El Corno Emplumado / The Plumed Horn

A voice of nonconformity

Within The Little Magazine in America Collection at DU Libraries is a complete run of Sergio Mondragón and Margaret Randall’s El Corno Emplumado / The Plumed Horn, edited in Mexico City from January 1962 through July 1969. A primarily bilingual quarterly, the magazine published thirty-one issues that include work from writers and artists across the world, though many were located in Latin and North America at the time of publication. It so happens that a full run of El Corno Emplumado is digitized and available for perusal online at Northwestern University’s Open Door Archive, and if you click through for a visit, you’ll quickly gain a sense of who and how many, and the magazine’s look and substance.

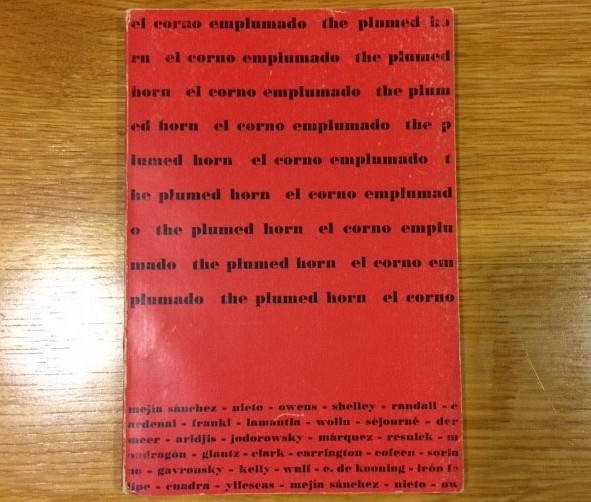

In short order El Corno Emplumado became recognizable. Of Issue 3 (take a look at the notes Randall’s made about each issue of the magazine) Randall writes, “The typographical covers, with the publication’s name in continuous script across the top and the issue’s contributor’s [sic] names in continuous script along the bottom, each in its own bright color, began to be familiar to readers far and wide.”

After supporting Movimiento Estudiantil (the Mexican Movement of 1968), El Corno Emplumado was forced to shutter. Randall spoke of this period in a 2015 talk at The University of Mexico’s Tlatelolco Cultural Center:

1968 was a watershed year in Mexico. Students, ultimately joined by workers and farmers, staged giant protests against governmental overreach and wrongdoing. The vast majority of the country’s intellectuals and artists sided with the students. Similar upheavals took place that year in the United States and France. But Mexico City was about to host the Olympic games, and the Diaz Ordáz administration was fearful of losing its huge investments. It unleashed a deadly crackdown ten days before the games opened. Along with this violent repression, it withdrew patronage for progressive ventures, and most of the small literary magazines had to shut down. El Corno Emplumado gave its unequivocal support to the movement. It was finally forced to cease publication when I went underground in 1969.

In seven-plus years of El Corno Emplumado’s existence, the magazine was “a voice of nonconformity, of resistance to a stultifying status quo, a loud answer to those who told us poems could only be written about subjects approved of by whatever academy was in vogue.” Sounds familiar, no? The magazine leaves us a fantastic map of — to borrow a phrase from Randall — the world of letters of its time.

The issues of El Corno Emplumado that most hold my attention include poems by besmilr brigham (No. 19, July 1966) and Alejandra Pizarnik (No. 13, January 1965; No. 17, January 1966). When Pizarnik was first published in El Corno Emplumado, she had recently published her fifth collection of poetry, Los trabajos y las noches (1965), at the age of twenty-nine, and returned home to Buenos Aires from Paris. In the aforementioned issues, six of Pizarnik’s short, lyric poems (No. 13) and two poems lineated in prose (No. 17) appear in Spanish.

Born to Russian Jewish parents in Buenos Aires, Pizarnik spoke Yiddish and Spanish at home, and acquired French at school. Early on, she was very clear about what she wanted in life: “I would like to live in order to write. Not to think of anything else other than to write. I am not after love nor money. I don’t want to think nor decently build my life. I want peace: to read, to study, to earn some money so that I become independent from my family, and to write.”[1] Several years later, in her 1965 essay “The Incarnate Word,” Pizarnik wrote,

That assertion of Hölderlin’s that “poetry is a dangerous game,” has its real equivalent in several famous sacrifices: the suffering of Baudelaire, the suicide of Nerval, the premature silence of Rimbaud, the mysterious and ephemeral presence of Lautréamont, the life and work of Artaud. … These poets, and a few others, are linked by having annulled — or having tried to annul — the distance society imposes between poetry and life.

