Inking outside the fox: type writing itself

'MITSUMI ELEC. CO. LTD.' by Eric Schmaltz & The Plastic Typewriter by Paul Dutton

Barney and Betty Rubble go to the Grand Canyon and send a postcard back to Fred and Wilma Flintstone. Fred and Wilma aren’t too impressed by the canyon but think the notion of a ‘postcard’ is a pretty neat idea. (I read this in a poem long ago. Unfortunately I can’t find the source. Send me a postcard if you know.)

*

Over the years, the typewriter has been important for visual poetry. For example, Dom Sylvester Houédard’s typestracts. Or Steve McCaffery’s monumental Carnival.

The typewriter frequently has assumed the role of both subject and predicate. The poem is what is typed, but is also the typing itself. And the typewriter.

Design. Designifier. Designified.

So: Paul Dutton’s The Plastic Typewriter (written in 1977)

So: Eric Schmaltz’s MITSUMI ELEC. CO. LTD.: keyboard poems (2013)

The typewriter remembers. It memos. Is dismembered.

The typewriter is a kind of recorder writing down the sound or the signs of the world around it – or maybe the boss’s dictation. Or records the words in the writer’s hands. A keyboard. Backwards braille: writing the fingertips.

Or the typewriter writes itself.

The materiality of ink. Of mark making. Each key or typebar broken free from the machine-determined grid. The typewriter presupposes fixed-width letters. The well-tempered typewriter. The standard-sized paper that is fed in an ordinary manner over the platen. This standard paper, considered as the destination for normative typewriting, isn’t blank. Instead it provides an invisible grid, its ‘open field’ like razed land waiting for a subdivision.

Ghost of the machine, rolling in ink. Typewriteromancy. The medium is the message.

Typewriter: participant in master dialogue. Capitalist scribe. Corporate memo monument-maker. To quote the Italian Futurist manifesto "Weights, Measures and Prices of Artistic Genius," by Bruno Corradini and Emilio Settimelli, from 1914: "A broken [typewriter] key is an attack of violent insanity."

The letters freestyling. Not bound by a rational Cartesian gri(n)d. If Kerouac pushed back conformist rationality through the road-long stream of consciousness by writing on the continuous scroll of an adding machine, here Dutton and Schmaltz also detourn typing by allowing the letters to literally break free. They remove them from the typewriter. Finger-signifier key separated from raised type letter. And indeed, they allow the typewriter to write more than just type. To write beyond letters. Impressions of the machine. Self-inkpression.

And the typewriter: a Flintstones era writing machine when looked at from the digital age. I’m writing this digitally, the text appearing on the digital representation of a page. There’s no ink. Only light. Pixel yourself on a boat on a river. But this newfangled thing is modeled on that old fashioned typewriting machine. Keys in QWERTY order. The scrolling page. The word processor defaults to modeling the typewriter experience. Digital mimicry.

So when Eric Schmaltz in 2013 deconstructs typewriting, it’s carbon ribbon dating. He’s a retronaut re(con)textualizing the typewriter and writing in both space and time. Indeed his typewriter is so changed by spacetime it's actually a computer keyboard. He quotes Kenny Goldsmith in the epigraph to MITSUMI: "The twenty-first century is invisible. We were promised jetpacks but ended up with handlebar moustaches. The surface of things is the wrong place to find the 21st century." (Goldsmith, "The New Aesthetic and The New Writing.")

And what of the infamous performance of Philip Corner's Fluxus piece "Piano Activities" (1962) where a piano was dismembered, each fragment sounding as it was severed from the whole?

The plastic typewriter? Plastic: not as in preformed prefab synthetic chemicals, but plastic: a lastic effort against the conforming confab of industry. Plastic as in the plastic arts. The plastich: a fluid line of verse. A verse made of fluids.

The prepared piano vs. the prepared typewriter.

But also: the unprepared typewriter not prepared for the word world it finds itself in. The ill-tempered, untempered temp writing on a typewriter, memos from beyond the desk where the quick brown fox can only jump over the lazy dog.

This is inking outside the fox.

