Stephen Ratcliffe with Jonathan Skinner

Note: This lengthy conversation between Jonathan Skinner and Stephen Ratcliffe took place in Bolinas, California, on March 22, 2011. Photographs throughout are by Jonathan Skinner.

On progression

Jonathan Skinner: Given that you’ve just finished these two trilogies, do you see a progression through the series?

Stephen Ratcliffe: Oh, yeah. Yeah there is.

Skinner: Was there an intentional progression and is there eventual progression?

Ratcliffe: No. It’s more of a happenstance. An evolution of things. I see in some way what I’m doing now. I began, you know, making incursions toward doing that years ago, but I didn’t know what I was doing. Things I’m doing now are more consciously set, but they actually started a long time ago.

Skinner: What’s the biggest thing you’ve noticed, looking back over it, that’s changed or progressed or happened?

Ratcliffe: Well, you know, there are a lot of changes, really, a lot. For one thing, CLOUD / RIDGE is full of people saying and doing things. But not in these, not in Temporality, nor in this one that’s going on now, it’s up to about seventy-five pages. It started I think January 5th. Although in the first few pages, Johnny [Ratcliffe’s six-year old son] began to appear in there sometime, in early January. Which seemed like, oh, this is really nice … But now he’s not appearing anymore.

I’m still making use of these readings that I do with quotation. You know, finding language in the middle two pairs of lines. It just seems to be getting more honed, and it’s very interesting to do it. I’m pleased with it. I really like these latest ones. But the reference to person A or B … in CLOUD / RIDGE the people are often identified, as “man in black sweatshirt,” “silver haired man,” “man in red truck,” “blond haired woman.” You know. There are these people sort of with epithets. Bob [Grenier] one time commented, years ago, he said, it’s kind of like in Homer: “grey-eyed Athena …”

Skinner: Are these literal people?

Ratcliffe: Oh yeah.

Skinner: So they’re people that are around you. And that’s overheard dialogue?

Ratcliffe: I used to carry these little notebooks around. If something happened, I wrote these things down. And then I would go back and find them and make use of them, but now …

Skinner: Now you’re writing down things that you read.

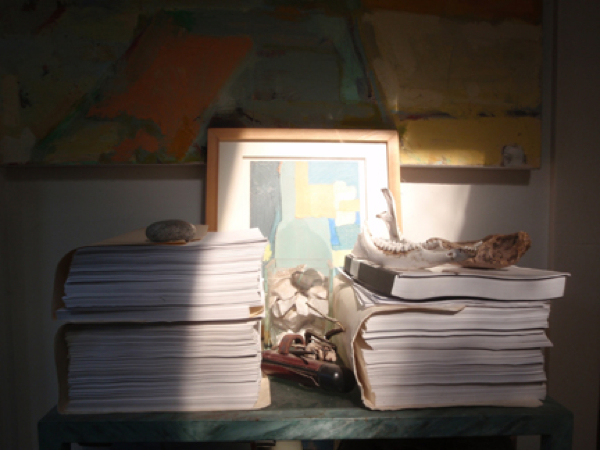

Ratcliffe: Yeah, at night. Like tonight or tomorrow night, I have to go sit down again. And there are maybe seven or eight books. I go through one at a time.

Skinner: Each night you go through each book.

Ratcliffe: No, not every night. But about every five nights, I have to get back to the stuff … I use up all the material.

Skinner: You have to go through all seven of them.

Ratcliffe: Yeah.

Skinner: Pull something from each one.

Ratcliffe: I find a passage somewhere. I go to where I left off and I start reading. I find some words, and I construct them into two lines and I type them on the computer. I put them on the screen so I get the length of the line to be set. And then, when it’s set, then I write it down into the notebook. So, the next day, when I go to compose, to write the poem …

Skinner: Oh, so these are pre-measured units.

Ratcliffe: They’re pre-measured. It used to be that I would just write them down and then I would have to do them on the screen, and it was very hard. CLOUD / RIDGE was very hard to do, because those lines are always shifting.

