VIVA CADA!

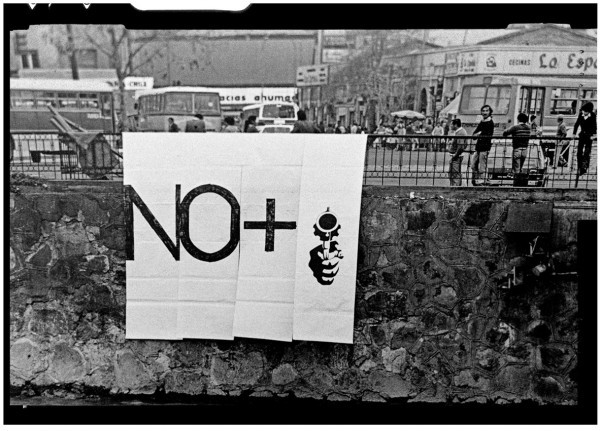

Halfway through the 60s, art in Chile had developed mainly on two fronts: one with a critical and international vocation that included the experiments of conceptual art, and another, more committed to the political context. When the military coup happened in 1973, political art was completely removed from the picture. Pinochet’s dictatorship began to impose a regime of censorship and persecution, which strongly affected the local cultural scene. With many artists and authors imprisoned, tortured, assassinated, and exiled, the national artistic production was practically paralyzed. Around 1977, when the most brutal part of the dictatorship finally ended, the first signs of artistic renovation appeared, closely linked to conceptual art, performance, body art, happenings, and land art. So that’s how in 1979, the visual artists Juan Castillo and Lotty Rosenfeld, the sociologist Fernando Balcells, the writer Diamela Eltit and the poet Raúl Zurita got together in order to fund an influential artist collective that will become one of the most representative group of the so-called escena de avanzada.1 The CADA (Colectivo Acciones de Arte/Actions of Art Collective) showed up with the determination to strongly influence the reformulation of the Chilean artistic discourse, while generating an active work capable of problematizing the relation between art, politics, and the city. Occupying poor neighborhoods, mass media, international organizations (such as ECLAC), and art galleries, their actions constantly expressed a desire for sociopolitical change and were based on the purpose of intervening in Santiago’s urban space with images that questioned the conditions of life in Chile under the dictatorship. From sending milk trucks from a dairy factory to the national Fine Arts Museum; dropping leaflets about the relationship between art and society from civilian aircrafts; staging hunger strikes inside a small metallurgical factory; to inviting artists from different fields to fill the walls of Santiago with the graffiti/message “NO+” (“No more,” which later on was completed by common citizens according to their particular social demands), CADA conceived the city as a museum, the society as a group of artists, and life as a work of art, feasible of being corrected. As Raúl Zurita recalls, “during those years everything was banned. There was no congress, no political parties, no unions, no student federations, so art and poetry were in charge, they had a responsibility. Both were the most radical way of expression. They were always bordering on political action and were always inviting to contempt, to non-submission and not resignation. It was one of the most creative times of Chilean Art.” Even though CADA was not exclusively a literary collective, its influence in current writing and artistic practices (and even in political activism!) is unprecedented and has no boundaries. Its legacy still prevails. Take for example the “affair” that occurred a couple of years ago in a reading given by Raúl Zurita for the Poetry Foundation in Chicago (details here and here.)

So this is how this series on Chilean Poetics begins. Remembering CADA.

___________________________________________________________________

1. Escena de Avanzada or Chilean Avant-Garde was the name given to the work of artists and writers developed after the coup d’état in Chile.

Chilean poetics