Tom Devaney

March 23, 2014

I can't get started (PoemTalk #61)

January 8, 2013

Why apples can cause riots (PoemTalk #51)

March 22, 2012

Ill, Angelic Poetics (PoemTalk #48)

December 19, 2011

A few good words (PoemTalk #29)

Kit Robinson, "Return on Word"

March 3, 2010

Living with terror (PoemTalk #23)

Cid Corman, "Enuresis"

October 5, 2009

Surpassing things we've known before (PoemTalk #15)

Lyn Hejinian, "constant change figures"

March 9, 2009

Finally, the group agreed that the poem is about words’ value, seen through the dystopia of their devaluation at the hands of economic sectors in which referential certainty is guaranteed to get carried away – in which a good (profitable) year is anticipated by, maybe even determined by, the right people in the room thinking up just the right dead language for the moment.

Finally, the group agreed that the poem is about words’ value, seen through the dystopia of their devaluation at the hands of economic sectors in which referential certainty is guaranteed to get carried away – in which a good (profitable) year is anticipated by, maybe even determined by, the right people in the room thinking up just the right dead language for the moment. Back in 2001 the people of the Kelly Writers House wanted to bring

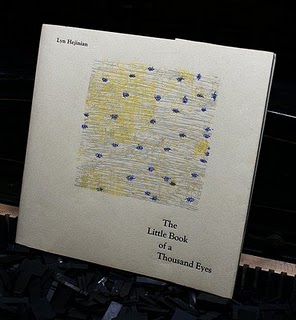

Back in 2001 the people of the Kelly Writers House wanted to bring  It is one poem in a series Hejinian has been writing, a project she currently calls The Book of a Thousand Eyes. If it is finished (perhaps, she tells us, in the summer of 2009?), it might consist of 1,000 poems; more likely of 310 or a few more of them (the number she had completed at the time this episode was recorded). Some poems in the series appeared in The Little Book of a Thousand Eyes, published by

It is one poem in a series Hejinian has been writing, a project she currently calls The Book of a Thousand Eyes. If it is finished (perhaps, she tells us, in the summer of 2009?), it might consist of 1,000 poems; more likely of 310 or a few more of them (the number she had completed at the time this episode was recorded). Some poems in the series appeared in The Little Book of a Thousand Eyes, published by  We agree that from the time of her great Stein talks* and of Writing Is an Aid to Memory Lyn Hejinian has conceived of writing itself, an act that is at once a matter of forgetting and remembering, as a definition (or an "aid" to the redefinition) of the past.

We agree that from the time of her great Stein talks* and of Writing Is an Aid to Memory Lyn Hejinian has conceived of writing itself, an act that is at once a matter of forgetting and remembering, as a definition (or an "aid" to the redefinition) of the past.