Recovering 'Memorial Day'

Ted Berrigan and Anne Waldman, “Memorial Day” (26:33): MP3

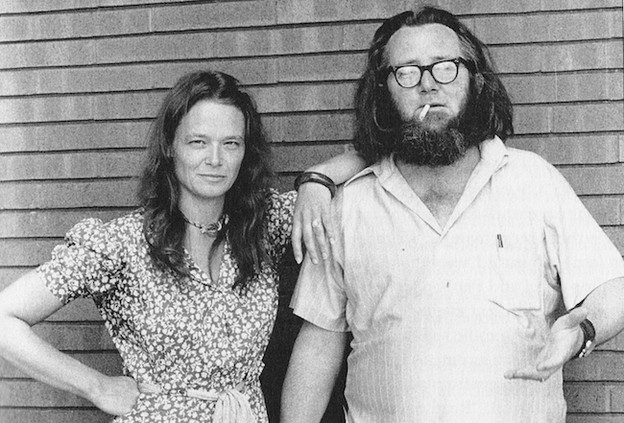

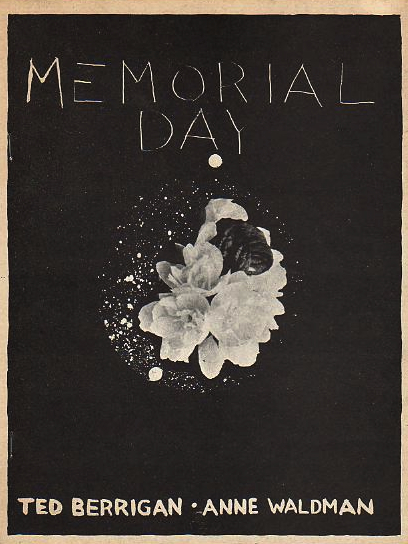

Today at PennSound we’re marking the Memorial Day holiday in a distinctly poetic way, by unveiling a long lost recording of Ted Berrigan and Anne Waldman’s “Memorial Day” from a May 5, 1971 reading at the Saint Mark’s Poetry Project.

This new addition to the PennSound archives is notable not only because “Memorial Day” is a landmark collaboration between two of the New York School’s finest poets, but also due to the rarity of the recording. Berrigan and Waldman only read the poem together and in its entirety once — in fact, “Memorial Day” was composed specifically for their joint reading in the spring of 1971 — and while the event was recorded, it would seem that the tape had been missing for several decades, presumably lost forever.

Everyone seems to agree that Berrigan had obtained a recording of the reading from the Poetry Project, with most believing that that he’d stolen the sole master copy from the archives. Alice Notley observes, in the notes to The Collected Poems of Ted Berrigan, that he “listened to it obsessively … continu[ing] to learn from this collaboration for many years.”[1] Ron Padgett picks up the story in his 1993 book, Ted: A Personal Memoir of Ted Berrigan:

Ted built up quite a personal collection of audiocassettes of poetry readings by himself and by poets he liked. He kept them in a typewriter case in the living room at 101 Saint Mark’s Place, the same room he wrote in. One morning not long before his death, someone came in through the fire escape window, picked up the case, and walked past the sleeping Ted and Alice and out the door. My heart curls up every time I imagine the thief dumping all those cassettes in a trash basket somewhere.[2]

Were there other tapes? Ostensibly yes, but they’ve never emerged. In correspondence over the years, I’ve learned that neither Notley nor Padgett had copies and that the recording was missing from the Poetry Project archives. Anne Waldman reports that she once had “a recording of a recording of a recording” made by Clark Coolidge but that it’s either in her archives at the University of Michigan or otherwise lost. A five-minute excerpt from the reading (half of which is the authors’ very entertaining opening banter) appeared on her 2001 CD Alchemical Energy — Selected Songs and Writings and was a very early addition to PennSound’s archives (uploaded in March 2004), and its clipped voices and relatively poor quality attest to the effects of multiple generations of reproductions. In spite of its incompleteness and low fidelity, the recording is a touchstone for fans of the two poets — I see, for example that Jed Birmingham and Kyle Schlesinger have linked to the recording on the Mimeo Mimeo blog today — and it’s exactly for these reasons that this new, complete and much cleaner tape is worthy of celebration.

