'grasses' meet 'monster owl': On the UC Davis Satellite Event with Jonathan Skinner and Brian Teare

by Gillian Osborne

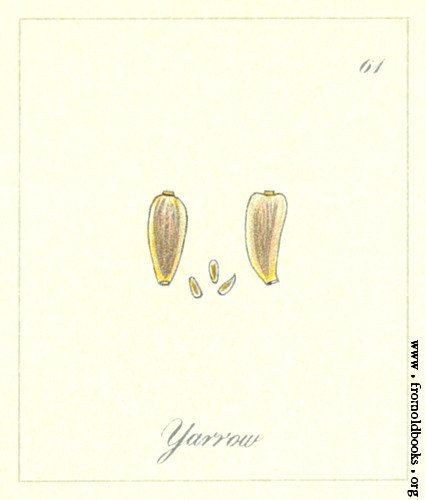

In the UC Davis Arboretum, common yarrow (Achillea millefolium), a “companion” plant, has many uses and many names. Along a sculpted river topped with scum, warblers disappear and reappear in native and non-native shrubs and branches. Brian Teare and Jonathan Skinner are talking about ecopoetics: the poems of Ofelia Zepeda, “emergency,” and Lee Edelman’s No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. We stop to smell the sages and the yellow puffs of acacia.

The 2013 Conference on Ecopoetics began at a satellite event hosted by the Davis Humanities Center. Jonathan Skinner, editor of the journal ecopoetics, and author of among other books, Warblers, published by Brian Teare's micro-press Albion Books, sat at a table with his publisher and fellow-poet, whose most recent collection, Companion Grasses, will appear in print April 1. A selection of this same volume, “Transcendental Grammar Crown,” can also be found in the newly released Arcadia Project, edited by Joshua Corey and G.C. Waldrep.

Skinner and Teare read from these and other poetic projects; and they presented portions of position papers they would give during the conference itself. You can find an edited version of Skinner’s paper, which he delivered on Friday at the conference’s Advisory Board Roundtable “What is Ecopoetics?” here. (Check back for a link to an audio recording of this full session, which also included statements by Forrest Gander, Robert Hass, Brenda Hillman, Lynn Keller, and Michael Ziser).

While Skinner’s talk at Davis provided a overview of how the theorization of ecopoetics has evolved over the last thirty years—from works like Michael McClure’s Scratching the Beat Surface (1982) or Gary Snyder’s The Practice of the Wild (1990) to more recent critical projects like Jed Rasula’s This Compost (2002) and the ecolanguage reader (2010) edited by Brenda Ijima—Teare directed his paper toward questions about a “poethics” of “care”: how does our language care for the world without “taking care of it,” a phrase which, as Teare pointed out, can mean both tending to or doing away with, as in take care of this ailing animal by shooting it.

Teare talked about the enormous “pressure” placed on ecopoets to get it right, both because the stakes are so high, and because the medium in which they deal (language!) is necessarily muddled and slippery. His assertion that ecopoetics needs to embrace these inherent slippages of language resonates with Skinner’s idea of ecopoetics as a “boundary” site, a point of intersection and even interruption between habitats, an “ecotone,” which, he reminds us, designates not a “tone” but an edge. Skinner also encouraged a shift in thinking about the state of the environment from “crisis” to “emergency.” The difference being that “emergency” leaves room for the “emergence” of new forms—both biological and creative.

That was the reporting bit. Now for a little digressive reflection, spinning off at an angle. At one point in their conversation, Teare referred to a poem from Lorine Niedecker’s New Goose (1945) (p. 105 of Niedecker’s Collected Works):

Asa Gray wrote Increase Lapham:

pay particular attention

to my pets, the grasses.

Asa Gray taught botany during the later half of the nineteenth century at Harvard; the Gray Herbarium houses his enormous dried plant collection at the same institution today. And Increase Lapham was one of Wisconsin’s (Niedecker’s home state) foremost naturalists. (Check out this incredible image of him seriously consulting a meteorite).

Teare brought this poem up to explain his own interest in relating to grasses as “companion species” rather than “pets," beings necessarily subjected to the care or mistreatment of their keepers. In contrast, companion plants operate in symbiosis with their environment, attracting or repelling particular insects whose behaviors—predatory or pollinating—are beneficial to the species, or by contributing or storing particular nutrients that may support the flourishing of other plants. The particular companionability of plants is something farmers can plan their fields around—planting nitrogen fixing beans alongside corn, for example, or mosquito ferns in rice paddies. But it’s also a way in which plants direct the contours of their own environments, regardless of human desires or concerns. (For more on plant “intelligence and attention” see Michael Marder’s website, with links to or pdfs of many of his articles; or check out his brand new book, Plant Thinking: A Philosophy of Vegetal Life).

