'deer flesh to human flesh'

On C. R. Grimmer's 'The Lyme Letters'

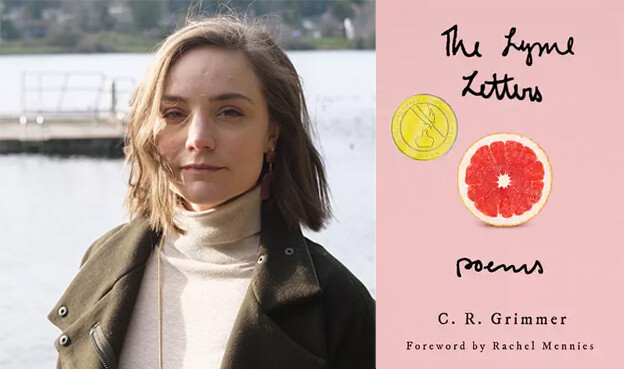

The Lyme Letters

The Lyme Letters

C. R. Grimmer’s debut full-length collection The Lyme Letters uses epistolary form to document the character R.’s navigation of their life as a person with chronic Lyme disease. R., Grimmer’s brave and thoughtful nonbinary femme protagonist, addresses the poems to their doctor, their therapist, their dog and cat, and to a series of intimate composite beings whose appellations each repeat as the title of multiple poems: “My Dearest of Pyramids, My Fisher of Logical Men & Teddy Bears,”[1] for instance, or “My Dearest of Horsemen, Wonder Boy of Stoves,” (8, 34, 52). Grimmer’s epistolary poems variously ask for help, grieve, remember, articulate desire, and trouble a personal archive of approaches to and languages of authority: medical, religious, interpersonal, and institutional.

The poems strive to find words for queer and nonbinary people living with chronic illness by resetting the medical and religious language for being and knowing in which R. has been steeped. Important to R.’s letters, however, is that they do not reject this religious and medical language. Instead, they use the letters to splice themself into that language and to share this new lexicon of being with their rotating set of addressees.

In the letters, R. also uses this new language to ask for care from systems that respond only with limited ideas of cure. Throughout the collection, R. grapples with how to negotiate with inhospitable and often damaging forms of gatekeeping and bureaucracy that stand in the way of the care they need, from loved ones as well as from medical systems. While some of the collection’s letters offer fragmented and intensely sensory lyrical reflections on desire, intimacy, and loss, others offer straightforward instructions, as R. coaches their doctors on how to write accommodation letters.

In one of several poems entitled “My Dearest Dr. xxxx,” Grimmer writes:

Could you please provide a note of accommodation for me at work? I struggle to connect, to keep up, etc. It would look something like this:

Exhibit A — Sample doctor’s note when requesting accommodations (to be submitted to the Office of Workplace Diversity on the doctor’s letterhead) (15, emphasis in original)

In this and other poems, R. advocates for themself against the expectations of restrictive ideas of illness and disability. Their experience echoes what disability advocate Eli Clare describes as a system in which “for now, doctors inside the medical-industrial complex are the reigning experts, framing disability as a medical problem lodged in individual body-minds, which need to be treated or cured.”[2] R. works to disarticulate their relationship to a desire for cure from cure as a rhetoric used to catalyze inadequate and often problematically normalizing forms of medical treatment. As Clare notes, “cure is inextricably linked to hope,” an orientation that guides R. through their bureaucratic negotiations.[3]

R. endeavors to form a relationship with cure on terms that exceed and lay bare their internalization of pathologizing experiences with doctors and psychologists. In “My Dearest Mountain, Living Memory & Master, My Text,” Grimmer writes:

I am trying your suggestion: ‘The Aporia of the Performative Cure for Lyme’

…

Act (B) or Illocutionary:

My Doctor-Authority

urged me to believe I could get

better so I would get better (12)

…

We dance around

a ring and suppose,

but the Cure sits

in the middle and knows (13, emphasis in original)

As a means of negotiating R.’s relationship to the idea of getting better, Grimmer reframes the minor Robert Frost poem “The Secret Sits” to address not secrets but cure as what the people in R’s. life rotate around. What Clare would refer to as Grimmer’s “grappling with cure” shapes R.’s search to find meaning and desire beyond cure but also to reframe cure on their own terms.

