Ezra Pound, Canto III

LISTEN TO THE SHOW

This time PoemTalk took on Canto III of Ezra Pound’s epic, The Cantos. For such a daunting task we gathered Kaplan Harris (who came from far-western New York State for the occasion), Richard Sieburth (the brilliant NYU Poundian, who interrupted a sabbatical to lend a hand), and Philadelphia’s own (and, originally, Brooklyn’s own) Rachel Blau DuPlessis.

This time PoemTalk took on Canto III of Ezra Pound’s epic, The Cantos. For such a daunting task we gathered Kaplan Harris (who came from far-western New York State for the occasion), Richard Sieburth (the brilliant NYU Poundian, who interrupted a sabbatical to lend a hand), and Philadelphia’s own (and, originally, Brooklyn’s own) Rachel Blau DuPlessis.

We began by considering what Al – for lack (at the moment) of a better word – calls the four or five “blocks” of topical segments that Pound typically brings together in a collage of historical materials and genres. We work through these, explore the associations, and find our way back to Pound himself (presented in the first “I” of The Cantos), remembering himself young, penniless, ambitious, shut out of rightful civic entry – like The Cid, a hero of this poem; and perhaps, too, like (but also unlike) Robert Browning (who makes a slant appearance).

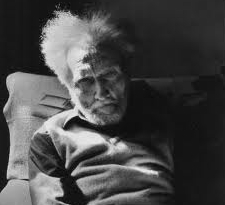

The third canto was drafted around 1917 and published between hard covers in 1924-25. Although Pound recorded several performances of other cantos through the years, he did not record this poem until the summer of 1967, when he was 81. The voice you hear in the PennSound recording is frail, although Kaplan and Richard both remind us that Pound is, even here, putting on the performance of weak retrospection (a specialty, as a matter of tone and also content, of the final cantos which he had been writing not long before this). What is remarkable is that the poem contains a memory already (when it was written) of a very early moment for the poet (1908), and now, nearly sixty years later, we hear the old poet remembering the memory. There are moments – words re-uttered – when he certainly comes alive through emphasis and what one might call “deep memory.”

We urge you to listen hard for Rachel’s terrific riff on the importance of Pound’s deployment of the “genre circus,” and of Pound’s late “my notes do not cohere” problem. “Notes” in themselves, are one of the many genres deployed, says Rachel.

We urge you to listen hard for Rachel’s terrific riff on the importance of Pound’s deployment of the “genre circus,” and of Pound’s late “my notes do not cohere” problem. “Notes” in themselves, are one of the many genres deployed, says Rachel.

And listen all the way to the end here, folks. In his “final word,” Richard treats us to a marvelous description of the role played in Pound’s complex conception of the poem by the hyper-desired figure of Inez de Castro, lover and posthumously exhumed and declared wife of King Pedro I of Portugal (in the 1350s). At left: Inez de Castro.

Richard Sieburth is also the author of “The Sound of Pound: A Listener’s Guide,” which is the most authoritative account of the recorded voice of the important modernist. The essay was written for PennSound and is linked from PennSound’s Pound page. Just to be clear: PennSound’s Pound page includes every recording of Pound reading his poetry that we know exists. As you will see from the credit lines and acknowledgments on that page, we depended on the kindness of many people to produce such a collection.

March 15, 2011

Borges off Pound

In December of 1921, a 22-year-old Jorge Luis Borges published “Ultraísmo” in the Argentine journal Nosotros. The editors wrote that his short article was the initial entry in a series of studies about the avant-gardes,[1] recognizing perhaps that the moment of the ultraísta movement had already passed (a few months later, the key journal Ultra ceased publication). While the avant-garde principles of ultraísmo would continue to inform the work of many poets both Spanish and Latin American, by 1921 the movement qua movement was drawing still. But for the literary establishment, understanding ultraísmo was just beginning, and thus Borges’s essay was an attempt to assert the new literary ethic through accounting, a manifesto in reverse.