Unsettled voices

Philip Levine’s passing last week brought renewed attention to Detroit poetry in the national press. Much of that coverage has focused on Levine’s origins in Detroit and his attention to the working class. For example, Margalit Fox, writing for the New York Times, describes his work as “vibrantly, angrily and often painfully alive with the sound, smell, and sinew of heavy manual labor.” Fox echoes the Norton Anthology of Modern and Contemporary Poetry, where the biographical note on Levine begins with these lines: “Working in the auto plants of Detroit in the 1950s, Philip Levine resolved 'to find a voice for the voiceless’ — the unsung factory workers of America, blue-collar laborers on assembly lines.” Voice, like sound and smell, becomes a sign here of working class representation, and, presumably, something “authentically” Detroit.

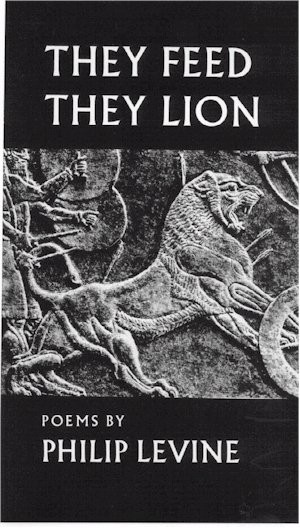

My first sustained engagement with Levine came last fall, when I included him in my course on modern and contemporary poetry precisely because he was a “Detroit poet” (and included in the Norton, from which I was teaching). The narrative poems of place were less compelling to me than “They Feed They Lion,” one of his best known poems, written in response to the race riot of 1967. This text is complicated and troubling precisely because it challenges the idea that one can locate a single voice capable of representing the voiceless. The text's white speaker mimes a black vernacular to describe a “growing lion” of anger, alienation, and violence. Here is the final stanza:

From my five arms and all my hands,

From all my white sins forgiven, they feed,

From my car passing under the stars,

They Lion, from my chldren inherit,

From the oak turned to a wall, they Lion,

From they sack and they belly opened

And all that was hidden burning on the oil-stained earth

They feed they Lion and he comes.

When I first read this stanza, I reacted to its easy evocation of violence and retribution. Who has the right to declare their own forgiveness? Or who can describe the origins of someone else’s anger with such precision? But further reflection led me to believe that the adoption or mimicking of a voice that is not the speaker's own destablizes and undermines any simple authority or authenticity that would make it a “voice for the voiceless.” The play of the voice deliberately hollows out the poem's claims, leaving the speaker’s articulation self-consciously incomplete and unwarranted.

In an interview from 1999, Levine suggests that this play of voices, where authenticity is born from imitation, can be traced back to the poem's origin. The title comes from an exchange Levine had with a black co-worker named Eugene, who “laughed...because he knew that he was speaking an English that [Levine] didn't speak, but...would understand.” Levine claims that Eugene was “almost parodying” himself, inhabiting his language as a peformance that still marks a difference. If Levine is a poet who gives a voice to Detroit, that voice carries with it moments of difference, like “They Feed They Lion,” when articulations collide, morph, and transform themselves.

Detroit poetries: Field notes