Skinner: What’s the measure? What determines the measure? Is it a visual …

Ratcliffe: It’s visual, yeah. In CLOUD / RIDGE each poem looks different on the page. It has probably the same number of lines, but arranged in different stanza units. And it’s measured here on the screen but not in the book, so … it was very hard to do, actually. It’s time consuming.

Skinner: You’ve moved from overhearings to a series of readings. But it seems like the practice of observing meteorological phenomena, events in the environment has continued.

Ratcliffe: Weather, ah … yeah.

Skinner: So the surfing is still a part of the constraint, the daily surfing.

Ratcliffe: Yeah, the last lines on the poems now are things written down or seen when I go out in the water.

Skinner: So what are the constraints for Temporality?

Ratcliffe: OK, so I wake up, then I open my eyes, and then I write the poems down in my bedroom. I don’t even get out of bed anymore.

Skinner: Oh you just write them in bed.

Ratcliffe: Yeah, so it’s like what I see out that window. You know, I used to write the poems down here in the kitchen, and there was a lot more stuff to see. But from upstairs, from that higher vantage point, it’s funny, it’s more sky, and less other things going on. So there’s something that’s kind of interesting to me about, ah, moving toward less and less detail.

Skinner: Why?

Ratcliffe: I don’t know.

Skinner: So you open your eyes, and then you look out the window.

Ratcliffe: Yeah, and, ah … here was “The whiteness of moon next to branch,” so that was over, up … [pointing to bedroom window]: “light coming into the sky above still black/ ridge, whiteness of moon next to branch/ in foreground.” That was out there …

it wasn’t exactly at the same time, but it was, basically. And, another curious thing is that there’s this really insistent repeating of the “wave sounding in the channel” …

Skinner: This is what I was going to ask you about!

Ratcliffe: Man! How can that go on …

Skinner: “Insistent” isn’t the right word for it. It’s just … affixed. “Wave sounds in channel!” [Laughs.] I was at the channel today with Donald [Guravich] and I was like, “well, there is the channel in which Stephen Ratcliffe’s wave sounds.” [Laughs.] What’s up with that?

Ratcliffe: I don’t know. I don’t know what it is …

Skinner: I mean I thought that you maybe just decided very consciously that you were going to have one element that would just stay put, like the nail through the note to the wall.

Ratcliffe: No, it’s kind of evolved. You know, years ago there was this “sound of jet passing overhead” that appeared in one of the works, and it appeared a lot. And I remember reading it once in the city. We were doing a reading somewhere … it was actually with some musicians. And one of the guys was a singer: he had a falsetto voice. He was from the music department at Mills, I think. He had an amazing voice, and he kept singing this, in a very high falsetto, or countertenor voice or something: “sound of jet passing over.” It was really striking. And he commented about it.

On performance

Skinner: You did a performance, you did like a fourteen-hour, or somebody did a fourteen-hour performance, of Temporality.

Ratcliffe: Oh, I did. No, Remarks on Color. At Marin Headlands, last May. With some of these same musicians. Not that guy.

Skinner: It lasted fourteen hours?

Ratcliffe: Yes. From sunrise to sunset, on May 16th. Close to the Solstice. It’s about a fourteen-hour day. And there was no sun ever visible. It went from 6 a.m. to after 8 p.m. And we never saw the sun come in. It was totally foggy, and it was freezing in this big gymnasium with the windows open. And most of the time no people there except us doing it.

Skinner: Did people wander in and out?

Ratcliffe: People wandered in.

Skinner: How long did people stay on average?

Ratcliffe: Some might have stayed an hour. Some stayed a little longer. And we did another one, at UC Davis, of HUMAN / NATURE, that was also fourteen hours. It went from 4 p.m. to 6 a.m. Johnny was there, sitting on my lap. In the middle of the night, I was the only person awake, in the whole place. The musicians had stopped playing and they were snoring.

Skinner: And you were just reading.

Ratcliffe: I was reading with one spotlight coming down from the ceiling onto my table.

On process

Skinner: But continuing with the constraints. I’m just curious to get those down. So, you wake up, you look out the window …

Ratcliffe: Yeah, so, the first three lines are written “on location,” in the present.

Skinner: In bed.

