'So Translating'

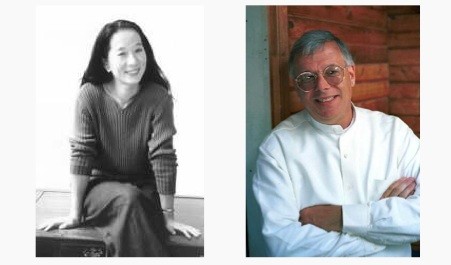

Zhang Er and Bill Ransom in conversation

Zhang Er’s book So Translating Rivers and Cities was published by Zephyr Press in 2007, the original Chinese poems and the English translations en face. We spoke about the book for CCP episode 161 in 2008 (listen there for her reading in Chinese of the poem). Novelist and poet Bill Ransom was one of the co-translators, and he joined us for the drama in studio that day. (Other co-translators who contributed to the book are Bob Holman, Arpine Grenier, Timothy Liu, Susan Schultz, and myself.) The transcription was done by Claire Sammons, now a graduate student at Columbia College in Chicago.

Leonard Schwartz: Today’s guests in studio are Zhang Er and Bill Ransom. Zhang Er has a new book out, entitled So Translating Rivers and Cities. The poems are translated from the Chinese by a number of people, including Bill Ransom, poet, author of six novels and six collections of poet. Both are in studio. Welcome Zhang-Er.

Zhang Er: Thank you, Leonard.

Schwartz: And welcome, Bill Ransom.

Bill Ransom: Yes, thanks Leonard.

Schwartz: Great to have you both here and thinking on your feet, literally in the studio. Zhang Er, So Translating Rivers and Cities brings together a number of different periods of your writing, and a number of different books, as I mentioned published by Zephyr Press. I was hoping that you and Bill could read the extended poem, “Mother Event” from the book. Can you say a little about the poem, Zhang Er, and Bill could you say a little about the translation process?

Er: Well “Mother Event” is literally a mother event. I wrote this poem after I gave birth to my daughter, Cleo. Her Chinese name is Yu Ran, which is how this poem is dedicated. Basically I am struggling after giving birth through this phenomenon of post-partum depression. I didn't know it at that time, but for a whole year long I was writing a single poem and raising up a daughter and doing all the motherly things, breast-feeding, changing diapers and so on and so forth. So during that busy year I composed this poem. I was thinking about a book-length poem but that didn't work out so after the year passed I kept going back to the poem and every time I looked at it I trimmed off part of it. More or less this is the result. This is a whole year's work under all kinds of physical and psychological change. So what you're going to hear is a highly edited version of what I had been going through for that year.

Schwartz: “Mother Event” is one of the longer poems in So Translating Rivers and Cities. Bill Ransom, I'm wondering if you could say something about translating collaboratively from Mandarin Chinese with Zhang Er?

Ransom: Well, it was a great experience, a learning experience for me. It was the toughest poem that we worked on for me because it's the most female. So that led to a lot more delicacy on my part to try to be attentive to the translation in the sense of respecting the gender more than I might if it were a male. For me it was a fun stretch even though it was tough. And working with Zhang Er —

Schwartz: Are there any stretch marks to show for that stretch?

Ransom: Well, perhaps in my psyche. We sometimes spent hours over a word, and I learned to re-respect words where I had begun to take them for granted. For me it was fun on many levels and a challenge that I felt we met well.

Schwartz: The results are remarkable. One of the things about “Mother Event” and the reason I ask you to read it, Zhang Er, is the way it is so sound based in the Chinese; the way in which language in its inception (at least the way most of us learn it) is oral. It’s something the mother says to us or an elder says to us and the poem has those dimensions alive in it even as it is an act of writing.

Er: I want to respond to what you just said, Leonard. This poem was composed after the first year after my daughter’s birth; the child is really prelingual at that point. The most challenging part in composing this poem is that I was struggling to get these new prelingual feelings and physicalities and relationship into words. As a poet, I think this was one of the most difficult things I’ve ever done. I don’t know whether the result would be something appreciable, but the process for me is still very memorable.

Schwartz: I think the poem is remarkable in its ability to explore a certain prelinguistic state. I must also add as that same child's father I remember very well the pre-lingual state you were in yourself at that point, which consisted mostly of grumbles, groans, frying pans over my head, and so on, though it was all worth it. Well I don't know if it’s all worth it, but it’s partially worth it, thanks to the poem and the kid. Maybe I should shut up.