As R. looks for other forms of language that describe their experience as a desiring and attentive neurodisabled person with chronic illness (we learn in the letters that R. is a person who has been diagnosed as bipolar), the language of queerness offers one mode of identification. In one of several poems entitled “Hewn,” Grimmer writes:

Becoming beast is the sales pitch

queering offered

Becoming queer is the sales pitch

beasting offered (40)

R. identifies the experience of being infected or of being changed by a nonhuman animal as “beasting,” becoming differently human and differently connected to the nonhuman as a result of the tick’s bite. As R. comes to terms with their experience as a queer and nonbinary person with a chronic illness caused by a nonhuman animal, they experiment in the letters to find language with which they might form a new epistemology that importantly includes nonhuman relation.

R.’s search for new language for their being as it is informed by kinship with the nonhuman suggests the complex relationship between queerness and the nonhuman that Jack Halberstam considers under the framework of “wildness.” As Halberstam writes, “Wildness is neither utopia nor dystopia; it is a force we live with and a way of being that we are organizing out of existence. If the wild has anything to tell us, it is this: unbuild the world you inhabit, unmake its relentless commitment to the same.”[4] In the poems, some instances of that unbuilding identify the speaker not only as kin with the nonhuman but also as bodily merged with nonhuman beings. In one of the poems entitled “My Dearest of Horsemen, Wonder Boy of Stoves,” Grimmer writes of R., “Today I am moss. Yesterday, tides. Is it growth? To spread outward & / down?” (8).

Many of Grimmer’s poems return to the scene of infection to document how the meeting of body and tick was for R. always already a scene of kinship with the nonhuman and also a scene of queer desire. In one of the poems entitled “My Dearest Family Members, Blood Co-op & Never-Ending Transfusions,” they write:

Some of the campers----mainly girls-----like to tease each other with scratching fingers and say, ticka ticka ticka ticka. The ritual does not prevent the ticks from leaping: deer flesh to human flesh. Some swear that deer & human blood taste same-red-smell-ish with pooling heat as tick’s prize. (62)

The tick and the girls are forever linked in R.’s memory. For R., to be infected with Lyme is to make the memory of those girls into a symptom. The memory of the girls flares up with the physical symptoms of the illness, and yet the memory, and how it inflects R.’s sense of sexuality and gender, is beyond what is medically understood as the parameters of illness.

Additionally, many of the poems reframe biblical rhetoric in search of belonging that exceeds the terms of diagnosis and acts as a harbor for queer intimacy with language and bodies. In their repurposing of biblical rhetoric, these poems offer a reparative reading of the rejection of queerness in whose name biblical language is often used. In the poems, Grimmer produces a relentlessly queer engagement with the faith that their repurposed biblical language describes.

Grimmer’s use of biblical language to express a queer sense of faith embodies Melissa E. Sanchez’s argument that “faith, in short, turns out to be a profoundly queer concept, one that disrupts stable understandings of desire, identification, and subjectivity.”[5] In several instances, R. rebuilds biblical language so that they might belong to it. In “My Dearest of Hairy Companions, Mon Chien Blanc,” they insert themself into the opening chapters of the first verse of the Book of John: “‘In the beginning she was / the WORD, & she was in / the WORD, & the WORD / was her’” (77). Throughout the collection, the poems use the speculation inherent in faith to gather the hope and desire necessary for survival. As Sanchez posits, “to practice faith is to doubt much of what we see and to believe in what we don’t.”[6]

Sanchez’s description of faith echoes Zakiyyah Iman Jackson’s discussion of reassessing “how we ‘know what we know’” as a necessary component of critical inquiry. As Jackson argues, “Epistemology is a problem not of the past but one that is constituent with our being.”[7] Grimmer’s poems are a manifestation of this suggestion — they make and remake R.’s engagement with epistemology as, for them, the most viable approach to living with illness. Finding no way to exist within their received narratives as a queer and nonbinary person with chronic illness, R. remakes language to find a way to be in the world.

The Lyme Letters provides a signifivant addition to recent work in ecopoetics, disability poetics, and queer experimental writing, even as the collection exceeds each of these categories. The poems present a beautiful study in radical openness and a necessary meditation on building a brave, durable, and adaptable selfhood out of pain and misreading of all kinds.

1. C. R. Grimmer, The Lyme Letters (Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech University Press, 2021), 25, 31, 55.

2. Eli Clare, Brilliant Imperfection: Grappling with Cure (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 8.

4. Jack Halberstam, Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020), 180.

5. Melissa E. Sanchez, Queer Faith: Reading Promiscuity and Race in the Secular Love Tradition (New York: New York University Press, 2019), 25.

7. Zakiyyah Iman Jackson, Becoming Human: Matter and Meaning in an Antiblack World (New York: New York University Press, 2020), 8.