Lyn Hejinian, 'constant change figures'

LISTEN TO THE SHOW

Above is Lyn Hejinian’s typescript of an untitled poem we’ve taken to calling “constant change figures.”

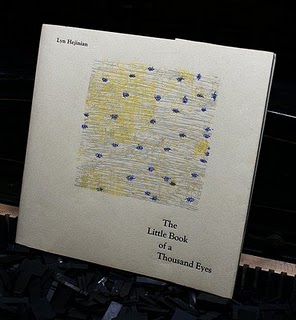

It is one poem in a series Hejinian has been writing, a project she currently calls The Book of a Thousand Eyes. If it is finished (perhaps, she tells us, in the summer of 2009?), it might consist of 1,000 poems; more likely of 310 or a few more of them (the number she had completed at the time this episode was recorded). Some poems in the series appeared in The Little Book of a Thousand Eyes, published by Smoke-Proof Press — although, please note, our poem, “constant change figures,” does not appear in that gathering. When Hejinian visited the Writers House a few years ago, she read 19 of these gorgeous little eyes, including ours. And it‘s the audio recording made during that reading that we use in our show.

It is one poem in a series Hejinian has been writing, a project she currently calls The Book of a Thousand Eyes. If it is finished (perhaps, she tells us, in the summer of 2009?), it might consist of 1,000 poems; more likely of 310 or a few more of them (the number she had completed at the time this episode was recorded). Some poems in the series appeared in The Little Book of a Thousand Eyes, published by Smoke-Proof Press — although, please note, our poem, “constant change figures,” does not appear in that gathering. When Hejinian visited the Writers House a few years ago, she read 19 of these gorgeous little eyes, including ours. And it‘s the audio recording made during that reading that we use in our show.

To what extent does our notion of nature’s picture — a picture of the many things we name “out there” — surprass the things we already know? We seem to deem memory nature’s picture. So to what extent is experience the result of our living in time, a state producing senses that are familiar and yet move us forward toward new and different effects?

So, truly, constant change figures the time we sense. “Figures” there — a transitive verb at that point — enacts things: change makes things, shapes them, renders them, gets things just so.

As you can tell from the recording, we were astonished that these words could accomplish all that thinking about words? Can you imagine writing a poem of nine triads, 27 lines in all, each line this carefully rendered — a poem that in all uses far fewer unique words than the total number of words in the poem, far fewer than conventional utterances would need to employ. Fewer, let’s say, than required by the language of philosophy telling of the same phenomena.

During our lively Hejinian PoemTalk, Tom Mandel in particular works out for us the way the shifting yet repeating triads are enacted. Bob Perelman focuses on Steinian memory (forgetting something himself along the way), Thomas Devaney on the power of turned-every-which-way phrasal variations, Al Filreis on the Steinian mode (again) and the poem as a possible critique of the ideology of experience.

March 9, 2009

Just begun to learn (PoemTalk #22)

Louis Zukosky, "Anew" 12

LISTEN TO THE SHOW

The Zukofsky recordings are remarkable! One of them was made in 1960 by Zukofsky at home, on a reel-to-reel tape machine. It was meant for the Library of Congress. It includes readings of some sections of the long poem Anew. PoemTalk 22 is a discussion of the gorgeous twelfth poem in the Anew series, which is untitled and gets mentioned by its first line, "It's hard to see but think of a sea." One gets a sense of its worked-at density from this first-line sentence alone.

The Anew poems were written between 1935 and 1944 and published in March 1946 at James Decker’s press in the small-format “Pocket Poetry” series. Marcella Booth has dated the writing of our poem precisely: January 16-17, 1944, a week before the poet’s 40th birthday. Several critics have contended that Anew was Zukofsky's attempt at a fresh start. William Carlos Williams, a great supporter of Z and an admirer of these poems, called the writing in this work "adult poetry." Perhaps he meant that Zukofsky was growing up, taking on seasoned topics. Certainly, at least, the end of our poem is quite personal, words coming from the poet's contemplation of his 40th birthday, of mortality's challenge to and provocation of open-ness. As Bob Perelman puts it (asked to compare this poem to others), "The poem is almost conversational. 'Gee, I'm 40. I'm thinking about my entire life.'" Much of our conversation--with PoemTalkers Perelman, Wystan Curnow (visiting us from New Zealand), and Charles Bernstein--is devoted to integrating the first part (full of the language of science) with the second (the personal retrospective).

Wystan, facing a vocabulary of science he didn't understand, wanted to look up the term "condenser" (what, after all, is a condenser really?), but then worried about his impulse to look it up. Is that a productive way of coming to understand Zukofsky's use in verse of electro-magnetism and wireless sound? "Condensed," after all, is an ordinary word--and a term of modernist poetry. (Bob points out Lorine Niedecker's contemporaneous use of condenser to refer to poetry itself, the act of writing in the modern way, in a famous poem that technically imagines the site of the poet-maker as a "condensery": "no layoff / from this / condensery.") "The poem," Charles says in praising its use of the referential language of science, "is not incomprehensible in that it will restore you to the knowledge you already had of what the word means."