Reading weed acts

A review of Carol Watts's 'Dockfield'

Dockfield

Dockfield

Carol Watts’s Dockfield opens with an epigraph from Emily Dickinson — “Like Rain it sounded till it curved.” This attention to sound and structure also informs the opening lines of the first poem:

Step through on a curve,

a grand elliptic.

I will find you. Always.

A message sent up from simple frequencies.[1]

In many ways, the structure of this poetry is parabolic. Points of reference are plotted along a curve that eventually returns to the same site of origin — the dockfield — before continuing onward. This is reflected in the release and retraction of words and images within parts of lines as well as in the broader sweep and curve of deep, transhuman time to which the text aspires. In the later poems, as the pace of crisis picks up, and images of ecological horror stumble into each other within a dervish of lyrical speaking over and silencing, there is still an inevitable return to the still center of the dockfield. From the very beginning, this is a text that is fundamentally about the anxiety of language, of “leav[ing] without echo” and the inheritance of silence and “unstated things” (1). When Watts calls upon a “we” or exhorts one to “[s]ay it” (1), she discloses the anxiety of forging a precarious community in the absence of language. For there is no one to say it to, and no one to say it at all. It is a haunting portrait of annihilation in the Anthropocene, of bodies hollowed of language and landscapes evacuated of bodies. Even in this expanse of seeming nothingness, of scattered points on the far-reaching “grand elliptic,” Watts’s language is one that discloses desiring, a repeated invitation to speech and assertion of “hereness” that transposes an implicit “you” upon the “I” through an intimacy addressed from alienation. Later, landscape and bodies are bound up in a gradual knowledge — “My desires are puffed with fleshy presence, or peace / by which I mean the variegated absences” (7). To seek this emplacement is to know it through repetition, a movement across the wide reach of space that is retracted as “[t]he binding of docks keeps them rooted in / a wildness of alignment” (7). Later, the sweep of wind across the dockfield is both planetary and “like the cross-hatching of skin” (9). This is an erotics of hold and release, of desire and death.

Watts constructs the trope of the dockfield as a site that both contains and is in excess of a cluster of ecosystems.

I am docked. Is that to say ready to load

or unload

at some vestige of homecoming.

It’s unfamiliar ground.

Perhaps it is the area of water between. (3)

It is a dockyard where ships come to straddle the liminality of oceans, with their ghosted histories of colonial passage and contemporary commerce complicating ethical questions of shelter and homecoming. With the language of weedy invasion, the dock recalls the “settler injury / of this order” (5). It is the both an agricultural and discursive field of meaning; Watts writes, “Continual expectation of harvest catches you on the other side of / outcome. // In its grain is illusion of inheritance, the ache of / election denied” (8). Here, the trope of the dockfield troubles a realization of global food scarcity and the complicity of the political language of climate change in this. It moves from the dead, dense air of outer space to the living strata of soil and undergrowth. The collection plays astutely on the various interpretations of the word “dock”: it interrogates prospects of justice by bringing poetic language to the dock; examines cohesion and attachment through the possible image of a space shuttle being docked; and paradoxically, also queries forms of truncation and disruption by placing itself around the weedy ontology of dock leaves. Etymologically, “dock” then evokes the astral, botanical, aqueous, judicial, technological, and somatic. Watts brings a granular ethics of attention to these cross-hatched landscapes through a lens of deep time.

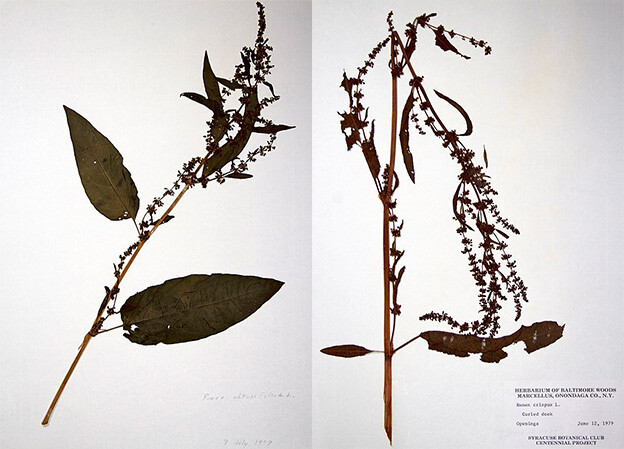

Amongst the compression of interpretations that the presence of “dock” in the text facilitates, perhaps the most prominent is the botanical one. A family of weeds whose leaves carry both medicinal and food value, but members of which (broad-leaved dock and curled dock) were declared injurious and invasive under the Weeds Act 1959 in the UK, “dock” signifies the richness of contradiction and systemic exchange within these poems. The “government report” disavows complexity — “[t]here is no alchemy but simple injuriousness (5)” according to it. Instead, the text surface is both bristled by this injury and is its own salvage, yielding the production of a composite, evolving botanical subjectivity as the sections progress.

