The phonotextual braid

First reflections and preliminary definitions

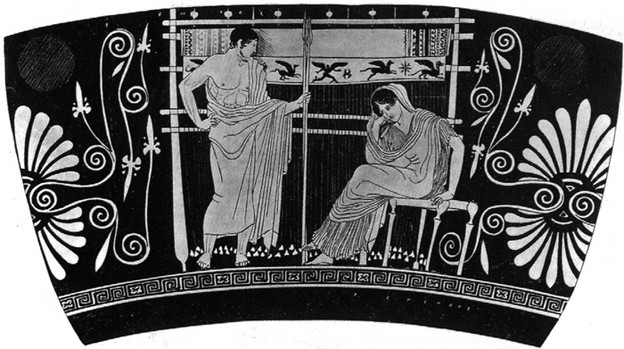

The notes that I’ll be contributing to this space over the next few months will be devoted to the Penelope-like task of weaving and unweaving what I call “the phonotextual braid,” that intertwining of timbre, text, and technology that presents itself to us when we attend to recorded poetry.

My objectives are to distill some of the thinking I and others have done on the topic, especially in the years since the launch of PennSound, to test some of the hypotheses and habits that have guided that inquiry to date, and to wonder aloud about the directions phonotextual studies might productively take in the near future. I also have in mind to share some real-time reading notes on a recent double issue of the journal differences devoted to “The Sense of Sound” and to poke around in the sonic archive of the 1980s in advance of a conference that my colleagues at the National Poetry Foundation and I will be hosting this summer.

To define the phonotextual object as a threefold braid of timbre, text, and technology is already to reduce it — as a moment's reflection on any of the component terms will demonstrate — but more than a Hegelian penchant for triadic presentation motivates my choice here. For even if each strand of the braid reveals itself to be a multiplicity in its own right, rich in historical and phenomenological complexities that deserve (and usually have indeed already received) independent treatment, there is a certain heuristic value in holding such complexity in abeyance just long enough to entertain the thought that our object — the phonotextual object — may exhibit emergent properties not entirely explicable by reference to its constituent parts and thus stimulate us to pose new questions, as well as older questions anew, about it.

By way of getting started, a few words about each strand of the braid:

Timbre

I will use the term “timbre” to organize a set of reflections on “the voice” as it is encountered in recorded poetry. Initially at least I’ll accept a definition that errs on the side of naiveté in hearing the voice as an sign that indexes — before, alongside of, and beyond other meaning-making — the condition and situation of the body that produces it. To err on the side of indexicality, immediacy, and physiological (if not necessarily psychological) individuation is to hear “voice” as rhyming with “noise,” specifically the noise emitted by the human animal situated somewhere along its trajectory toward death, in a condition of finitude shared out along the (by tendency asynchronic) spectra of physical dis/ability and social dis/enfranchisement. The necessary corrections to this initial standpoint aren't very hard to formulate: the voice, after all, is more than a physiological given; it is subject to as many modes of making (of poiesis)as it is simultaneously the object of many modes of training (of technê). Moreover, timbre can no longer credibly be conceived as preceding texts and technologies that are later derived from or applied to it. The seeming immediacy of “the voice” is — to use the kind of dialectical formula beloved by Adorno — itself a mediated effect.

Text

One way of approaching the phonotext is as a translation from the graphemic domain (marks on a page) into the phonemic domain (noises in the air) as “witnessed” — which is to say simultaneously altered and preserved — by a recording device of some kind. In this scenario, the text is anterior to the voicing of it and the voicing is anterior to the scenes of technologically-mediated audition that the recording makes possible. It is important to remember, however, that many kinds of performance practice demote or dispense altogether with the anterior text (a typical scenario for so-called “sound poetries”); that sound-engineering practices shift the function of the recording device from the passive registration (as in the “field recording”) to the active generation of new textual permutations; and that technologies for the reconversion of the phonemic to the graphemic (e.g., “machine transcription”) have been extant for some time and will soon become ubiquitous (making it relatively easy, for instance, to automate the process of transcribing every sound file hosted at a site like PennSound). The field of textuality is further widened when we take into consideration the kinds of "paratextual" evidence that Gerard Genette called attention to in Seuils (1987; translated as Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation in 1997) — making the necessary adjustments for his print-based orientation — and the many discourses of framing, describing, and rendering “findable” (including through the generation of “metadata”) that are meant to make archives and databases intelligible and navigable to their users.

Technology

The secular miracle of separating a sound from its source, storing it, and releasing it into a new spatio-temporal context has by now become so routinized that it is hard to remember that we’ve only been able to reliably perform it for a little less than 150 years. The technologies by which this feat has been accomplished are numerous and constitute a complex series in which acoustical gains and losses are seldom separable from economic ones. One consequence of the hyperactive cycle of innovation/supercession that stretches from Edison to our times is that specific recording and playback devices (and indeed entire “formats”) become “vanishing mediators,” as when a track on first released on phonograph is taped to reel-to-reel, then dubbed to cassette, duplicated several times, and later converted from analog to digital before being uploaded as an mp3 to a server like Ubuweb or Pennsound and downloaded by an individual user to iTunes. Though the spectral timbres of the superceded technologies can, on occasion, be heard in the digital “delivery instance” (to update a term out of Jakobson) — as when the distinctive sound of a stylus traveling a groove less than frictionlessly can be heard in one's earbuds—for the most part we're content to discard such data without a second thought, just as we discard the signifiers on our way to “understanding” messages in ordinary discourse. I’m not sure we're wrong to do this — after all the decay of one phoneme is the precondition for the emergence into audibility of a next — but I am curious to know what a commitment to investigating the technological (along with the authorial) provenance of phonotexts might contribute to our ability to situate, evaluate, and intrepret them. And I'm even more curious — because my starting point is even more ignorant — about the possibilities for analysis and interpretation opened by advanced computational instruments that promise to quickly and exhaustively identify salient features of the phonotext that an individual interpreter could in the past easily have spent hours compiling. How might technologies for pre-treating and graphically presenting phonotexts supplement our practices of “reading” them? And in what ways might they come to transform those practices?

*

As I trace out some of these threads in the coming months, I hope that those of you who share an interest in the subject will feel free to be in touch. J2 commentaries do not automatically allow for direct response, but I am always happy to receive them (my contact information can be found along the right-hand sidebar) and will from time to time gather up and include them in this space.

The phonotextual braid