*

Eric Schmaltz writes:

A close but not too close intergenerational reading of MITSUMI ELEC. CO. LTD.: keyboard poems by Eric Schmaltz & The Plastic Typewriter by Paul Dutton

A close reading for pieces like those in the MITSUMI ELEC. CO. LTD.: keyboard poems MS is difficult for me to imagine. When creating this series, I was partly informed by beaulieu’s notion of a concrete poetic. I, too, sought to create poetry that “momentarily rejects the idea of the readerly reward for close reading, the idea of the ‘hidden or buried object,’ [and that] interferes with signification & momentarily interrupts the capitalist structure of language” (beaulieu). The creation of this series was intuitive and instinctual rather than intelligent and intentional—more sporadic than systematic. Looking back now, it may have been a response to the more regimented work I was doing at the time, but also in dialogue with a generation of writers who, in part, incorporated this sort of spontaneity and play as part of their practice.

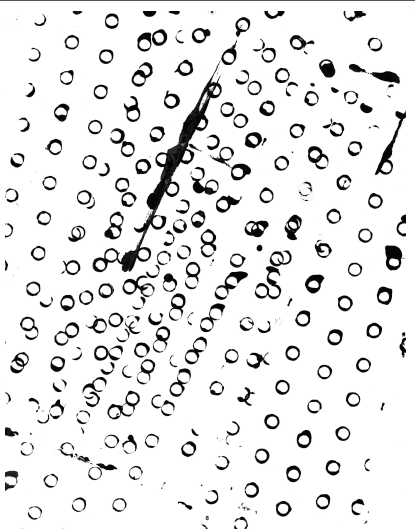

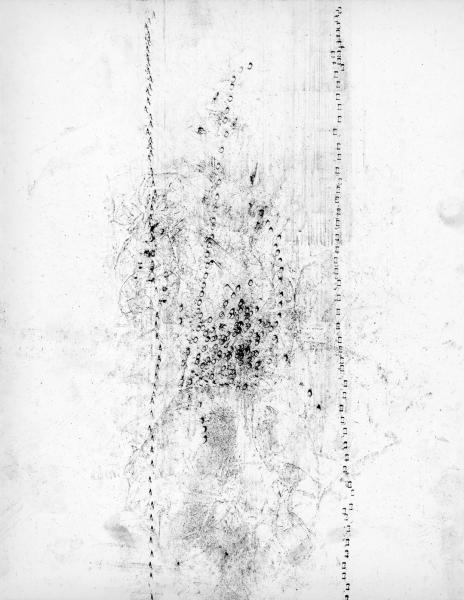

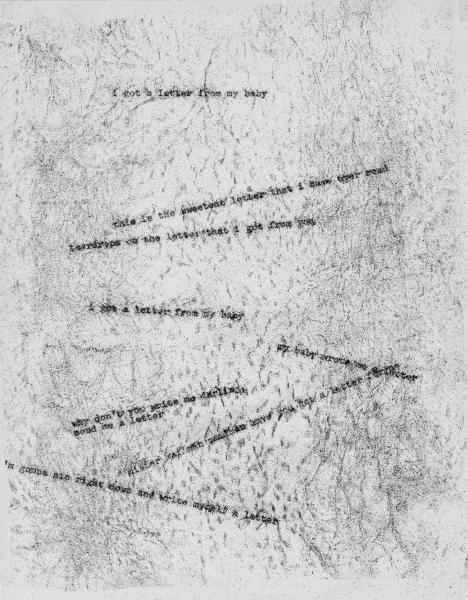

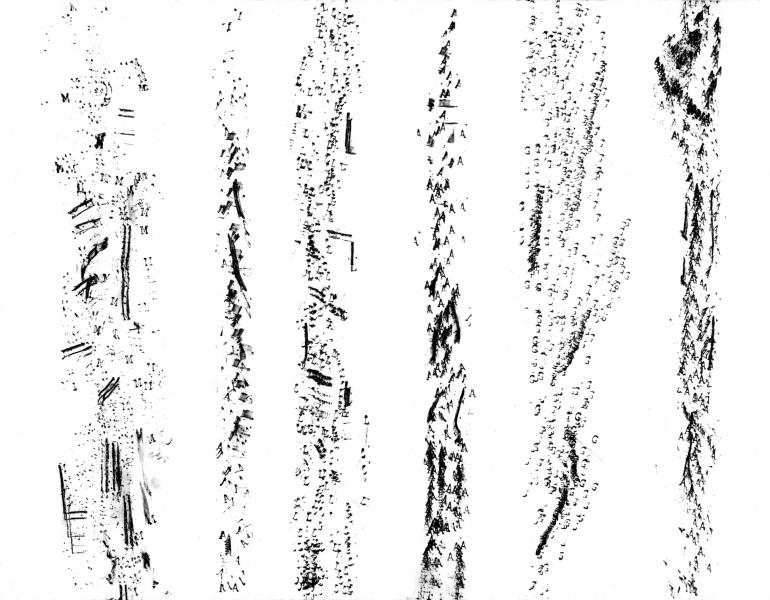

The Plastic Typewriter (1993) by Paul Dutton—one of the famed Four Horsemen and an outstanding practitioner of sound and concrete poetry in his own right—is a direct antecedent to my own project.[1] His suite of visual poems maps the materiality of the typewriter in a way that is atypical to its traditional use. To create The Plastic Typewriter, Dutton disassembles a typewriter and then uses its parts and carbon ribbon to create a series of visually stunning, dirty concrete poems. The language and its method of transmission become noise on the page, buried by the rubbings of carbon ribbons on bond paper and excessive overlay.

In this same vein, I disassembled a computer keyboard and since the device doesn’t have carbon ribbons, I used black paint (partially as a nod to Gysin’s oft-cited dictum), white card stock, and the keyboard’s pieces to seek out a similar effect. Like Dutton, I smear, rub, and imprint the page, defamiliarizing the keyboard and its function. While the poems stand on their own and in dialogue with each other, I find an exercise of intergenerational reading (Dutton from the age of the analog typewriter, and myself, born digital into the age of the internet) to be especially useful in fleshing out some of the concerns of my MS.

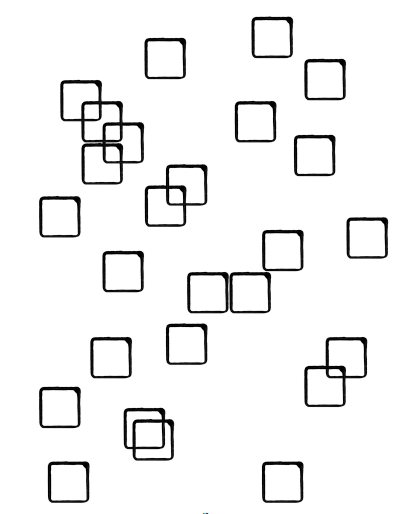