Ratcliffe: Yeah, I have this little book, and I write it down. And then I have this other book and I write it down there and then I open up the screen …

Ratcliffe: Yeah, I have this little book, and I write it down. And then I have this other book and I write it down there and then I open up the screen …

Skinner: Oh, wait, so you have two. The first book is just the lines and the second book is the poems?

Ratcliffe: I just started this new notebook. This is what I write the notes in, everything. And then, here’s the whole poem. And these lines have been premeasured, as you say.

Skinner: So the first three lines in the morning. And then the middle part comes from the reading?

Ratcliffe: Comes out of previous readings which have been transcribed into my notebook.

Skinner: Do you do that in a particular time of the day … when you do the middle lines? I mean as far as putting them into the poem.

Ratcliffe: The last time I went into the readings was on the sixteenth. And this morning I did these two sets so I would cross these out tomorrow morning.

Skinner: Ok, so you put those in in the morning.

Ratcliffe: I put ’em in in the morning. And they’re in here. So I just open this book and I transcribe.

Skinner: So what are the last two lines? What’s the constraint for the last two lines?

Ratcliffe: This is what I saw when I was out in the water: “grey-white of fog against invisible ridge, / circular green pine on tip of sandspit”

Skinner: I see. Do you write that in the car immediately after surfing or when you come back?

Ratcliffe: No, when I come back here I remember. Years ago I started doing this when I’d go out maybe at RCA surfing, and sometimes I’d take my little notebook, and as soon as I got up [the cliff] I’d have to write it down. And now I realize, oh, I can remember what it was! So now I don’t actually even compose it. I just sort of see it, I know what it’s going to be and then when I get back I write it down. It sort of has become like second nature.

On surfing

Skinner: Did you surf the tsunami?

Ratcliffe: I did!

Skinner: You did, yeah?

Ratcliffe: Yeah! It was odd. I had to go over the hill for an appointment. So I couldn’t go down there normally in the morning. And I had to take Johnny to school. And it turned out school [which is right on Bolinas Lagoon] was canceled. And I didn’t know it. ’Cause I hadn’t gotten the word.

Skinner: It was canceled because of the tsunami, right?

Ratcliffe: Yes it was. So we came back and about five o’clock we finally went down to the channel. I just wanted to see what it was doing. Actually, I said, we’ll go down and jump in the water. But, the surge … you know, it looked like the tide was going out a little bit, even though it was at just before high tide. And all of a sudden it started to come in, right before our eyes it was going out, and then it started coming in slowly, and then pretty soon it was like a river, racing in. It seemed like it was going twenty knots. But maybe it wasn’t, I don’t know.

Skinner: It was fast, though. It was a lot of volume.

Ratcliffe: Huge, yeah. Anyway, I just ran down the beach and jumped in the water and paddled in.

Skinner: Oh, so you had your board with you?

Ratcliffe: Yeah, yeah, I, ha ha! Some of my friends were out surfing that day and they say it was pretty wild, just the surge going back and forth.

Skinner: A surfer spoke at the symposium on water I just attended in Point Reyes [Geography of Hope: Reflections on Water] about his daily practice of surfing. In the context of the conference, and threats to the world’s water supply, he noted that he wasn’t really doing anything out there and that he sometimes wondered, well, what good is this doing? My immediate thought was: doing nothing might be the best thing to “do,” right now.

Ratcliffe: Ah, that’s interesting.

Skinner: But I was wondering if for you there is a poetics of the practice of time, if surfing is a certain sort of practice of temporality on the board?

Ratcliffe: Yeah. It’s probably hard to put your finger on it, but there is something about … I actually can’t quite explain it, because my desire in writing these lines … you know, if I’m not near the water, if I’m walking around in the city, I can still see clouds, and ridges. I can still sort of find these elements. But there’s something about going out in the water and getting onto the board where your eye is at water level, not walking on your feet, that really shifts …

Skinner: Oh, you mean, when you’re on your belly on the board.

Ratcliffe: Yeah. When I suddenly get onto the board, and I paddle out and I’m just here. It really changes your view of things … there’s something that, ah, shifts. For me now, it’s, you know, no doubt a bit obsessive. [Laughs.]