Or am become a new genus (coarse weedy plant)

with broad cool leaves, collected like a balm.

For stings and itches. (3)

Both the gesture towards “genus,” with its attendant problems of classification — the old dock newly reconceptualized but vulnerable to further recategorization as “invasive” — as well as the use of “am” to indicate a composite beingness that applies to variations of poetic and dock subjectivity, recall the engagement with decategorization that we see in Timothy Morton’s work. In “Queer Ecology” in particular, he looks at how the decategorizing turn within ecology interacts with queer politics to move away from binaries (human/animal, biological/technological, human/nature, man/woman, animal/plant) and instead lends itself to the making of composite ecological things.[2] Watts’s reading of the much wider context of ecocidal harm within contemporary politics is achieved through similar moments of attention towards an entangled, exchanging subjectivity.

For Watts, the dockfield is a site of Anthropocene drama captured within a cinematic sweep of deep time. The gaze is cinematographic in its prismatic contemplation of “light’s bitter throwback” (4) and use of rapid sliding frames of motion, stasis, and transformation to hold bodies and forms in suspension at the edge of crisis. Organs mutate “but they lacked / discernment” (6), species disappear, poems are formed and unformed within a wide lens that captures the accretion of change through an acceleration of destructive time. Throughout this and the entire collection, there is a grappling with the anxiety of adjudicating the adequacy of available language while talking about ecological crisis.

It is a time of lies.

Extinctions mount each day with birdsong.

Pismires gather on planetary scale

to carry themselves forward.

My limbs become conglomerations of small wills.

The land blooms in formic extension

as if forest emissions delegated dramas

to scrubby undergrowth.

A field left to itself. (6)

The dockfield almost appears to be elided by the Anthropocene signature but is caught up in lyric action. Can the lyric ever speak of the enmeshed self and ecological trauma meaningfully? Does it constitute moral resistance to the culture of political silence on the subject of climate crisis? Dockfield facilitates but does not resolve these questions of the complicity of form in shaping the relationships between the inside and outside, text and blank space, body and environment. The dock leaves perform “weed acts” (5) — they signify disruption, sustenance, and spilling over; they defamiliarize landscape and official language; they ungrid readable spaces because “[g]reen veins occupy fertile ground / wither their own palmy lifelines” (5). They go against state directives of power and territorial control. For a collection that powerfully and obliquely alludes to political failures and collateral violence in its specter of exploded cities (10), witches “caught in malevolent thickets” (2), and the haunting prolepsis of cities drowning in a flood that acts as a contemporary ecological reiteration of an ancient collective trauma (14), this is a critical mode of ethical interjection. There is an excess of fertility in this postmodern wasteland (“Grass grows beyond plaint. // It seems a sign of luxuriousness, so all is not yet up / with fertility” [11]) as the poet withholds, offers, and satirizes plenitude in a “scarcity [that] is nonetheless replete” (8), particularly at the close of the text, where she writes: “So much faith in abundance, sounding” (16). As “the dockfield stirs” (15), it opens a moment of possibility and of stasis abandoned. The dock leaves persist outside the reach of the text, “[a]mong the horsetails, vetch, plantains, scarlet burnet, on this / poverty of ground” (15), as lichen in a postnuclear heap or saxifrage flowering in the ruins of Blitz-ravaged London — the complex punctuation of Watts’s experimentation in a new, entangled provisional postpastoral.

In Dockfield, language is transient and residual like a snail track or the carbon from a burnt city. It is fossilized in the complex time of deep space, wielded to ossify falsehood into accepted knowledge, atrophied through human history to finally insist on a new lyrical and political intimacy between bodies and nature. This is language at an edge, sharply recalling its materiality, like “[s]pikes of seeds are dry and purple, rusted / memorials to the season just past” (8). Watts exhorts a series of speech acts that appeal to localization of “hereness” and “thisness” and being. Bodies, trauma, and language are intertwined such that one becomes the function of the other. She writes: “Dock // A cut tale” (3). A truncated narrative is superimposed on the image of the docked tail as violence begets silence, the dock becoming the material and signifier of absence.

Throughout the text, the official language is one of falsehood, injury, stuttering, and silence. A longing for an Edenic return via the erasure of error and species is quietly satirized; in this neopastoral, a “natural” origin story can only be conceptualized through a technological register — “During the rebooting of relation we assume / a fantasy of beginning once more” (7). Watts’s use of virus as a metaphor later is particularly compelling when read in conjunction with the lines: “I began to see human violence as viral inoculation, at cost to all of / us. // It is not clear what the body is that the violence seeks to save” (10). The use of virus evokes both the biopolitical associations of the negotiation of a culture of death within a community (or more widely here, ecosystem) as well as the dissemination function of the linguistic mode of something “going viral” within a contemporary technosphere.[3] The virus, like the dock, contains both its injury and its relief — it compromises as well as inoculates. Watts writes: “Small things refuse to break through, and populations give out” (11), recalling both viruses and weeds and asserting a precarious repression that can only fail when confronted with the interruptive grammar of either.