Er: Well, Leonard, talking about frying pans, I wonder if you can ever pick that up from this poem. Because he (Leonard) figures so little in the poem that as the father I think he has to put the frying pan in there to get some sound effect for himself.

Schwartz: Um... To the poem?

Er:

Mother now

dizzying sensation of sitting on high—

so small, so soft

flesh

a bite in the mouth

a belly of water

*

to begin

they peel out the sterile plastic pipette

from its paper wrapper

in a single motion—

(like stripping chicken from its skin)

no wasted movement

float

roof, pillar, sheep and cows

sink from the waterbed

natural

not yet flooded with

spirit or mood

they repeatedly change the paper pads

rewrite the sky-blue

the language of perfection:

separate out this distinct contour you

slippery in a sheet of cream

freshly minted nailtips:

one, two, three, four, five

light panorama

all blue:

sofa, gowns, gloves, mattress pad, blankets, tiny terry-cloth hat

sets off

a bit of flesh

(blue)

eyes (blue)

*

who let them

take you away—

Draw blood

Tap spine

Stick electrodes to chest

Seal into the glass incubator

Bloody stains on tiny feet!

Hold it up

against the skin

(a clutter of tubes, wires, monitors)

suck eyes of the breasts throbbing tight

refuse the fake

loud cry

violent shake

(it can cough, too!)—

return me my flesh!

*

he says—

“I saw the hair first, black hair”

“blood”

blood?

“screams” and “cries”

Cries? Screams?

*

let’s go home

OK

leave this place full of hands

too bright too noisy

whether rain or heat

we have a window, with shades

bassinette blankets turn off the light

*

it can cry without tears

(like a bomb already set, but with an erratic timer)

hungry cry

wet cry

tired cry

sleepy cry

delighted

(when lacking means of expression it doesn’t smile)

dressing cry

full diaper cry cry cry

belly down cry

held upagainst the chest

up and down cry

*

when not crying

it (can)look at me

those eyelids

Open the door

let “me” in

eye of eyes

clarity of no distance hide me

is me! (is this mine!)

put this mirror down—can’t

little hands little feet a little bonnie

tight fists

stinky

won’t open up

it rains

hualahuala water

a little spider

slides down the hill

*

these faces

dark, wrinkled, fat and thick, powder soiled

once held to breasts, kissed and kissed again?

This perfection of mother’s bosom

would stand in lines

to join these faces

on the bus?

don’t let them watch

watch you breaths shallow, light pink, eternal

cheeks of water

wild lilies spread from chest to

chubby legs’

little

fork.

Because you are not the same.

Not the same clean

not the same perception.

*

these you

these I

one, two, three, four, five

six, seven

all pretty orchids

go to heaven

*

The expression of no “I”

how can that be called an expression

is the loveliest expression

is the only possible expression

*

in the past did I, too, enjoy

this endless

hold, pat, embrace, carry, rock, hug, piggyback

clean, wash, rub, brush, comb, stroke, kiss, smooch

smile, breastfeed, sing—

always a good mood no temper

always keep up even when tired, sleepy, exhausted, bored and can’t stand one

second more?

Don’t recall drinking your milk

“‘til you’re a year and a half”

don’t remember eating my doody

“all over your face”

remember the accidents at night

“don’t remember your teething history”

fat belly, small eyes, thick voice, big girl

(do you remember now?)

so later on it grew into beauty itself—

oval face, willowy waist, long legs, delicate ankles

these victories forgotten

allow us

to grow up without turning back

temperamental and with no patience?

Achievements left you

are not you

only suspicions—

you did hold me tight

(even if I don’t remember and cried my best)

you held me in good spirits

didn’t toss me into the river

mom

these crystallized

tears

and

all

that love!

Has nothing to do with your personal story

the manifestation of life reduces to purity—

all there is worth measuring is

body weight

why you only like blue

how many oz. of mashed fruit you ate today?

*

one two three four five

climb the slope where the tigers live (of course not to hunt, PC)

don’t see tiger slinking around

so plant this watermelon (Hey, Hey)

melon grows no melon seeds

becomes a turtle in the reeds (Hey, Hey)!

Hmmmm, BaoBao

sleep

sleep

BaoBao

lack of any rhythm

is it the rhythm?

Salty sweet bitter spice

become superfluous:

double-fold eyelids sticky with

rice flakes and mashed peas

draw mom’s tongue:

squeaks Hey, Hey

don’t scratch your eyes

*

this love

tears

and

a bundle

that can’t

be

separated!

