Beauty is useless

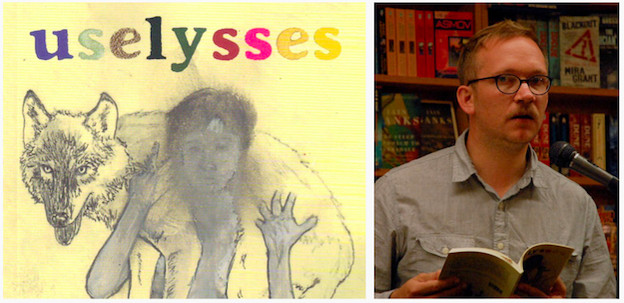

A review of Noel Black's 'Uselysses'

Uselysses

Uselysses

In the Proverbs of Hell, William Blake stated that “Exuberance is Beauty.” In Uselysses, poet Noel Black unravels each word in Blake’s proverb: the beauty, the exuberance, and especially the is. In this unraveling, Black’s poems find nothing too sacred or too mundane. Here, exuberance and beauty are abundant givens (take titles like “Ballad of the Homeopathic Pony” and “Huckleberry Finnegan’s Wake”), but it’s the poet’s subtle inquiry into being — the ontological ground we’re standing on — that drives these poems, and their reader, forward into new terrain. Uselysses candidly traces a journey through space and time, from rural Colorado to New York City and back to the poet’s very birth. Along the way, it manages to ask the most daunting questions about who we are and why we’re here in terms that are simple, funny, and full of a singular voice. The result is a pursuit as heroic as the book’s title suggests.

One of the first things to notice about Black’s work is the valence of the epic lyric merged with that of the delightfully banal. “I wish I had time to work / on my zombie novel / down at the Dunkin’ Donuts / all day long,” ends “In the Manner of Gerard Manley Hopkins, Sort Of,” the first poem in the book. The mind that occupies these poems delights in the full spectrum of its experiences and desires, often tied in with playful idioms: Dunkin’ Donuts, Dr. Pepper, the poet’s son calling the Beach Boys “The Beach Brothers.” The tendency toward play coalesces early in the book with “8 Dead Poets,” a series of tombstone-sized poems that disclose the deaths of canonical poets (Whitman, Dickinson, Shelly …) in their own diction:

Frank O’Hara

“If I had my way I’d go on & on

and never go to sleep,”

said Frank O’Hara just hours before

he got hit by a Jeep. (19)

All eight of these literary giants influence Black in ways that emerge throughout the book. Here, he honors them by building them a new kind of pedestal, one that includes both their genius and their mortality. I can’t help but think it’s what each of them would have wanted. Black’s use of puns and rhymes (“Sylvia Plath / turned on the gath”) makes this poem as memorable as the works its subjects wrote. The section of the book titled “Moby K. Dick” expands on this project by combining the titles and styles of seemingly-disparate works of literature. I laughed aloud at “Miss Lonelyhearts of Darkness” and “The Spy Who Came in from the Cold Blood,” and there’s a beating heart behind the obvious wittiness, evidence of the deepest kind of admiration.

These homages represent a meeting between the book’s main themes: the personal versus the universal, the major versus the minor, what makes a life meaningful — and a death. Seen as a sort of Venn diagram, Uselysses overlaps the sphere of the quotidian with the sphere of the great cosmos, what Charles Simic calls “the secular divine”; the place of intersection manifests as both reverence and humor. There’s a human dialogue with poets of yore who also dealt, coincidentally, with this same intersection.

Like Whitman, Black revels in his multitudes. Despite the simplicity of the poet-narrator’s desires — adventure, comfort, fast food — these poems spring from a complex identity. Many of the poems in the book seem to begin with unremarkable events in the poet’s life, which then set off chains of thought and feeling leading toward something much larger. “‘The Truth Is Right Here,’ / says the little plastic box of tea tree toothpicks,” begins one poem, before carefully investigating why Truth and toothpicks should occur within the same ordinary thing. A few pages later, “Another Poem” starts with “The mysteries of the universe are contained / in a single varicose vein.” Many of the poems in Uselysses that deal with the ordinary and the divine — and the lack of difference therein — were written during Black’s time living in New York City, far in every sense from his native Colorado. Take “Poem on My 36th Birthday”:

I wonder if I ride my bike through Brooklyn fast enough

if the particles of Walt Whitman

would smash into my face

revealing the mysteries of the universe,

which means what — one singing or one seeing? (45)

There’s a dense, searching quality to the New York poems, noticeably shrugged off once Black and his family return to Colorado. Places and travel are significant to this work — San Francisco, Bogota, Crete, Oklahoma. A necessary tension among urban, suburban and rural environs yields some of the most interesting material in the book. Places have particular and almost totemic character that colors everything that happens within them. This character comes across effortlessly. “You’ll take [Ron Padgett] to buy a bowl of potato soup at the Safeway where you learned to shoplift …” stands alongside “You’ll get flashed by a wanker in a park outside Ephesus.” The care taken with places and events confirms a sense of awe at the very fact that we are here on Earth, sharing our lives in the present.

Having lost his father to AIDS, Black makes no secret of his own intimate experience with cosmic impermanence. The generosity around sharing this experience opens up the reader’s awareness of her own most meaningful experiences. Uselysses concludes with a long poem, “Prophecies for the Past,” a series of lushly-wrought “predictions” about what will happen to the poet over the course of his life. Autobiographical details range here from pathetic to outrageous to dazzlingly tender. Throughout the book, Black directly acknowledges the immediate forebears of his poetics — Padgett, Schuyler, Kyger — but it’s the spirit of Joe Brainard that this poem owes its life to. Far from a simple imitation, this reenvisioning of I Remember proves what a wild journey a single human life can be.

Uselysses touches a wide spectrum of sincere feeling, although perhaps the image of a spectrum is too linear. In reading, expect to enter a whole field of feeling, a palpable space, where arousal and boredom interact freely humor and tenderness. Expect to remember what it is to be friends with the dead, friends with the living, and ultimately, joyfully curious about being here at all.