Last year I got into the water three hundred and fifty-five days. Now this year maybe won’t be as much, because I think I’m going to travel. But here I am on a sabbatical, and I’m hardly traveling. So, I don’t know. But that was my new personal best. Another record set. Most of the time I go out there now, I just paddle. ’Cause I have a bad shoulder.

Skinner: You don’t stand up and surf the waves?

Ratcliffe: No … often I’m just down in the channel. If the waves are good, I’ll go out and try to find them if I have time. Sometimes I don’t have time. But there’s something about getting down at water level, where you’re in the element. And, you know, the board’s going up and down. You get close to these things going on.

Skinner: Well that’s what this Point Reyes surfer talked about, being close to very large animals in the water. Do you become aware of the movement of animals up and down the coast? I mean, do you see animals in the water?

Ratcliffe: Yeah, I saw a seal out there today, you know. Of course you see animals. Birds. Mostly birds.

On the discrete

Skinner: Some readers seeing your poems and not knowing your constraint or location might see “wave sounds in channel,” and they might think it’s like Channel 7. Or, you know, the channel of the brain, like some sort of Jamesian nervous channel.

Ratcliffe: Oh, left channel, right channel. You think? They might just think it’s boring.

Skinner: No, “wave sounds in channel.” It’s fine. It’s definitive. It’s clipped. There’s something about discreteness there. You switch from one channel to the next.

Ratcliffe: I hadn’t thought about that, but, why not, yeah. “Sound of waves in channel.”

On scenery

Skinner: I was wondering about scenery. I was thinking of what you’ve written about Shakespeare, sound and the stage [in Reading the Unseen, Ratcliffe’s book “about offstage action in Hamlet, about words that describe action that isn't performed physically in the play, things we don't actually see”]. And then of SOUND / (system): James’s letters, as the scene of something. And of you on your board, and how what you see stages or frames the poem. What do you see in scenery?

Ratcliffe: Before we discuss Temporality, in this regard, let me say that CLOUD / RIDGE is more chaotic in some sense, although it still …

Skinner: CLOUD / RIDGE has a lot of interiors.

Ratcliffe: … has a lot of interiors and bounces around. In CLOUD / RIDGE there’s also Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse that begins to come in early.

Skinner: Does it take over for the rest of the manuscript?

Ratcliffe: It does. As I’m going through the manuscript now, as much as time permits, adjusting it, it’s quite moving to me. I never had read that book before. In some way I didn’t really read it; I just kept reading bit by bit, and going through it. And I think then I went back when I got to the end and kept going, but, you know, there’s some beautiful passages in there, that somehow connect. They try to connect. In any case, there’s this framing of the beginning and the end with the other things taking place in there. It is a kind of … it’s the scene seen, the seen and heard scene. And the interior lines, the inner lines, are thinking about that, or considering the scene more in language.

Skinner: I was thinking that those insistent, fixed things in Temporality, the “waves sounding in channel,” happen in the frame. So that becomes very static, and then it’s almost like you could read through that series just reading the interior lines. Like, some readers might be tempted to skip through the outer lines the way you flip through a calendar. As though the action is happening in the interior.

Ratcliffe: In the middle … yeah. I find that too, myself.

Skinner: So is there a theatricality to it? The scene …

Ratcliffe: That’s a nice thought. The scene is like a static — the scene is this ongoing, recurrent, apparently repeating … but it’s not really. For several reasons. One, every day is a new day. Every time the sound of the wave is heard, the next day it’s not the same thing. It’s this ongoing investigation of space and time, of course. Of place, space/place. But over a period of ongoing time, one day after another after another. So it’s never the same sound, although the words are the same. There’s this kind of failure of language to enact those things. The words point to things that are occurring, which the words have in some way to do with, but those things have nothing to do with the words. And the words don’t discriminate between this sound and that, or between this color green and that color green. It’s using the same words over and over again, to point toward things that are constantly shifting and are not really being grasped by that language.

On the event

Skinner: In terms of events, or things shifting … in the days following March 11th, I knew I was coming to talk to you, so of course I looked for the tsunami in the poems on your blog. And I couldn’t find it. What’s the scope of event? How does event function in your work?