The consequences of this historical trajectory emerge in a sustained exploration of and through sound, framing the political complicity and uses of various forms of language within the world around the dockfield. “If these are late days, then action might seem purer / where words are kinetic. // Their elastic collisions equal to a world without heat / or noise.” (12). This is a soundscape infiltrating an evacuated landscape, an imperfect and fragmented superimposition that demands new forms of knowledge and habitation. The identification of hearing as a mode of “biological accommodation” a few lines later is particularly fertile. While there is no formal demonstration of experimentation in sound, white noise, and silence and its resulting disorientation, the reference to accommodation does suggest a possibility of echolocation, of an exploratory emplacement. The absences and presences of objects within an environment form a linguistic network that produces a new hybrid subjectivity, a composite of plant-animal-human-discourse. Watts plays with scale, drawing the dockfield into a tight focus, activating a microgrammar “where / spores are silences” (12). This is an ethical unspeaking of the pursuit of official “truth” in collision with botany where the edges of weeds, the “[s]mall medicinal shadows in darts and spikes,” mark the “future shapes of words” (4). A web of pronouns emerges from this concatenation of sound and silence from anxious, querying subject positions.

There is an experimental “I” and a fragile community of pronouns running through Dockfield, all caught within the tangle of a weedy poetics of body and leaf. “I lived by a dockfield once. / Now my thighs grow shady recompense for hurt” (3). From quite early in the pamphlet, the fragile “I” that is bound together by the reiterative power of speech acts, both preserved and abraded by the friction of space and time, comes to acquire a botanical consciousness by virtue of proximity. In the state of being docked, an overdetermined occurrence with undercurrents of being rendered vehicular or unlawfully transgressive or broken, the “I” becomes the “coarse weedy plant,” its own hurt as well as solace. There is a more difficult question of instrumentalization here that Watts does not fully resolve. The “I” as the docked ship is demonstrated to be doubled in contradiction; it is both the container and the contained with a critical distance between the lyric self and the object under scrutiny. But where the “I” approximates the dock plant, despite the existence of a bristling hybridity, there is also simultaneously a greater tendency to assume knowledge on behalf of a vital ecological other. At the very end of the poem, there comes the problematic certainty inherent in the assertion “[t]he dockfield knows this” (16), a totalization of subjectivity and lyric fixity that the rest of the text resists. Empathy is complicated by mere identification in a reiteration of what Donna Haraway might consider the “human exceptionalism” that is inherent in the very concept of Anthropocene.[4] In particular for Watts, where the human “I” extends weedily to claim an epistemological certitude for the dock plant, the text makes a lyric return to the problems of complicity in political and ecological harms that it critiques elsewhere.

This cyborg “I” meshes the somatic with the botanical, right down to the cellular intimacy of expanding vacuoles and “whorls and patience” (8). It is a woody and weedy subjectivity, disrupting surfaces, negotiating scarcity and plenitude, and is half embedded in the flourishing plant excess of a postdisaster landscape. The poet attests that “[t]he curiosity of weeds is one condition of survival. // Abetted by birds, excreta of mammals, shaggy / pelts and airborne potentials” (13). This weedy epistemology then takes the form of a richly entangled somatic intertextuality that proposes a disavowal of margins that goes beyond a simple relationship of interdependence.

This commitment to undoing neat categorization is formalized in the typographic boundary work of the collection. In this sixteen-page pamphlet, the position of page numbers could ambiguously function both as an indicator of the page itself or a demarcation of a new section in the poem. The text can then be read either as a long continuous poem or as consisting of sixteen discrete sections, each moored to the limit of a single page but such that contemplations, fragments, and images from one leak out into other, later poems. This is writing that alludes to being liminal and fluid but that is held together provisionally within constraints of typography and interpretation. There is a gentle negotiation of boundaries within a collection that draws its strength from a sustained and complex consideration of hybrid bodies, anxious speech acts, and vatic poetic vision. In the midst of this unfamiliar and disorienting pastoral is the invocation of the dockfield, a site of linguistic, environmental, and political crisis that is precariously stabilized across multiple poems through a persistent insistence. Dockfield is a densely textured composition that deconstructs the anxiety and grace of emplaced bodies as part augury, part lyric, part choreography mustered through time travel.

1. Carol Watts, Dockfield (Cambridge, UK: Equipage, 2017), 1.

2. Timothy Morton, “Queer Ecology,” guest column, PMLA 125, no. 2 (2010): 273–82.

3. For a reading of the “immunization paradigm” of politics and why liberal states preserve a form of death-making function within themselves as inoculation from greater harms of illiberalism, see Roberto Esposito’s Bios (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004). While Watts does not attend to the political proximities between forms of ecological and social violence in tremendous detail, Dockfield could be read alongside Esposito for a further complication of the presentation of nonhuman bodies under duress.

4. See Donna Haraway, “Tentacular Thinking: Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene,” in Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016).