Lawson, Henry (See: Lawson, Louisa)

Every eccentricity of belief, and every variety of bias in mankind allies itself with a printing-machine, and gets its singularities bruited about in type, but where is the printing ink champion of mankind's better half? There has hitherto been no trumpet through which the concentrated voices of womankind could publish their grievances and their opinions. Men legislate on divorce, on hours of labour, and many another question intimately affecting women, but neither ask nor know the wishes of those whose lives and happiness are most concerned. (Louisa Lawson, The Dawn, May 1888)

ASSOCIATED LABOUR seems to be in its own small way just as selfish and dictatorial as associated capital. The strength which comes of union has made labour strong enough, not only to demand its rights but strong enough also to bully what seems weak enough to quietly suffer under petty tyranny. We have a notable example of this in the boycott which the Typographical Society has proclaimed against The Dawn. The compositors have abandoned the old just grounds on which their union is established, viz: the linking together of workers for the protection of labour, they have confessed themselves by this act an association merely for the protection of the interests of its own members. The Dawn office gives whole or partial employment to about ten women, working either on this journal or in the printing business, and the fact that women are earning an honest living in a business hitherto monopolised by men, is the reason why the Typographical Association, and all the affiliated societies it can influence, have resolved to boycott The Dawn. They have not said to the women "we object to your working because women usually accept low wages and so injure the cause of labour everywhere", they simply object on selfish grounds to the competition of women at all. (Louisa Lawson, The Dawn, October 1889)

Henry Lawson may well be Sydney’s most famous poet. As such, he falls outside the aim of this project. On the other hand, his mother, Louisa Lawson, has been a lovely early discovery of my fossicks in the University of Sydney’s rare book digital collection. Louisa Lawson was not only a poet, but also a publisher, editor, activist, journalist, four-in-hand driver, philanthropist, republican and feminist. Apparently there is a block of housing commission flats in North Bondi named for her, as well as a park bench near the Botanical Gardens.

Lawson was born in 1848, one of twelve children, near Mudgee, rural NSW. She married a Norwegian sailor who’d jumped ship in Melbourne to try his luck in the goldfields. They settled in Eurunderee where he worked the fields or else scored building contracts, and she worked sewing, selling dairy produce and cattle. They had five children, though one died young. After a while they separated, and she moved to Sydney with the kids.

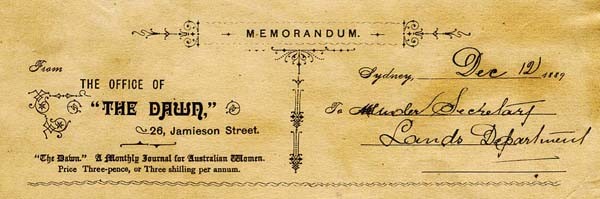

In Sydney, Lawson ran a boarding house to support the family. In 1887, she bought The Republican, a radical, pro-federation newspaper. She and Henry edited it for two issues, and in 1888 she founded The Dawn, the first Australian journal produced solely by women. The Dawn published feminist articles on women’s legal rights, education, labour and political representation. It also discussed divorce, domestic violence and mental illness, and offered household and health advice as well as featuring poetry, short stories and fashion tips. It was a commercial success and had national and international distribution. By 1889, Lawson employed ten women.

The New South Wales Typographical Association, a trade union that did not admit women as members, tried to encourage advertisers to boycott the Dawn. Lawson responded by publishing an editorial that directly addressed the hypocrisy of the union’s discrimination, and demanded support for women workers.

After her husband died, leaving some money, Lawson expanded her operation and began a press (which published Henry Lawson’s first poetry book in 1894). She also established the Dawn Club – a collective that met to discuss and campaign for policy reform. The Dawn Club and press offices became central to the campaigns run by the Womanhood Suffrage League of New South Wales, which formed in 1891. In 1902, (white) women were given the vote, one year after federation. Lawson then became active with the Women’s Progressive Association, working to get women elected to public office.

By 1905 the Dawn had ceased publishing, and Lawson retired, after publishing two volumes of verse (including The Lonely Crossing and Other Poems). She died in 1920.

Biographical remarks tend to dismiss Lawson’s poetry as the occasional expression of private matters, quite apart from the rest of her life. But her work is fascinating for what it reveals about her very particular, and utterly uncompromising politics. She was interested in a specific kind of progressive, Christian state that would enter the twentieth-century independent and with leading social reform. Her poems take nineteenth-century Anglo traditions, dislocate them from their habits of reference, syncopate them slightly with a lash of bush ballad jaunt and gut them of their interest in romantic love.

Of course, Lawson’s activism was specific to white women. Indigenous women (and men) were not allowed to vote in state or federal elections in Australia until 1962. Even then, it was not compulsory for Indigenous Australians to vote (as it was for all other citizens) and it was in fact illegal for a time to encourage Indigenous people to enrol as voters. As well, one of the first bills passed by the newly federated nation in 1901 was an immigration restriction policy, which initially explicitly prohibited non-European immigration, and later instituted ‘dictation’ tests for prospective immigrants. Post-war Australia saw various loosenings and amendments, but also many attempts to reinforce the policy in new circumstances. It was known long-term as the White Australia policy, and was not finally abolished until 1973.

In Lawson’s poetry, Indigenous subjects exist only as avatars, citations from classic stockman and drover narratives, labourers or seductresses, leading and losing men in unfathomable landscapes.

The white-mother-worker still dominates Australian ideology as subject and object of feminism. It’s interesting too to see how this particular representation endures so thoroughly in Australian poetry written by and about women.

--

'The City Bird'

A city bird once in a desperate rage

Threw over the bars of his screen

The whole of the seed that was put in his cage,

And it grew to a minature green.Sometimes when my troubles come up in mass,

And fate a new sorrow doth send,

I turn my wet eyes to that bright bit of grass

As I would to the face of a friend.For often it helps me to face a new day

Where Sydney at worst must be seen,

To look on the sparkling dew as it lay

On the blades of the city-yard green.Returning again at the end of the day

When I sit myself wearily down,

The scent of the grass takes me ever away

From the fret of a dust-covered town.I wish when they lay me away to rest,

And bosom and brain are serene,

Some friend would remember to plant o'er my breast

A tuft of that city-yard green.

Fossicks and offerings from Sydney