How I got here, and where we're going

Or, welcome to Jacket2

It feels very fitting to write this opening note on April 5th, the fourteenth anniversary of Allen Ginsberg’s death. Certainly Ginsberg spent the majority of his life as an ardent and innovative advocate for the cause of poetry, in a manner not dissimilar from that of John Tranter, whose Jacket Magazine (born within six months of the poet’s passing) we now carry on into the future as Jacket2. However, Ginsberg has a more personal significance for me because I can honestly say that without having encountered his work around the age of fourteen or fifteen I wouldn’t be here today working at Jacket2 and PennSound, as a poet and a scholar, as a socially and politically-conscious human being. Instead, I’d likely be a doctor or a music journalist or something far more lucrative and life-affirming than this strange life I’ve stumbled into; most days, however, I’m very happy with the choice I’ve made.

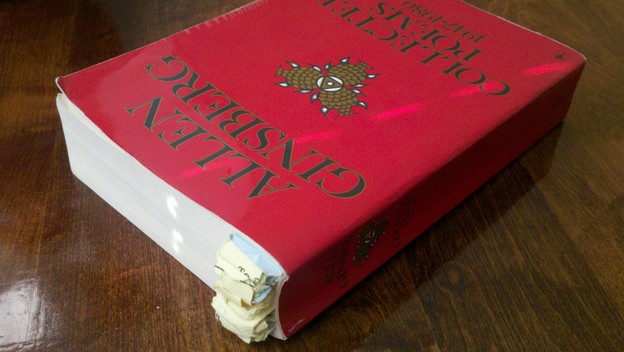

The strange thing though is that I really have no idea how I came across Ginsberg’s work in the first place. I know that my mother dutifully trudged out to a Waldenbooks in a mall somewhere in the Philly suburbs to buy a copy of his Collected Poems 1947-1980 (pictured above) as a Christmas present, and I’d guess that I’d requested it after coming across a story on the poet in Spin or Rolling Stone (both of which I read faithfully at the time). What I do know for certain is that I devoured the collection with tremendous fervor, loving not only the clear-cut classics like “Howl,” “America,” “A Supermarket in California” and “Sunflower Sutra,” but also the offbeat pieces that showed me things I’d never realized poetry could do before: the intense collage-work of “Wichita Vortex Sutra,” the rabid chant of “Hum Bom,” the novel constructions behind poems like “I Am a Victim of Telephone,” “Grafitti 12th Cubicle Men’s Room Syracuse Airport” and “Junk Mail.” As you can tell by the photo above, the spine bowed mercilessly by dozens of bookmarks (the yellow ones torn from a comment card for the local theme restaurant, Nifty Fifty’s, the blue ones scraps from a college bluebook cover), I had a lot of favorites.

Reading Ginsberg soon led me to discover other Beat authors like Gregory Corso, Lew Welch and Philip Whalen, along with affiliated poets like Robert Creeley, Frank O’Hara and Anne Waldman (and I still don’t really understand why the last two are featured in Penguin’s Portable Beat Reader). More important than the lateral readings, however, were the backward glances through the canon, leading me to William Carlos Williams, to Walt Whitman, to Rimbaud and Blake. As a teenager I didn’t have older siblings to introduce me to a world of culture, I didn’t have particularly sensitive or encouraging teachers and I didn’t have literary-minded friends, but I’d found this work that appealed to me in a way that the dusty relics I was offered in my high school English classes never would, and suddenly I felt a connection to a literary tradition larger than myself. What I didn’t realize until after Ginsberg had died was that this tradition was a contemporary one as well — that this author I knew and loved so well was (up until that point) living in the same world I was and responding to it — and that it would continue into the future, where the Beats would take a less prominent, yet still important role in my overall field of influence.

Of course, there’s nothing particularly new about this story: entire generations (including many of you reading this) have had similar experiences. I’ve somehow lucked into teaching a freshman seminar on the Beats once or twice a year, and one of the purest pedagogical pleasures each term, without fail, is seeing so many bright students fall under the same swoon that I once did and then start asking for extracurricular reading suggestions. This is how our anti-canonical canon is promulgated — by word of mouth, by tracing lines of influence and social coterie, by seeking the work that might not be readily available in your surroundings, or approved by your teachers, but is nonetheless out there waiting for you to find it.

Moreover, the ever-growing role of technology and media in this process — as auratic relic, as cross-reference, as gateway drug — cannot be understated. As a teenager, I’d taped a brief Ginsberg set from the Geraldine R. Dodge Poetry Festival that had aired on the local PBS affiliate, along one of MTV’s “Buzz Bin” airings of his video for “The Ballad of the Skeletons” and watched both incessantly. I mourned him in an America Online “Beat Generation” chat room (founded by the wonderful Diane DeRooy — where are you now, Diane?) with the incredibly embarrassing screen name “Beatnik517.” Eventually, in college, I saved up for the CD box set, Holy Soul Jelly Roll: Poems & Songs (probably $50-60 at a suburban Borders), and must have listened to those recordings hundreds if not thousands of times. Money was unfortunately an obstacle for me then, but within the sort of poetic gift economy that John Tranter envisions in his iconic essay “The Left Hand of Capitalism,” those boundaries are eliminated. If resources like PennSound and Jacket had been around at the time, I’d have had an unbelievable wealth of materials — thousands of recordings, tens of thousands of pages of essays, interviews, reviews and poetry — at my disposal, and all for free.

This is precisely why I happily keep the memory of my formative experience with Ginsberg’s work in mind as we launch Jacket2: as a reminder not only of the redemptive power of poetry, but also the democratizing power of free access to culture. Certainly, we’ll do our very best to uphold the high standards that John Tranter set for Jacket — no small task, indeed — and we hope that faithful readers will not only be pleased with how we live up to past example, but also excited for the new directions in which we’ll be taking the journal.

Editor, Jacket2 and PennSound