We cover our girlish faces. We are the war.

“In the absence of a licit space for the captive female’s desire, it too, becomes engulfed as crime.” Saidiya V. Hartman, Scenes of Subjection

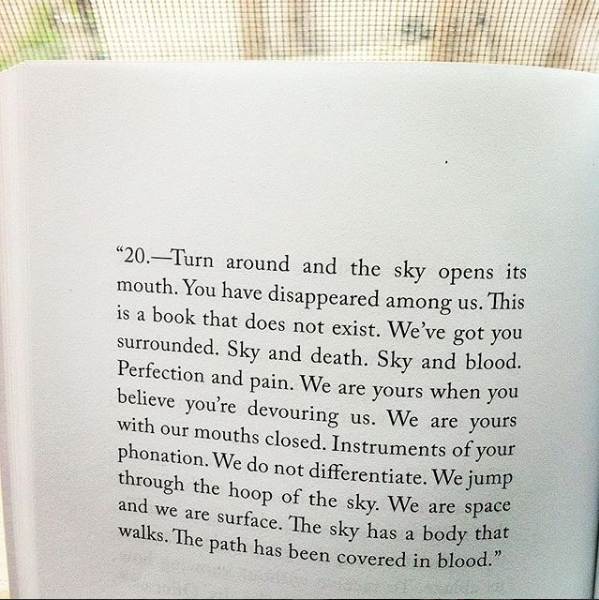

I began to write: Style by Dolores Dorantes slashes fuchsia through structures of totalitarian authority and gendered domination. A swarm of girls declares (with their erotics, not without their erotics, that outermost fastener to sociality which is first to be disturbed, dismantled, deactivated, deadened or rerouted by overt acts of domination and prosaic paths of power), “We will blossom without your consent.” This blossoming makes war, or is war —“We are the fresh fruits of war.” The liveliness of the girls shoots way up beyond any concept of “survival.” Their efficacious energy volleys violence back in the language of desire. My theory there, swimming up through slick black obsidian black light obliterating black ruffled feathers of traumatic experience, is that survivors of social violence get their social radiance disturbed, their social legibility obscured. The very thing which connects, communicates, exchanges, seeks out, and secures inclusion in networks necessary for survival — self possession — is challenged. Taking away a person from their body is also casting out that person from the social world, even if just for a moment. We could conceive of Style as a dress cinching the absolute abjection of social vanquishment with the perfect waist-defining sash: a way to clothe bare life.

This insurgent book can be contextualized within the phenomenon of femicide (or feminicide)[1] in Juárez, Mexico. It is defined as gender-based murder, and cannot be separated from US economic domination of Mexico and control of its border. In Juárez, maquiladoras occupy a legalistic liminal zone near the border, unprotected by full labor rights. Dorantes worked as a journalist in Juárez and wrote Style during a transitional period just after her subsequent exile. The book rebounds life force appropriated by transnational domination and the subsequent chaotic situation of the drug economy there. “We will blossom fruits of blood. Trees of ash.”

Saidiya Hartman writes critically on the narratives of “seduction” during slavery. The word is exploited as an “alchemy that shrouds direct forms of violence under the ‘veil of enchanted relations.’” She goes on, “The intimacy of the master and slave purportedly operated as an internal regulator of power and ameliorated the terror indispensible to unlimited domination.”[2] The narrators of Style speak back from this imposed predicament using their own needs, desires, their undead or unkillable libidinal energies to plot the ending. In supernatural anti-lyric, they beg and sexually threaten a male authority, intoning enough power to overcome his life. This can be read as a style of survival and a fighting style which leverages the force of domination like a boomerang.

In Juárez, the femicides are ritualistic, horrific, and accompanied by sexual violence. From Terrorizing Women: Feminicide in the Americas: “violence is aggravated under conditions of social exclusion, nonexistent citizenship.” The inextricability of the female body from the aesthetic turns any representation of femicide into potential spectacle. Race intensifies this. Writing on femicide risks redoubled alienation through a tendency to summarize from above without emotion nor stake. I did not feel this way amidst the work of Rita Laura Segato. She refers to the narcos (drug lords) challenging the Mexican government for sovereign power over the territory and population of Juárez. From her essay “Crimes of the Second State”: “The victim’s control of her body space is expropriated. For this reason, it can be said that rape is an act par excellence of Carl Schmitt’s definition of sovereignty: unrestricted control; arbitrary and discretionary sovereign willpower whose condition of possibility is to annihilate equivalent attributions in others and, above all, to eradicate the power of these as alterity indexes or alternative subjectivities.” She goes on, “In the language of feminicide, the female body also signifies territory … the woman’s body is annexed as part of the nation that is conquered.”[3]

With its taunting, sexual, and threatening lyric of white-hot energetic overcoming, Style offers an alternative lexicon for surviving. There is that word — survival — here meaning literal survival, but always also pointing to the murderous potential of any interpersonal or sexual violence. Cassandra Troyan writes,

Post-sovereignty is then an image of the subject who has already been killed — brutalized through illness, poverty, sexual violence, white supremacy, colonialism, genocide, misogyny and suicide — but refuses to die, by the need to bear witness. The articulation of these practices in the poetry of traumatic histories situate the body as the site of discourse, yet it is not a body as identity. It is a body of resistance, bodies of refusal, bodies which say, — you have killed me but I am still not dead.[4]

Dorantes draws upon the awful cultural storehouse of images of the (“beautiful,” female) victim. But her scapegoat does not ask for a Levinasian gaze, one which depends on the another to say, yes, you are human, I grant you that with my gaze. It is a performative revenge lyric embedded within a social equation. The lyrical “I” is a feminine swarm, a dissimulating mass, and the “you” is a male authority. The book might be called posthumanist. It seethes with exhilarated and otherworldly resentment, drawing energy from social forms — beauty, fetishized femininity, formalized sexual play — to enact a spell for the once-killed to regain liveliness.

Exploitation and force are foundational structures of the West’s self-reproduction, and archived in the Western imaginary. Playing with these things enables one to cope with power, to be, as Lauren Berlant says, “a mass of incoherent things and not be defeated by that.” She asserts, “Training in one’s own incoherence, training in the ways in which one’s complexity and contradiction can never be resolved by the political, is a really important part of a political theory of non-sovereignty.” In this thinking, art is delinked from worldmaking, yet grounded in the political.

Style was originally published in Spanish as Estilo in 2011, then translated by Jen Hofer for a 2016 bilingual edition.

1. See the Guatemala Human Rights Commission’s factsheet.

2. Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1997), 92.

3. Rosa-Linda Fregoso and Cynthia Bejarano, eds., “Terrorizing Women: Feminicide in the Americas,” (Duke University Press, 2009).

4. Cassandra Troyan, “Post-Sovereign Poetics: Resistance in Traumatic Violence” (paper, Panel 2: Biopolitical, Post-Sovereignty, Post-Recognition Poetics, POETICS: (The Next) 25 Years, Buffalo, New York, April 9, 2016.

The Unproductive Mouth