brigham hadn’t published a poem prior to her inclusion in El Corno Emplumado at age fifty-two. That lack of publication had nothing to do with the quality or magic of her poetry and everything to do with brigham making what she wanted to make and doing so in her own time. In Robert Yerachmiel Sniderman’s “Pre-Face: ‘what do we fear/losing the things a man loves/shelter,’” a great meditation on brigham’s life and poetry, he writes of Mondragón and Randall asking brigham, after hearing her read her long poem “Yaqui Deer,” if they could publish it in El Corno Emplumado. brigham initially declined. “By that time,” Sniderman notes, “she had written at least two book-length poems, two collections of poetry, and one 700-page novel.” Add to that information this terrific exchange from a 2012 interview at Guernica with brigham’s champion, C.D. Wright:

Guernica: In Cooling Time, you write that you “contest those writers whose end is (reviling-all-the-way) to prevail” and you give us the stories of several writers who decline to self-promote. What’s the goal of a poet like Besmilr Brigham who won’t publish except on the insistence of someone else?

C.D. Wright: Well, Besmilr Brigham did publish quite a lot. She happened to be uncovered at a point when the magazines were scouring for women. She was, however, sought out only for about a decade. She lived a rural, itinerant life. It didn’t mesh with having a “career.” She had a calling.

What I know to be true is that brigham and Pizarnik had a calling in common, no matter when their respective callings were realized. I point this out not to devise a commentary on age in general, or the age by which one should do or should have done something, but to confirm that linear life’s a ruse. brigham and Pizarnik stand as guides whose restlessness and bravery I recognize and am reassured by, guides who’ve accompanied me through darker junctures, guides whose lives I’m drawn to. I was twenty-one when I first read brigham (Run Through Rock: Selected Short Poems of Besmilr Brigham, edited by C.D. Wright), thirty-five when I first read Pizarnik (Extracting the Stone of Madness: Poems 1962–1972, translated by Yvette Siegert). While reading brigham, I was on the verge of leaving a large town for a city; while reading Pizarnik, I had recently moved from a small town to a city. At each of these critical turns, I wanted badly to be moved by something that had nothing to do with a geographical move.

When I read poetry that works on me, when I feel thinking, there’s a kind of tension that originates at my collarbone and makes its way to the base of my skull before worming upward to rest in my face. In moving so, that tension becomes a warmth, and that warmth sometimes elicits tears. For instance, this line from Pizarnik’s “Primitive Eyes,” first published in 1971’s A Musical Hell, is the epigraph of a lifetime: “I write to ward off fear and the clawing wind that lodges in my throat.”[2]

Here I am late into age thirty-six reading of Pizarnik’s life, of her death by Seconal overdose at the same age in 1972. (The arrival of this kind of information always happens like so: you’re about to leave one age for the next, and instances of, say, writers who died at one age or the other present themselves. Rimbaud died of bone cancer at thirty-seven.) And in processing the information of Pizarnik’s death, I think of “Blue Asian Reds (For Roadrunner),” one of the best songs on Terry Allen’s Lubbock (on everything), a record I’ve listened to regularly over the past few years. There’s a Texas connection here: brigham grew up in the Rio Grande Valley. I love this excerpt from her biographical entry in the Fall 2014 issue of Kenyon Review:

… raised by farmers in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas, began writing seriously in Arkadelphia, Arkansas, traveled alone by freighter in 1948 to charred Europe, from 1950 to the mid ’70s with daughter and husband traveled by car to and lived in Nicaragua, Nova Scotia, Alaska, Honduras, Guatemala, Mexico, returning in intervals to the US to work, writing relentlessly “putting away manuscripts” on her own terms

On her own terms, in her own time, not to think of anything else other than to write, I want peace. In Spontaneous Particulars: The Telepathy of the Archives, Susan Howe says, “In research libraries and special collections words and objects come into their own and have their place again. This known world.”[3] When I read besmilr brigham and Alejandra Pizarnik in El Corno Emplumado, this known world is reconstellated with the work of two women whose losses to history would have meant great losses to poetry.

1. Patricio Ferrari, “Where the Voice of Alejandra Pizarnik Was Queen,” The Paris Review, July 25, 2018.

2. Alejandra Pizarnik, Extracting the Stone of Madness: Poems 1962-1972, trans. Yvette Siegert (New York: New Directions Publishing, 2016), 103.

3. Susan Howe, Spontaneous Particulars: The Telepathy of the Archives (New York: New Directions Publishing, 2014), 59.

The Little Magazine in America Collection at University of Denver Libraries