Hands that hold you tight

throw you down the river

now

or later

you assume

she will recognize you?

on the road?

Girls

born

die

born again…

why not

eternally

the daughter?

You

what right do you have to rob me

one hour

of every three?

Cry

you still cry

why can’t I?

*

(the weight of this curve on my shoulder

soft)

your forehead

shines

compare it to what?

A leopard cub

prickly claws

two bloody scratches…

*

days not needing sugar

are not bitter

days of milk

white and pink

a chin dripping drool

no one can compare to you

embrace you embrace self

newborn: pooched belly, crossed legs, tender thoughts, impossible feeling

Dig a big hole

bury you my body

and

this memory: the story of mother and child

flesh-and-blood their positions and personal pronouns

surprising water rises

all drown

drown

because it is not possible

Schwartz: About the book as a whole and I think it applies to this poem in particular, Donald Revell wrote, “In So Translating Rivers and Cities Zhang Er offers a glorious scroll or map of transformations. Everywhere in these poems the image of enchantment becomes luminous fact of enlightenment. Wisdom precedes through the enchanted eye into pure mind finding no obstacle, broaching no impediment. The effect is of a sudden, entirely true transparency.”

Bill Ransom, Zhang Er, I guess I would just ask you just one more question about the translation processes if I might about “Mother Event.” I agree with what Donald Revell says in that comment, “the effect is of a sudden, entirely true transparency” but I'm sure that in the trenches, so to speak, between the two languages figuring out how to get from Chinese to English it felt anything but transparent. Could you say a little bit about the process you went through in making over "Mother Event" from Mandarin Chinese into an English text?

Er: I think Bill has to answer the question because I wrote the poem and for me every thing's crystal clear.

Ransom: I’d like to say that every thing was crystal clear for me too but it didn't work that way, it took quite a bit of conversation and that was very enjoyable conversation I might say. Not necessarily translating word for word because I think that that would not do justice to the culture of the poem. So one of the challenges was to render something into English that in this culture would pass for that poem in Chinese culture. That was probably the biggest challenge.

Er: I particularly remember the two nursery rhymes in Chinese which are also an interest of mine right now, trying to do a nursery rhyme collection. Which is very much a colloquial counter phenomenon. Every generation, every single mother modifies them, is making up different rhymes just to have something rhythmic in the process of nursing or childcare. So I made up half kidding, half from memory in this poem and some of the images can't really be directly translated to recreate the sense of nursery rhymes because America obviously has its own tradition of what type of nursery rhyme is used currently. You even discuss God's presence in one of your rhymes!

Ransom: Well, I won that one. As I remember the conversation the nursery rhyme that I chose was actually from a Beatles song “One two three four five six seven, all good children go to heaven,” to match the rhythm of something that Zhang Er had. Her response was “Bill, in China we don't have heaven.” But changing the children to orchids and then keeping the heaven was I thought a wonderful compromise.

Er: And the original is also a kind of flower. I don’t know exactly the English translation of that word; it’s a plant so I think the transformation is good. I wanted to record it isn't a rhyme that existing rather than to create that kind of a balance from the poem between the mother and the child and all of a sudden you have this outside song anchored there.

Schwartz: Zhang Er, the book is of course your poems but you worked with a number of different translators; Bob Holman, Arpine Grenier, Timothy Xu, myself, Susan Schultz, and Bill Ransom. Could you say a little bit about the whole process and what was distinctive or distinctively difficult about working with Bill Ransom, since we've got him right here?

Er: Well being a college professor, Leonard always wants me to rank things. I think for this particular conversation I will say that Bill Ransom is the best translator! It’s a pleasure to work with all different poets, everyone has a different style. Because all these translators are quite established in their own work, they are clearly going to bring their style into the translation which for me is really a welcome thing to have happen because I do want to have the translated work as a poem in English rather than just a draft from the Chinese translation. Bill and I are working with a group of poems that has a plot to it, more narrative than some of the other work. I think Bill’s being a novelist and storywriter and his own poetry being anchored in events works best here compared to my other work. I think the style matches very well.

Schwartz: Zhang Er, this has been great. Bill Ransom, great also. The book is So Translating Rivers and Cities is published by Zephyr Press. Anyone who wants more info on Zephyr Press or this book could go to their website, www.zephyrpress.org.

Cross Cultural Poetics commentary