit, but they remind the lapsed Catholic in me of the “Confessional.”

With the plaid uniform I wore for the nuns, I only knew “confessional” as a noun. It was the wooden box in the corner of the church where the priest listened to our sins behind a screen. The arrangement was discreet. Priest in the center box the size of a phone booth, a compartment on both sides. Crosses carved into the screen. They were a visual reminder of what many of us later heard from therapists: “I cannot promise to treat you if you don’t tell me the truth.” Whatever the transgression, telling the truth and mumbling those three “Our Fathers” and four “Hail Marys” were the only way to be forgiven. In retrospect, it wasn’t a bad deal. We could do every foul thing and get away with it like a Wall Street banker buttoning his Brioni in front of the courthouse.

“Confessional” as an adjective arrived later, during my “DIE Yuppie Scum” sophomore year at NYU. With regular sightings of Ginsberg and Corso around the Village, “Introduction to 20th-Century British and American Poetry” folded nicely into my backpack. The course was taught by M.L. Rosenthal, a poet and critic who had coined the term “Confessional Poetry” almost twenty years prior, in a review of Robert Lowell in The Nation. In a lecture for the final section of the semester, which encompassed Plath, Lowell, Ginsberg, O’Hara, and Sexton, Rosenthal uncorked the “confessional” as being “on the psychiatrist’s couch” talking about “a shame we felt, or a sin.” The term slotted nicely against the Brahmin self-loathing of Lowell’s Life Studies and the fisted strophes of Ginsberg’s “Kaddish.” But when we thumbed the other poets, and even other poems from Ginsberg, the term rode up on the guts like the shocks on a 1975 Mazda.

The chuff, the rumble told me something I didn’t understand until I belted up Dockers every day. Literary critics are the branding specialists of literature. They Don Draper new terms, then staple them to every sentence that crosses their path. For instance, what’s “confessional” about “Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m though”? Plath is not confessing. She is drama queen in full meltdown mode. We see her in the coming attractions of the next episode of her reality TV show or as the talk-bubble of a comic strip sampled by Roy Lichtenstein.

Or what about the Ginsberg of “Howl”? His generational cast-offs:

who bit detectives in the neck and shrieked with delight in policecars for committing no crime but their own wild cooking pederasty and intoxication,

who howled on their knees in the subway and were dragged off the roof waving genitals and manuscripts,

who let themselves be fucked in the ass by saintly motorcyclists, and screamed with joy…

Ginsberg is a dirty standup comedian here—personal, yes, but also playing for laughs and for shock. Like Plath, there is truth-telling without the sadness or dragged feet of the remorseful. Both poets are too deft, too willful, for the one-to-one relationship with experience that “confessional” implies. Let’s not let decades of fanboys, fangirls and haters obscure the obvious. Plath and Ginsberg are persona poets who have made themselves their chief subject.

Twenty-first-century poets draw from the example of these poets, with varying degrees of digital engagement. For Patricia Lockwood, engagement has meant adapting the immediacy of social media, along with the cultural codes of online communities:

“Rape Joke” (from Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals, Penguin Books, 2014)

The rape joke is that he was seven years older. The rape joke is that you had known him for years, since you were too young to be interesting to him. You liked that use of the word interesting, as if you were a piece of knowledge that someone could be desperate to acquire, to assimilate, and to spit back out in different form through his goateed mouth.

Then suddenly you were older, but not very old at all.

The rape joke is that you had been drinking wine coolers. Wine coolers! Who drinks wine coolers? People who get raped, according to the rape joke.

While Lockwood is known today as a novelist, memoirist, and essayist, “Rape Poem” pushed her into everyone’s news feed. The poem was published in 2013 in The Awl, a beloved (and sadly now-defunct) online literary journal, but instead of getting a few likes from the poet’s friends and dissolving into our browser history, it was shared and reshared on Twitter, Facebook, Reddit, and Instagram with the enthusiasm usually reserved for a hit song or cat video. Stories in The New York Times, The Guardian, and other major news outlets followed. The popularity of the poem prefigured the #MeToo movement by several years. Women bounced off the anaphora of the lines to tell their own stories, often with a meme-like repetition of the poem’s dark humor.

Among young poets, especially those from Black, Queer, and Native communities, engagement with the digital is even more direct. Their experiences are declared loudly, with none of the shame that dragged behind the pre-Civil Rights, pre-Stonewall, pre-feminist “confessional.” Their poems edge toward the all-lower-case with a run-on immediacy that feels like a late-night text message. Many extend active online presences with hundreds of thousands of followers, dispersed between Twitter/X.com and Instagram accounts:

“The 17-Year-Old & the Gay Bar” (Danez Smith, courtesy of The Poetry Foundation)

this gin-heavy heaven, blessed ground to think gay & mean we.

bless the fake id & the bouncer who knew

this need to be needed, to belong, to know how

a man taste full on vodka & free of sin. i know not which god to pray to.

i look to christ, i look to every mouth on the dance floor, i order

a whiskey coke, name it the blood of my new savior.

