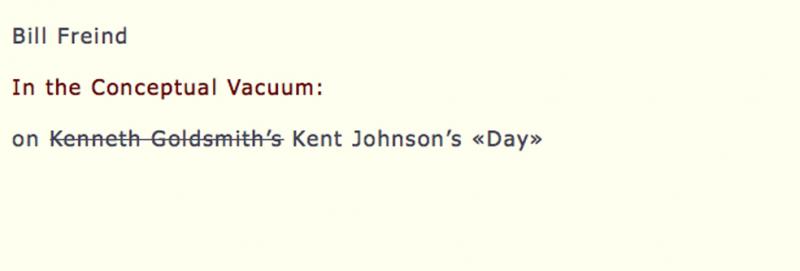

Bill Freind on Goldsmith's 'Day'

From Jacket #40 (late 2010)

I am writing a review of Kent Johnson’s Day although I haven’t read a word of it. That’s not a problem, since Johnson’s Day is identical to Kenneth Goldsmith’s Day, which is itself a transcription of an entire issue of The New York Times from left to right, ignoring the divisions between columns, articles and advertisements. In fact, Johnson’s Day is an actual copy of Goldsmith’s Day, with stickers of Johnson’s name covering Goldsmith’s name, as well as some jacket blurbs from Juliana Spahr, Christian Bök, and “Kenny” Goldsmith himself. Not surprisingly, the blurbs from Spahr and Bök were originally for Goldmith’s Day; the blurb attributed to Goldsmith is Johnson’s riff on various comments Goldsmith has made on Flarf and conceptual poetry.

However, I haven’t read Goldsmith’s Day either. Although I consider myself a big fan of his work, I’ve read almost none of it. (I made it through about 50 pages of Soliloquy, his transcription of everything he said over the course of a week, and thought it was brilliant.) I suspect that, like me, a lot of people who appreciate Goldsmith’s work haven’t even seen it, much less read it in its entirety. And that doesn’t matter: as Goldsmith has suggested, his writing is so conceptual that it’s unnecessary to actually read what’s on the page. Just as Duchamp’s ready-mades presented a challenge to what he called “retinal” art, Goldsmith’s work effectively posits a non-retinal literature. “Uncreative writing” prompts some essential questions about the nature of art, and while Goldsmith is obviously (and admittedly) revisiting the same questions posed by hundreds of different artists throughout the twentieth century, repackaging the avant-garde still carries a certain charge.

That’s not a cheap shot, especially since one of the central qualities of Goldsmith’s work is its belatedness. Yesterday’s news, traffic and weather reports are clearly untimely, but so is the entire premise of Day: because the circulation of print editions of newspapers was already plummeting in September 2000 when Goldsmith began the book, he commemorates a medium whose significance was headed into the recycling bin of history. Goldsmith’s own medium is similarly (and, I think, intentionally) belated: the physical size of his books echoes the magna opera of Anglophone high modernism such as Ulysses and Finnegans Wake, the Cantos, Maximus, “A.” But that comparison is wonderfully absurd: instead of Pound’s extraordinary and often appalling conception of history or Joyce’s dazzling and encyclopedic vision, we get a semi-coherent transcription of an outdated newspaper.

Read the rest of this article.