Reading by Don Mee Choi

'My tongue, your tongue is already an aggregate.'

About sixty people gathered in Bennington College’s Tishman Lecture Hall on the evening of November 28, 2018 for Don Mee Choi’s reading for the Poetry at Bennington series, mostly professors, students, and local artists and poets including Mary Ruefle and the painter and collagist Mary Lum. The series curator, Michael Dumanis, introduced Don Mee warmly before she took the podium, wearing a white paper hanbok, or traditional Korean dress, that she had made herself.

The lighting in the high-, wooden-beamed-ceilinged hall was low and cozy to accomodate the projection of images on a large screen above a long blackboard behind Don Mee, who read from two recent books: her second full-length poetry collection, Hardly War, and her translation of eminent Korean poet Kim Hyesoon’s Autobiography of Death. Don Mee read first from the latter, mentioning that she has been translating Kim Hyesoon’s poetry for eighteen years. Don Mee has translated ten collections of poetry from Korean and is currently working on a prose translation. In a craft talk with students earlier in her visit, Don Mee emphasized the capacity of translation as an anti-neocolonial mode that can “disrupt and throw off the expectations of history.”

Autobiography of Death is Don Mee’s sixth translation of Kim’s writing, and she described Kim’s work as poems that “house mothers with motherless tongues.” Autobiography of Death comprises forty-nine poems, each representing a day. In introducing this part of the reading, Don Mee noted that in Korean Buddhism, there is a belief that a person’s spirit wanders for forty-nine days after death before reincarnation. Kim's collection explores death as an individual and collective process intimately imbued with issues of power.

Kim Hyesoon’s daughter, Fi Jae Lee, illustrated the collection with unsettling unbroken-line drawings that she’d made every morning. The book’s cover image projected above the podium featuring a blindfolded woman writing in a hospital bed, hooked to an IV full of blood with a severed umbilical cord and insects buzzing around her, her mouth open. Don Mee began by reading the collection’s second poem, “Calendar: Day Two,” animated by surrealistic dying ant-rabbits, following that poem with a reading of “I Want to Go to the Island: Day Twenty,” which references the 2014 Sewol ferry disaster in which hundreds of people died, most of them high-school students, an event that endures in Korean society as a senseless tragedy and hallmark of corruption. A section from the middle of the poem reads:

You head to the cafeteria to shake off your ominous thoughts.

You might have heard the ship floating on black water sobbing sadly.

You receive a phone call after midnight.

The call’s about the emptiness of your being gone.

This is the thousandth call.

But emptiness over there is transmitted to you in spite of the calls.

You go into the hallway and pick up the receiver and sing the oldest song you know into it.

You set a time for your song to be sent.

So someone feeling empty can hear the song as soon as she opens her eyes the next morning.

Don Mee read in Korean and English in a steady, lilting voice, rhythmic and emphatic in a quietly authoritative manner. After reading a few more poems from Kim’s book, Don Mee moved to the center of the stage, holding a large mic and exposing the full skirt of the paper hanbok. A student tech adjusted the projector to project on two screens: the original one on the wall above the stage and a second smaller screen behind Don Mee, which her figure blocked, so that the lower image splayed out against the dress, her body casting a human-shaped shadow onto the small screen with her face in half-shadow.

A striking photograph of civilians climbing across a bridge taken in 1950 by Max Desfor, titled Flight of Refugees Across Wrecked Bridge in Korea, opened the sequence of photos from Hardly War, most of which were taken by Don Mee’s father, who was a photographic journalist during the Korean and Vietnam Wars. Hardly War integrates these artifacts from wartime photography with a text that combines verse, memoir, historical fact and distortions, and opera to interrogate how these wars are represented and their persistent effects on the civilians living through them. In a Q&A earlier in the day, Don Mee had noted that none of the photographs in Hardly War depict battle, quoting Roland Barthes’s belief that “photography is most subversive when it is pensive, not when it repels.” She pointed out that 2018 marks the 73rd anniversary of Korea's division with both sides, abetted by US and other forces, still technically at war, as no peace treaty has ever been signed.

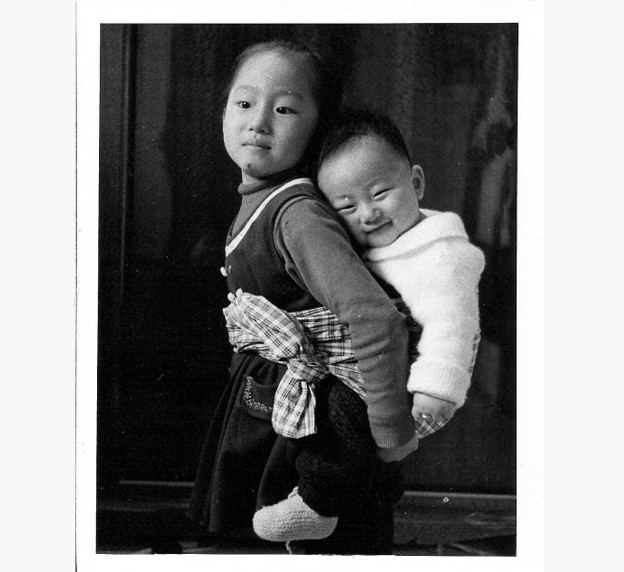

As the photograph of a young girl carrying her baby brother in front of a tank was projected above, on, and around Don Mee, she read the poems “A Little Glossary” and “Woe Are You?” which allude to the dropping of DDT and napalm by the US during the Korean and Vietnam Wars, following these with a a reading of “A Little Menu,” which catalogues industrial food items imported from the US to South Korea. The projected image shifted to her father’s 1948 photograph of the Republic of Korea’s first President Syngman Rhee, General MacArthur, and General Hodge, the figures’ faces crinkling and stretching and shadowed by the creases on Don Mee’s dress, suggesting how every lens and screen distorts and bends previous iterations and how a single person and body can affect historical representation.

Don Mee read at a precise pace from loose sheets of paper rather than her bound book, dropping pages on the floor as she read. She concluded by reading from the third section of her book, “Hardly Opera,” which combines interviews with her father, historical record, imagined scenarios, and song in a surrealistic fantasy animated by the voices of flowers that underscores the indecipherability of trauma in spite of multiple efforts, sincere and obfuscatory. Before that, Don Mee read her poem “Operation Punctum” in conjunction with a video loop of soldiers pushing helicopters into the sea, as a BBC reporter comments, during the last chapter of US involvement in Vietnam, the helicopters bouncing and shaking menacingly on land before being tumbled into the waters. During the reading of this poem, Don Mee’s steady, quiet voice drowned out the reporter’s official commentary. As the reading concluded, the video clip projected silently, the poet enacting the last heard word.

Tweens: Asian American Poetry & Poetics in the 2010s