The family circuits

Uninterrupted tissue and interspecies continuum

Bio-poetics is an art form not interested in some Modernist purification of the tribal dialect but instead in a creative mongrelization of the planetary genome. In Grammatical Man, Jeremy Campbell refers to “basic resemblances between genes and language that are beyond dispute” — also beyond dispute are the resemblances between living organisms at the level of their molecular components. David Kremers asserts that “nature’s factories are smaller in size than what they produce” because each unit measure of living material, from organ to tissue to cell to molecule, is itself a manufacturing plant working from common goods.

A virus’s skill at self-manufacturing lies in its power of mimicry, its adeptness at impersonating its host cell’s local dialect. Such impersonation is possible because of a shared chemistry across the living kingdoms. When traced outward in any direction, a human gene’s family tree quite rapidly finds branches deriving from non-human sources. Our orating, word-issuing jaws were once gill slits, our pen-wielding hands were once fins, and so Natasha Vita-More’s Primo Posthuman project foresees the divergent attributes of our fellow species (including sonar and infrared vision) re-implanted into the human apparatus. The collage of Modernist verse can now be applied to the human form itself, in a bricolage of traits and behavioral plug-ins.

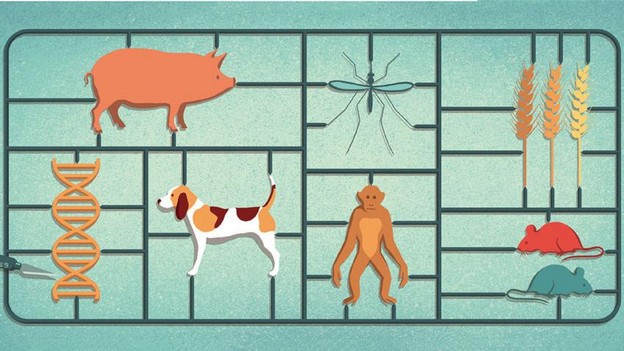

This sort of engineering will continue to press on the barriers between species. The too-tidy containers of the classically Latinate binomial nomenclatures for plants and animals are being taxed and tested as we crossbreed from every angle. Bacteria form the fast lane of evolutionary travel, speeding along at a rate of innumerable mutations per minute, and so bio-art hops a ride on a microbe’s express-track malleability. Our genome is a score whose compositions offers options for arrangement and setting, and so-called “junk DNA” may hold one of the keys to further genetic adjustment.

Poetic language has long accentuated analogic and metaphoric connections, rooted in part in Ficino’s vision of nature’s “uninterrupted tissue.” Bio-poetics underscores this continuum but also confronts certain ruptures and breakages, reading the gaps between species as artistic challenges. Matt Ridley’s book Genome imagines a genetic word petitioning a “porridgy” ocean of prebiotic elements and forming the initial phrases of life and eventually resulting in the “porridgy contraption” of the human brain. This porridge can now be stirred in new ways, with atomic replicators creating objects on demand, bypassing organic procedures and “writing” at the level of the atom.

Just as Ovid, at one of Western verse’s several cornerstones, reveled in interspecies transformations of humans into riverside laurel trees and wind-borne echoes and bullheaded maze guardians, bio-art also leaps across species hurdles. In Walden’s“Spring” chapter, looking at the motes and clumps of a half-frozen sandbank thawing into a variety of organic shapes resembling leaves and livers and lungs, Thoreau predicted that a sufficient level of heat would cause human beings to evolve into new and extended post-human forms. Today, this heat is supplied by Bunsen flames and laboratory radiation and substances boiled beyond their temperature of saturation, allowing silicon and carbon (and the virtual and the vegetal) to intermarry.

The poet-as-shaman assisted in consolidating individuals into a tribal group, and now the bio-poet reminds individuals that they are assembled congresses of sub-beings and microbial interactions. These interactions are open to all sorts of variety because a cell is an active interpreter and not a passive translator of a gene’s “commands,” which are actually chemical “suggestions” according to B. G. Goodson. Atomically, our “information” is “in formation,” but increasingly willing to break from its rank and file. This flexibility at the level of component behavior increases the palette of bio-poetics.

Walt Whitman in “This Compost” is aware of his own bodily components eventually being re-subsumed into the nutrient pool, and many bio-artists are similarly cognizant of their status as ex-detritus and detritus-to-be. In Goethe’s claim, “Every animal is an end in itself,” but a bio-poetically engineered animal is also a brief pause awaiting its recycling as the epochal, gradual process of genetic “drift” is accelerated into a more abrupt genetic “dart.” Writing inside of an organic molecule means using animal substance as a medium. Ancient writing on vellum, or treated animal skin, has by now evolved into writing on an animal’s innermost, still-living tissues.

Classically pastoral verse, which depicted a solitary figure “tending” to a grazing flock, is now supplemented by a material poetics intent on “bending” said flock into a new bestiary, where the diploid pairing-off of creatures on Noah’s ark is a more polyploid riot. The classical “ode to” a fallen or sacrificed hero is now an admission of what is “owed to” other life forms in a bio-art well aware that the word “mongrel” derives from “among.”

A p.s. to Genesis: notes on transgenic/bio-poetic art