According to Jenny Penberthy, the editor of Niedecker’s Collected Works, the poet sent a longer version of this clipped poem to Louis Zukofsky in a letter (p. 376):

Great grass! The shoots Michaux

brought back to Philadelphia

by way of Bartram and known to Linné

bear Jefferson’s name.

Asa Gray wrote Increase Lapham:

pay particular attention

to my pets, the grasses—

on these lie fame.

Here, the two naturalists extend into a full litany of impressive 18th and 19th century names, while the declamatory “Great grass!,” the concluding statement “on these lie fame,” and the one resounding rhyme in the poem between "name" and "fame," neither of which survive into Niedecker's final version, make what feels like bemused affection in the shorter poem—say hello to my little friends the grasses—into a more explicit connection between “attention” to (notoriously difficult to correctly identify) grasses and the elevation of naturalist careers. In other words, the longer poem makes the “pets” of the shorter poem, which Teare was already uneasy with, seem even more ominous: these grasses are here for your exclusive benefit, Oh men of science. Attend to them!

What distinguishes the “attention” that Gray instructs Lapham to “pay” to the grasses from the form of “attention” that ecopoetics hopes to cultivate? Joshua Corey concludes his introduction to the Arcadia Project with a call for poetry as an act of attention: “If it is not to be altogether delusional and vain, an anthology such as this one must be a living and motile assemblage of our best hopes for what poems can be: vessels of attention to the world and to language, attention at its most intense. To be present, with/in the world, with/in words, in active relation to the living (and dying) environment—that is the ordinary utopianism practiced by these extraordinary poems” (p. xxiii). (More reporting: Corey discussed this anthology during the conference as part of a panel, "Editing the Book of Nature," on recent anthologies of ecopoetics; co-presenting with him were Camille Dungy, editor of Black Nature, and Ann Fisher-Wirth and Laura Gray-Street, editors of the Ecopoetry Anthology.)

“Attention at its most intense.” Both to world and to language. Could this acute attention convert us into companion species? Relieve grasses from being our pets and elevate any affection we feel for them into a form of attending? (What forms of nitrogen might poems fix?) Ecopoetics is necessarily utopic, even at its most humble (“If it is not to be altogether delusional and vain”); states of “emergency” require it.

But the attention that ecopoetics pays is also an attention to alterity, to ways in which grasses resist us and our forms of attention. In “What is Experimental Poetry and Why Do We Need It?” Joan Retallack advocates for a “reciprocal alterity,” an application of contemporary poetry’s wildnesses to other wilds, a simultaneous unreckoning, a wrecking that is both shocking and pleasurable. These practices are “poethical,” by which Retallack means, “questing to know what can be known only by means of poetry, approaching what is radically unknowable prior to the poetic project, acting in an interrogative mode that attempts to invite extra-textual experience into the poetics somehow on its terms, terms other than those dictated by egoistic desires.”

Return to these grasses a bird. (Skinner in conversation with Teare.) Not a song bird, but a creature that speaks nonetheless. In another poem from New Goose (Collected Works p. 103), Niedecker spots a “monster owl.”

A monster owl

out on the fence

flew away. What

is it the sign

of? The sign of

an owl.

Niedecker’s owl takes off from an Emersonian fencepost, the tripartite definition of nature Emerson gives in Nature (1836) (an equation that Teare also referred to in his talk): “1. Words are signs of natural facts. 2. Particular natural facts are symbols of particular spiritual facts. 3. Nature is the symbol of the spirit.” Here, the owl is not a sign but a monster. Not a monster but an owl. A sign of a sign. An owl an owl. Alterity leaves behind fences and flies in and out of the poem.

I referred at the beginning to the many common names of Achillea Millefolium. Among these, “blood-wort,” “woundwort.” It is known to staunch bleeding, soothe infections, and support the reproductive organs of women. It has appeared in legend: Achilles carried it to the battlefield and attempted to correct his draining heal. The beneficial distances of a “common” plant, sprouting in “waste” places through much of the northern hemisphere. This growth that is a stranger and a balm.

Field notes from the 2013 Conference on Ecopoetics