Four source-essays — by Anne Carson, Michel de Certeau, Amy Ireland, Cornelia Vismann — converge here in heavily edited form to delimit a terrain of extremity through their respective themes of gender, glossolalia, alienation, and war.

The sources coincide firstly in the sense that I read them around the same time, printed out on paper. This coincidence of nondisciplined reading produced a question about what concretely connected the four texts — especially as they come from different countries, generations, academic traditions, languages, types of publication, etc. I felt their combined affect to be greater than their parts and sought a way of apprehending this affect nonanalytically.

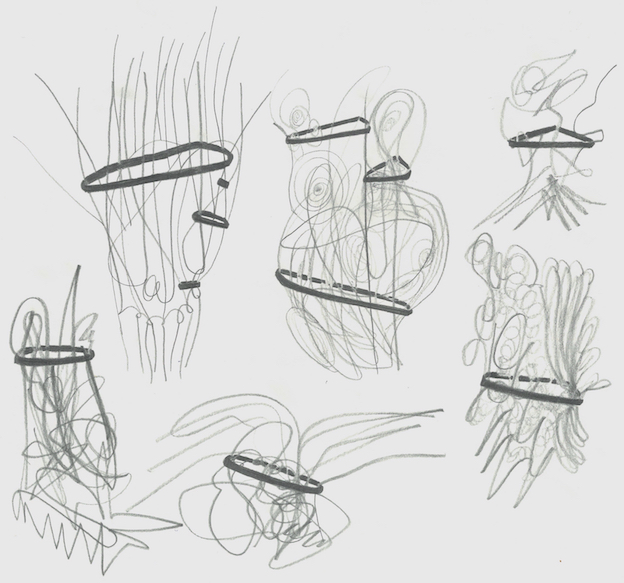

After a time, I returned to the printouts, which I had variously underlined, and commenced the following process (which I reveal here but is far from necessary knowledge):

The first underlined section — that is, individual underlined words or everything contained in a continuously underlined group of words — of each essay is retyped from the printouts into a Microsoft Word or OpenOffice document. Each section is kept distinct from other sections and retains autonomy. This procedure is repeated for the second underlined section of each essay, then the third underlined section of each essay, then the fourth, fifth, sixth, etc., until there are no more underlined sections left for any of the four essays (this happens to be after the twenty-ninth underlined section of de Certeau). This means the essays with fewer underlined sections (probably, though not necessarily, those with fewer words overall), have several “blank” sections, symbolized by §, while other essays continue to unfold. Next, maintaining the author’s word order, each section is formatted into a vertical list of words; all punctuation except capital letters is removed. For each section, when a word appears for the second, third, fourth (etc.) time it joins the line of the first word of its kind. In other words: in each section, the word that appears closest to the top of the list collects beside it each successive word of its kind. With some humor, I refer to the writing protocol described above as “scarcity at the bottom.”

The unpredictable repetition creates a stuttering effect that disrupts traditional reading technique by explicating nonconsensual syntax. My desire while composing “It — subject” was that it become possible for me to read through or across these four essays simultaneously, in order that the affect I mention above become apparent (I couldn’t know how to do or see this in advance of performing the protocol). The words that appear replicated together are inevitably either important to the syntax of the original text or to its content and theme. Everything contained by “It — subject” is latent in the original source — what is most interesting to me is how the results of this procedure make a subtext (subjectivity) manifest that “belongs” to no one.

The numbering system in “It — subject” makes a paltry nod to legal writing. Numbers organize information in a neurotic fashion because they pronounce an order beyond themselves that paradoxically cannot be signified. Numbers signify nothing but empty orders. I am interested in the tension of the subjective and the lexical that the numbering system corroborates. Seeking to induce the banalized paranoia of the present, where words are taken for reality not as its ciphers, “It — subject” insists that neither the writer nor the reader nor the original author can know what has been said. However, in the doing (reading, writing, performing protocol, etc.) of text, there is some knowledge.

What is “extreme” within such a neurotic system is precisely how it could be apprehended as a mild symptom and not the defining paradigm of writing.