We have Robert Creeley to thank for the version we’re releasing today, as it was discovered among his massive collection of reel-to-reel tapes that Pen and Will Creeley were kind enough to donate to PennSound for digitization. Over the past few years, we’ve shared many incredible and often one-of-a-kind recordings from Creeley’s archives, the size and breadth of which attest to his tireless love of poetry, and within this body of more than one hundred tapes, “Memorial Day” opted to remain mysterious and hidden until the very end. Somewhere along the line the reel had gotten separated from its proper case, and it was only uncovered in the final batch of sundry tapes we processed. Knowing full well about this recording’s somewhat mythical status (I wrote about Berrigan’s stolen tapes in a 2009 essay on his 1979 collaboration with Harris Schiff, Yo-Yo’s with Money) I will own up to both teary eyes and a jittery burst of adrenaline when I recognized the familiar voices while listening through the otherwise unmarked file. Today, thanks to the gracious permission of both Alice Notley and Anne Waldman, I have the great pleasure of sharing that experience with you.

. . .

Questions of rarity notwithstanding, “Memorial Day” is a breathtaking poem that shows both Berrigan and Waldman at the very height of their early, New York School-inspired styles, which were ripe for evolution. The poem’s community focus, collaborative nature and performative aims are all quite evident here — at least a dozen of their friends and compatriots are mentioned and older pieces from both Berrigan (The Sonnets’“XXXVII” and lines from “Things to Do in Providence”) and Notley (sonnet “22” from 165 Meeting House Lane) are folded into the composition — and according to Notley, one of the poets’ key goals in writing “Memorial Day” was “to include other voices” (685). We also see this in the appropriation of rock lyrics from a variety of sources including the Byrds’ “Draft Morning,” the Velvet Underground’s “I’m Beginning to See the Light,” the Beatles’ “Hello Goodbye” and Mississippi John Hurt’s “Talking Casey” among others (Waldman’s refrain of “let it down / let it down on me,” for example, might originate in George Harrison’s “Let it Down” or the McCoy’s “Hang on Sloopy”) and these pop culture citations are very nicely complemented here by the poets each singing one section of “Memorial Day” (a pre-arranged constraint), with Waldman joining Berrigan in heartbreaking harmony on the repeated entreaty, “Oh Lord, / have mercy.”[3]

Fittingly enough, “Memorial Day” is largely a meditation on death: its inevitability, its effects on those who survive, and the need to carry on with the weight of this knowledge. “The angels that surround me / die // they kiss death / & they die // they always die,” Berrigan observes in the poem’s opening lines, and Waldman counters, “they speak to us / with sealed lips / information operating / at the speed of light … we speak all the time / in the present tense at the speed of Life” (289). Five years after his tragic Fire Island accident, Frank O’Hara’s absence still looms large in the New York scene and it’s he who most actively haunts “Memorial Day” — Berrigan recalls first meeting him at the Met and visiting his grave, while Waldman mourns the recent death of her cat, a direct descendant of O’Hara’s. Other deaths and near-deaths serve as emotional anchors within the poem as well, most notably the war wounds and eventual passing of Guillaume Apollinaire (whose grave Berrigan also visits), along with the tale of Tuli Kupferberg’s unsuccessful suicide attempt made famous in Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl.”[4]

