Marvin K. White: 'our name be witness' // 2011

Your moving ahead is not leaving someone else behind

When I think of Marvin’s writing, I first think always of such an abundance of food: the kind of rich, filling nourishment that’s associated with Black southern foodways. Opening his third book at random yields okra and carrot cake and corn and peanuts and the hot sauce jar all in one poem, but adjacent pages offer teacakes and fried chicken and sorghum syrup. It’s the kind of food I learned to love when I began a fellowship at Taylor Memorial United Methodist Church, which was founded in the course of the Great Migration of African Americans from the southeast to California, and still stewarded by ministers and congregants with roots in Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Which is funny because I’m pretty sure Marvin and I only ever sat down to one real meal together, at (as I recall) a Mexican restaurant in east Oakland on one of our first friend dates. I don’t even remember what I ate. The food fellowship that sticks more in my mind was coffee and pastries at Sweet Bar on Broadway, where we’d get together when our schedules permitted. Of course, we always used to bump into one another at the Goodwill by Oscar Grant Plaza. I never knew anyone like Marvin for a Goodwill.

We met first through Rev. Lynice Pinkard, who lugged in volumes of Gramsci and Weber to sell at Moe’s Books when I was working the buy counter one day. (This would have been 2010 or ’11.) I asked her what she’d done her doctoral work in, and she said that these books were actually what she’d studied for a Masters of Divinity at the Pacific School of Religion. Thus began my years-long conversation with the Black, queer, anticapitalist pastor who would become my first Christian mentor and teacher. She introduced me to wonderful preachers and theologians, including Rev. Donna Allen and, some years later, Marvin K. White.

I heard tidings of Marvin before we ever met. His mashup of poetry, preaching, and queer gnosis were already starting to be legendary before I ever saw him do his thing. He was a friend to the community at First Congregational Church of Oakland, where he tore the roof off with a sermon on “the Q source” — riffing on the ur-text of the Gospels which German scholars refer to as Quelle, or Q for short, as well as the queer source rooted in barstool knowledge and dance clubs bouncing to Frankie Knuckles. Afterwards we went to the Whole Foods across the street for a coffee and ran into Brontez Purnell (typical Oakland story). Brontez asked Marvin what he was up to, and Marvin pointed to the church marquee, which read: “Are You There God? It’s Me, Marvin.” Brontez said: “Good luck with that.”

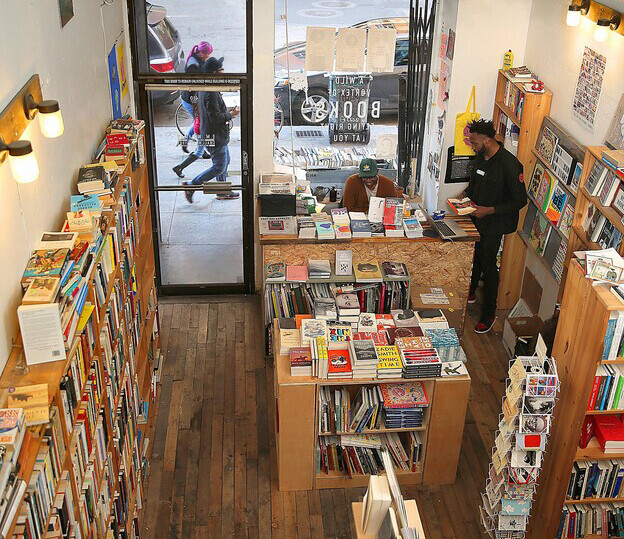

Somewhere along the line, Marvin and I decided to do a reading together, and in planning it out we struck upon the notion to frame it as a religious service, with an order of worship including elements like the passing of the peace and joys and concerns of the people. Jacob Kahn, at the now-defunct Wolfman Books on 13th Street, around the corner from where I worked between 2016 and 2019, was kind enough to host a reading. (The photo above is an interior shot of the bookstore, with Ryanaustin Dennis and Christian Johnson at the front of the shop.) I came prepared with a portable Numark turntable on which I played the same battered Staple Singers album I put on before every meeting of the Agape Fellowship, the house church I copastored with Sarah Pritchard on Alcatraz Avenue. I’d gotten the disk out of a box of free records at the Omni. I’m pretty sure we prepared a sort of church bulletin to hand out, but I don’t have a copy anymore.

The strands Marvin weaves together in his performance, preaching, and curation (as in “White Noise/Black Masks,” the group reading he put together at the Berkeley Art Museum for the Black Life series I curated with Chika Okoye) also run beautifully through his published work, which often operates in the logic of the DJ’s crossfade — a technique he once discussed from the pulpit. It’s when you move the bar from one turntable’s output to another’s, but slowly enough that for a moment both tracks are audible.

You hear the crossfade and blur in Our Name Be Witness — beginning with the the ambiguity of the title. What is that be doing? In English, be can function as what’s called a hortatory subjunctive, and the title could be supplied with a missing verb: (Let) Our Name Be Witness. Or it could be the indicative be of the book’s colloquial African American English, as in Jeff Chang’s book entitled Who We Be. Of course, it could be both. It’s probably both.

After the first, short poem, “Devil’s Food” (see?), which is the only enjambed text in the book, we enter a space of monologue whose source is uncertain. The prose poems that comprise the book are of varying length — some pages long, some only a few sentences — and they cover many different subjects. Proceeding through the book, themes begin to reoccur. The speaker, or speakers, are frequently addressing a second-person “you,” often with advice or encouragement. “Sometimes you gotta have a different measure than a day.” “You got a gift for teaching children.” “You in the thought of God.” The blur is not only in the speaker, who mostly seems feminine but could be a mother, grandmother, older sister, or auntie. It is in time — are we in an epoch of the ancestors or in the immediate present or both at once? It is in space — are we in the south or in the west? “A river remind you Louisiana and Africa and Oakland cry the same.” Late in the book, we realize that this text is, in part, a work of mourning. And so we are also in the crossfade where those we love are simultaneously vanished and present, and we have to figure out what that means. “There is always something missing. I put it down and I can never go back to it.”

Marvin is often on Facebook, so I messaged him to ask whose photograph was on the cover of Our Name Be Witness. He replied: “my great, great grandmother, Nora Lee aka Galley Mama.” She is one of the dedicatees of the book, which is “for the women I come from and through and who come through and for me.” She’s among the begats in the first prose poem. She is remembered. As it says in the book, “My name be witness. My name finally be my name.”

A Holy Forest