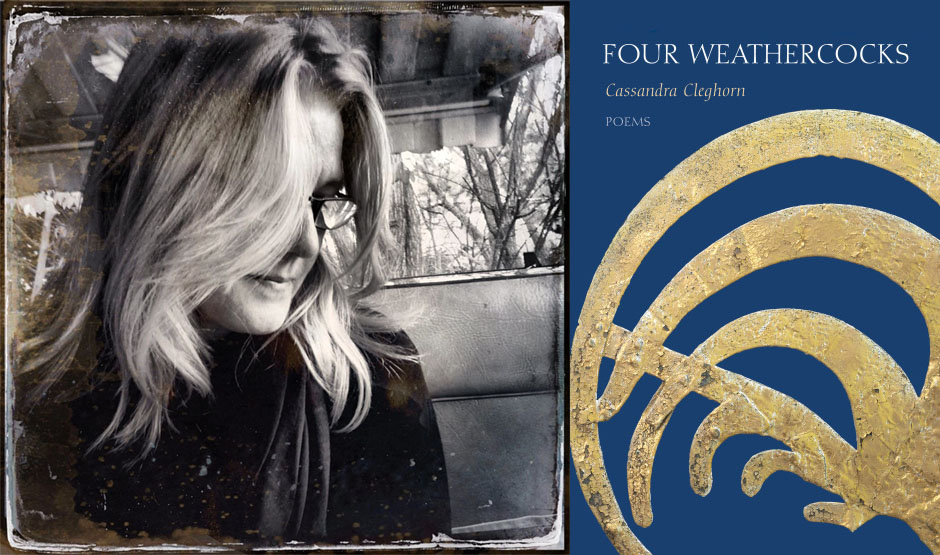

Cassandra Cleghorn's 'Four Weathercocks'

The shapes in “Macondo,” which open the first section of Cassandra Cleghorn’s first collection Four Weathercocks, are obscure and drenched in oil. As they wash onto shore “flayed and stifled,”[1] they are pushed and pulled by the tide, but never named. We are given wings, feathers, pouches, and “a black eye bright in a face of black sheen,” but never the species. Even their heartbeat goes undefined, appearing as a “small throb” pinned to the speaker’s lap. Meanwhile, “lost farmers” spread straw along the shoreline, trying to soak up the oil. Their repetitious scattering and raking is mesmerizing, but not frenetic. The damage has already been done, and the witnesses to this unfolding disaster appear resigned to the consequences:

Opened my arms to what

moved my way, wings half-spread,

brown feathers now black, slack pouch

sealed shut, one web pulling through the crude (7)

In her notes, Cleghorn reminds us that Macondo is the fictional town from Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, but is also the codename for an oil prospect near the site of the 2010 BP oil spill on the Louisiana coast. This is less interesting than the tone set by the poem’s lyrical dissonance, and the way it mirrors the grief held up by the rest of the collection: transfixed rather than urgent, the poem moves at a contemplative pace quiet enough to let the world pass through. The lack of frenzy is surprising, considering what appears to be at stake for everything involved.

The collection opens with the epigraph poem “Chiasmus,” an examination of the detailed plant photographs taken by early twentieth-century German photographer Karl Blossfeldt. As in “Macondo,” we are given the outline of these objects — here, various titles of Blossfeldt’s photographs — but never the specifics of what they contain:

arrayed in grids, some dissected

so far from their given forms

as to be mineral or animal (3)

This deliberate obfuscation moves Cleghorn’s meditations about the natural world into the metaphysical. Blossfeldt investigated the structure of plants by magnifying his images, sometimes up to thirty times, until his stems turned into towers, or, as Cleghorn writes, “CHESTNUT SHOOTS aren’t just phallic, / they’re actual cocks!” (3). Because the rhetorical figure of a chiasmusrepeats concepts in reverse order, this anthropomorphism tampers with the known Western binary of human control over nonhuman counterparts. And yet:

Both plants strain to be themselves

in space, the sensing spills into

the sensed (4)

This spilling over is a refusal to ignore the ungrounded force of the natural inside our domestic spaces. Instead, this is a shared space where fires burn underground (with no attempts to stop it), a man floats over Los Angeles in a lawn chair, “tilting slightly, / tethered to forty-two weather balloons” (11), and two sisters give up a child for adoption to a couple who will “lift her, comfort her / before the toy runs out of song” (52). If you place these stories next to the image of a weathervane, or weathercock, moving with the wind, the narratives of grief become emblems of resilience. This is the “small throb” experienced at the beginning of the book, signaling an internal and ecological struggle to come to terms with what we’ve created, what we’re passing through, and what we can’t control.

The two poems at the end of the first section, “To Saint Hubert, Wonderworker of the Ardennes, Patron of Hunters and Mathematicians, Protector from Rabies” and “Milagro,” epitomize this struggle. Until the twentieth century in some parts of Europe, if you were bitten by a dog with rabies, you might have used a metal “key” in the form of a heated nail, cross, or cone to cauterize and sanitize the wound. This charm, called St. Hubert’s Key,[2] was endorsed by the church. In “To Saint Hubert,” the speaker crosses the path of a “woozy” raccoon with “eyes molten, fish-pale,” and calls to St. Hubert for help:

Nick me, cut this tongue’s

thin anchor, heat the nail head (15)

There is no attack, only anticipation. Or, as with the “Macondo” shapes, our attention is around the periphery of the event. What matters more is the relationship between the objects. To be bitten by animal and turned animal is to tamper again with the binary that separates us from the natural world. The preindustrial approach to rabies — a combination of home remedy and prayer — might seem quaint to modern eyes, but it worked. It also showcases our fear of transformation, where the “sensing spills into / the sensed,” forcing us to concede our power over the natural world. When the speaker begs, “Keep me keep me”(15),it’s a fear of crossing over, of losing.

In “Milagro,” there is no crossing over. The object speaks directly to the reader from its place on the other side of human experience. In parts of Mexico, the southern US, and Latin America, milagros are found in places of worship and take on various forms.[3]While the form and shape of Cleghorn’s embodied milagro are unclear, the location is identified in the first stanza: a “cathedral whose interior reaches / cannot be taken in” (17). From this space the milagro watches “clusters of people / doing things together” with cold, wistful observations:

I believe but cannot prove

that the sun will begin to lower

later today than yesterday.

May one less soul plummet

in this hill-town tomorrow (17)

What does it mean when the object we put faith in fails to give us the answers we hope for? In “Milagro,” there are no promises for the people gathered “in a circle or in a line knee to knee” about what comes next — only the solace that comes through prayer. In “To St. Hubert,” the saint is evoked, but what are the results? The truth is, we already know the extent of our shapelessness. But as this book reminds us, over and over again, that doesn’t stop us from holding vigil.

1. Cassandra Cleghorn, Four Weathercocks (Detroit: Marick Press, 2016), 7.

2. George Fleming, Rabies and Hydrophobia: Their History, Nature, Causes, Symptoms, and Prevention (London: Chapman and Hall, 1872).

3. Eileen Oktavec, Answered Prayers: Miracles and Milagros Along the Border (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1995).