Poetry vs oil: Round one

Canada’s Tar Sands has a problem (irony alert: there are no end of problems with this nasty stuff)—it’s not easy to get out of the ground and out of the country to the “world market.” Right now, one major pipeline carries the goop to Vancouver’s Burrard Inlet, where it is loaded onto supertankers tourists can wave at from scenic Stanley Park. The proposed Keystone XL pipeline, south, to Texas, has been (temporarily, perhaps) blocked. So now there are plans for a “Northern Gateway” pipeline to carry massive amounts of crude over 1,170 kilometers of forested and river-crisscrossed Northern BC—to the still largely undeveloped coast of the Great Bear Rainforest. Charming.

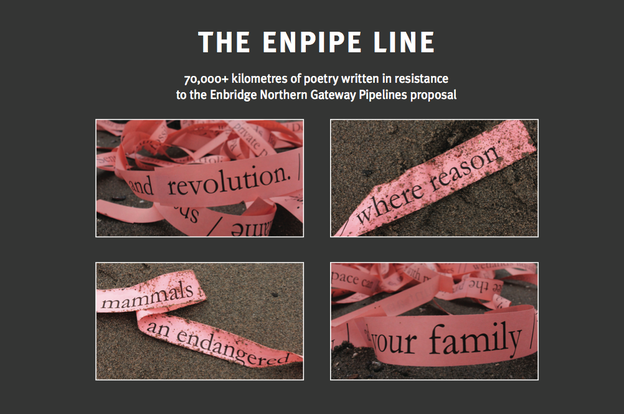

Into the fray steps a poetry anthology—The Enpipe Line (Creekstone Press 2012)—edited by a diverse collective that includes poet/activist and project founder Christine Leclerc (full disclosure: I am a contributor). Originally conceived as a 1,170 kilometer long line of collaborative poetry (matching the proposed pipeline’s length), the project eventually grew to over 70,000km. The poetry in it is diverse, to say the least, and includes contributions from widely published and recognized poets to children and “professional” activists (such as Greenpeace co-founder Rex Weyler). The poetry comes in all sorts and forms (lyric to conceptual); some contributions read like short, compressed essays, others like screeds against capital, still others are in fact songs, chants, and laments. More than simply a pipeline is addressed: corporate exploitation of the environment thrashes about these poems in all its shapes and guises.

Here’s an example of the range. Eleven-year old Ta’Kaiya Blaney of Sliammon First Nation wrote the song “Shallow Waters” (the performance of which has become a popular mainstay of demonstrations in the province over the past year) when she was ten:

In shallow waters, I can’t see

Your clear waters lapping at my feet

The lifeless ocean, black not blue

I didn't help but deep down I knew

Place this beside lines from "The essentially liquid nature of wetland landscapes," Ecopoetics editor Jonathan Skinner's contribution:

wetlands liquify the Lockean tenets of labor and land

ownership

wetlands liquify the ownership society

wetlands liquify states’ rights

wetlands liquify eminent domain

Finally, to get a sense of the “overlapping” of poetry and resistance this anthology enacts, consider the fact that many of the contributors have signed up (along with some 4000 other British Columbians) to speak at the government’s touring Environmental Review Panel (coming to a town near you throughout 2011/12), on which occasion many of them will read their contributions to the anthology. How will these occasions be read? As “poetry readings”? “Protests”? “Presentations”? I hope, and think—all of the above. But something other than we usually expect occurs when poetry steps outside the marked space of the “reading,” outside even the “demonstration,” and into the bureaucratic domain where corporation and government perform their absurd dance of death and profits.

From a purely aesthetic viewpoint, some readers might find some of the work in this anthology “lacking.” However, the precise point this anthology raises—the very fact of the concatenation of art and revolution that it works—is the disappearance and impossibility of the “purely aesthetic” in today’s world. Rex Weyler, writing in the Forward, asks—“Can poetry stop ecocide?” I would have to answer no. But I would also say—it’s not not going to stop it either. Poetry is inescapably “part of [the] public resistance” to the pipeline, poems “arrows in the public’s non-violent arsenal” (Weyler again). It’s not, as we sometimes assume, that poetry is simply an ineffectual “weapon” in the social realm. It’s all a matter, really, of where you aim it, and the occasion/zone in which you let loose your volley.

Neighbouring zones