For example, one of the key differences between Mitsumi and The Plastic Typewriter is that Dutton incorporates language into his pieces using the typewriter itself. He involves language that resonate like lyrics from a blues tradition, “i got a letter from my baby/ this is the sweetest letter that i have ever seen” which suggests a sort of celebration or revelry in this deconstruction. In the case of Mitsumi, due to the nature of my device, the incorporation of language is much more complex, requiring several other devices—a scanner, a monitor, a console etc. thus implying a whole other series of systems. In an attempt to circumvent these complexities, I tried to imprint the keyboard pieces on the page (using individual keys like typeface on a typewriter), but only empty squares would appear on the page.

Comparing these physical gestures and their results gave rise to some interesting questions regarding our generational differences—what do these gestures, which I tend to read as emblems of our age, mean for our respective generation’s relationship to language and language devices? Does it imply or correlate to particular outlooks on language? Is this difference—my inability to directly incorporate language into the visual series—symptomatic of a virtual age? Is this material realization meaningful at all?

[1] It should be noted that Dutton’s text was actually created in 1977.

Thanks to Darren Wershler for his assistance with quoted sources. (GB)

Paul Dutton is a poet, essayist, novelist, and free-improvisational musician from Toronto, Ontario. Paul was a member of the seminal sound poetry group The Four Horsemen from 1970 to 1988, and since 1989 he's performed in the improvisational trio CCMC with John Oswald and Michael Snow. Paul has also worked with the vocal art supergroup Five Men Singing, among numerous other collaborations.Paul's 2000 album Mouth Pieces: Solo Soundsinging is available on PennSound, and his visual workThe Plastic Typewriter (1993) is on UbuWeb. You can find an online version of his 1991 poetry collection Aurealities at Coach House Books. Dutton's novel Several Women Dancing was published by The Mercury Press in 2002.

The Plastic Typewriter can be found here at Ubuweb.

Eric Schmaltz is a writer, reviewer, researcher, and former curator of the Grey Borders Reading Series. His creative work can be found in places such as The Rusty Toque, Poetry is Dead, filling station, The Incongruous Quarterly, dead g(end)er, and ditch, and recent literary articles have appeared in Rampike and Open Letter. Eric lives in Toronto where he will soon begin to pursue a PhD in English at York University.