Fittingly enough, “Memorial Day” is largely a meditation on death: its inevitability, its effects on those who survive, and the need to carry on with the weight of this knowledge. “The angels that surround me / die // they kiss death / & they die // they always die,” Berrigan observes in the poem’s opening lines, and Waldman counters, “they speak to us / with sealed lips / information operating / at the speed of light … we speak all the time / in the present tense at the speed of Life” (289). Five years after his tragic Fire Island accident, Frank O’Hara’s absence still looms large in the New York scene and it’s he who most actively haunts “Memorial Day” — Berrigan recalls first meeting him at the Met and visiting his grave, while Waldman mourns the recent death of her cat, a direct descendant of O’Hara’s. Other deaths and near-deaths serve as emotional anchors within the poem as well, most notably the war wounds and eventual passing of Guillaume Apollinaire (whose grave Berrigan also visits), along with the tale of Tuli Kupferberg’s unsuccessful suicide attempt made famous in Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl.”[4]

As is the case in readings of Ginsberg’s masterpiece, Berrigan’s retelling of Kupferberg’s non-plussed reaction to his non-death is one of the poem’s best laugh lines, and throughout “Memorial Day,” we see the gravid inescapability of death tempered with humor. When asked for his thoughts on death, Joe Brainard observes with Warholian aplomb that “Well, / you always get / lots of flowers / when you die” (302). Bernadette Mayer, who “had to arrange her mother’s funeral age 15,” and whose subsequent loss of her father and other family members in her earliest years led her to believe that “that’s what people do” offers Waldman a tongue-tripping list of dozens of causes of death for inclusion in the poem: “tuberculosis, syphilis, dysentery, scarlet fever and streptococcal sore throat, diptheria, whooping cough, meningococcal infections, acute poliomyelitis, measles, malignant neoplasms . . .” (301-302). Of course, it’s Berrigan who provides the most memorable line when, thinking of O’Hara’s epitaph, “grace to be born and live as variously as possible,” tells us:

I told Ron Padgett that I’d like to have

nice to see you

engraved on my tombstone.

Ron said he thought he’d like to have

out to lunch

on his (299).

More than forty years later, the poignancy of “Memorial Day” is greatly amplified by all those celebrated in the poem who are now gone, including Kupferberg, Brainard, Joe LeSueur, Edwin Denby, Jim Brodey, William Saroyan, Ray Bremser, and even Bette Davis. Of course, no absence is more acutely felt than that of Berrigan himself, who succumbed to complications of cirrhosis on another uniquely American holiday, July 4, 1983, and was (due to his service in Korea) given a military burial in Long Island’s Calverton National Cemetery. Immediately preceding “Memorial Day”’s stunning final litany of closures, there’s a wonderful exchange between the poets that seems even more fitting in retrospect. Berrigan confesses:

I am the man who couldn’t kiss his mother

goodbye.

But I could leave.

& so I left.

& now, on visits, we kiss

Hello, Goodbye.

& I have no other thoughts about it, Memorial Day (310).

to which Waldman offers a benediction:

O you who are dead, we rant at the sky

no action

but pain in the heart

& a head that don’t understand

the meaning of “heart” or “have heart”

or

“take heart”

She is walking away with herself

away from despair

she’s that lucky girl!

graceful, &

complicated head

(heart)

*

Who’s keeping me alive

& what

I praise the lord for every day you & you & you & you & you

& you & you & you

Brothers & Sisters

You are with me on Sweet Remembrance Day (310-311).

Those of us alive to relish this new recording have the privilege of joining Waldman in a new “Sweet Remembrance Day,” connected to all of those we’ve loved and lost, as well as those who survive to carry on their memories.

1. Alice Notley, Anselm Berrigan, and Edmund Berrigan, eds., “Notes,” The Collected Poems of Ted Berrigan, (Berkeley: University of California, 2005), 686.

2. Ron Padgett, Ted: A Personal Memoir of Ted Berrigan (Great Barrington, MA: The Figures, 1993), 58.

3. Ted Berrigan and Anne Waldman, “Memorial Day,” The Collected Poems of Ted Berrigan, 308.

4. It bears mentioning that despite Ginsberg and Berrigan’s perpetuation of this poetic urban myth, Kupferberg was seriously injured by his jump off the Manhattan Bridge and took great pains to ensure that other wouldn’t follow in his steps.

Editor, Jacket2 and PennSound