With Smith, technology has brought a vitality to poetics which often goes overlooked. What we now call “social media” was once known as “online community.” The belief, from the early days of online, was that the Internet was a Global Electronic Village that dissolved geographic boundaries to bring people together.

If this concept hits like reheated hippie-talk, that’s because online culture today is too often about tribalism, or the self-exclusion of groups. The Global Village has become a private treehouse, where an in-group affirms its purpose by defenestrating non-believers from its ranks. The behavior has pushed beyond the limits of the virtual, impacting our politics and our social relations. The ability to filter whom we talk to online has become the “ghosting” of people in our everyday life. Even the term “canceled” partakes of this instrumentalism. It implies that people are services we can discontinue when they become troublesome or no longer appealing.

When I started out in the online business, working on the bulletin boards for Prodigy’s dial-up service, there were petabytes of negativity. But, like the technology itself, it was localized on our network, it didn’t touch the global immediacy of Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or TikTok. Nor was it a substitute for the real world or place to share “Instagrammable moments” from our day.

Curling a fist against the productizing of the human takes many forms. Among the most hateful is the troll. The troll is the person who uses the tools of their age to affirm the imagined authenticity of what went before. If Caligula invented trolling when he made his horse a senator (and announced it on the scrolls—the Twitter of Imperial Rome), Pound was the troll king of Modernism and Frederic Seidel is its current poet laureate. His decades of performative negativity and odes to Ducati motorcycles and bedding much-younger women are notorious. The edgelord persona behind them, though analogue, seems nonetheless optimized for viral popularity on Truth Social and white aggrievement subreddits. Critics who go out of their way to defend his antics as Byronic flexing miss the joke. Seidel cares about not caring. Our disapproval sweetens his joy:

“Widening Income Inequality” (from Frederick Seidel Selected Poems, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020)

I live a life of appetite and, yes, that's right,

I live a life of privilege in New York,

Eating buttered toast in bed with cunty fingers on Sunday morning.

Say that again?

I have a rule—

I never give to beggars in the street who hold their hands out.

Seidel is not alone in his versified trolling. A new generation has risen to offend and delight. For them, the online and poetic “I” is the delivery mechanism of a different kind of confessionalism. Their “self” is a parody of the engaged poetic citizen. The truth they serve is the contrarian, the skeptical, the community-of-one. There are several names I could toss in here, but I’m not going to. I refuse to give these folks more attention than they have already received on Fox News. I would rather shout out other poets who have integrated the digital into their voice for more positive reasons.

One is Diane Seuss. frank: sonnets (Graywolf, 2021), which won the Pulitzer Prize, is the “confessional” unleashed on the newsfeed. Experiences, names, dates, influences, memories all scroll past with the details of a life skinning its textures:

“[I met a man a dying man]” (from frank: sonnets, Graywolf, 2021)

I met a man a dying man and I said me too.

Met a dead man and I said me too. Must be

dead cuz the living can’t meet the dead and he

said me too. Did you know the dead can fall

in love he said. Fact. Did you know the dead

fall in love better than the living cuz nothing

left to lose. The root of all blues. Skeptical still

I strode onward in my seven-league boots as in

the fairy tale “Hop-o’-My-Thumb” from a book

of German fairy tales given to me when I had

chicken pox. Scratching myself bloody, the ogre

gored to death by wild beasts. Seven leagues per

stride toward a dead banjo player in a bad

mood. Enchanteur. Or zauberhaft in German.

The wildness of the verse is difficult to reproduce. In print, the lines often disappear into a fold-out the way a late-Coltrane solo locates spaces between, above, and around traditional chords. The collection’s title is both a statement of its all-in aesthetic and a tribute to its New York School forebear, who likewise chronicled their emotional and physical wanderings. For Seuss, it’s less about O’Hara’s “I-do-this-I-do-that” serialism than a simultaneity of experience as a working-class artist zipping between sensation and painful recollection. The poet isn’t asking for opinion or offering hers. She wants us to feel the underside, with a single exposed finger.

Seuss’s touch doesn’t stop at the page. She extends her hand into the everyday life of online community. While other lauded poets only post photos of themselves at prestigious universities in the clutch of the equally lauded, Seuss is the Whitmanian poet as Facebook friend. One night finds her liking an obscure Ramones concert from 1982, then boosting the work of a new poet.

It doesn’t seem possible to talk about poetry these days without accounting for the online persona that shoulders its arrival. Seuss and Smith are only two examples. Almost any poet we can mention, like most people, lives online. The result is a poetics that leans toward the camera, duck-faced for its selfie. It’s an act which shines the poet’s “brand” while giving the social network more data to monetize.

How do we reconcile the contradiction, the absurdity? We don’t. We keep on living, like Warhols mining our own upper dermis. And we hope to avoid getting torn to pieces by online gangs or write poems that lean into a clean, agreed-upon “position.” Poetry, as any art, is not about the “likes,” it’s about cupping that ambiguous, uncomfortable feeling.

Digital Poetics