Ratcliffe: Well that’s curious. That’s a good question. You know, earlier on, in CLOUD / RIDGE, it would have been in there, the tsunami, because there was a greater attempt at, or a closer sense of actual events being transferred, with more particularity. The particular was registered in the poem more closely.

Skinner: And then the nuclear catastrophe …

Ratcliffe: Yes, CLOUD / RIDGE begins on July 2nd, so when you get to September 11th, and then September 12th: “blond woman calling on phone to ask man to give / short-haired girl her cell phone number, plane / exploding into World Trade Center in New York.” So this then takes over. Oona’s in New York, my daughter, giving me these eyewitness accounts. The events come in, really in a big way. So … the question is why aren’t they there now?

Skinner: Well, I did find the line, in the poem for this March 11th …

Ratcliffe: Was that the date of the tsunami?

Skinner: … that was the date of the tsunami, and you had this line, “method that remains the same.” I think it was either 3.11 or 3.12.

Ratcliffe: Of course, that line was probably transcribed, you know, “found,” and written in this notebook, before 3.11. I pay a lot of attention to these events (Japan, tsunami, Libya, too). But they’re not getting in, you know, as concrete references. In the interior lines I’m pleased if I find something that to me resonates with events.

Skinner: I was almost thinking: “ok, the method remains, the song remains the same.”

Ratcliffe: Well, you know, it’s curious. I post them on the blog. And this poet who’s done a lot of translation from the Japanese, Eric Selland, wrote the other day, with a comment about one of the poems, saying, “it’s really nice to find this ongoing continuity of things here in the face of these human and natural disasters that we are facing.” I also post my poems on Tom Clark’s blog, and sometimes Tom or his readers find something in my interior lines that resonates … you know. Tom’s pieces are so full of current events, I mean they’re really striking. He’s got all these images that he pulls — he really follows things closely. But they find things in my poems that resonate with current events.

Skinner: Now are they catching allusion, are they catching some source, or are they scrying or divining — trying to interpret some sign in the frame?

Ratcliffe: I’m not sure. It’s some particular detail of the lines that resonates with what the topic, what the concern is in that thing.

On Campion

Skinner: I did want to ask you about Campion, about beginning with Campion, and what that means to you now …

Ratcliffe: I remember Auden. Auden had a beautiful — he edited a Selected Songs of Thomas Campion, published by David Godine. Back in the early 1970s I found that book.

Skinner: Beautiful publisher — still going.

Ratcliffe: Yeah, he does beautiful work. Bill Berkson did a night last spring at Books and Bookshelves, you know: what about Auden, does Auden matter anymore? A lot of poets came. About maybe a dozen people came to read selections or talk a little bit on Auden, so I thought, well, I’d like to read something from that Auden selection of Campion which was really formative to me when I found it. It’s a beautiful book, and his essay was great, his little preface about Campion. He talked about Campion as a minor poet. You know, I think C.S. Lewis might have put that term “major and minor poet” in his book, English Literature in the Sixteenth Century. A “major” poet is Milton, or, of course, Shakespeare. A “minor” poet is Herrick, or Campion. Campion is praised as the greatest of the minor poets. It’s a matter of not taking on an epic subject — if you’re writing poems about love, or court ladies … Not so much CLOUD / RIDGE, because it’s full of political stuff and, you know, Picasso and François Gilot, Morton Feldman … But in this book the references are not identified, and they’re stripped from any sort of biographical loading.

Skinner: So what is it in Campion that you retain, at this point?

Ratcliffe: The way the language works.

Skinner: The measure? The number? Sound?

Ratcliffe: The measure … Yeah, all of that.

Skinner: There are two other questions that come out of Campion. One has to do with number, and one has to do with invisibility in the work.

On invisibility

Ratcliffe: Ah, that’s really important, actually. That could be a longer topic. Michael Cross articulated this a bit in a conversation we had. It was sort of in the back of my mind but he pounced on it. He wrote something about the Shakespeare, the offstage action, Reading the Unseen book — un-visibility, unseen, invisibility. I think that sometimes the ridge is invisible, if it’s covered with fog. I mean that word “invisible” shows up …

Skinner: That’s happened a lot this month.

Ratcliffe: Yeah, it happens a lot! So that’s one thing, but you know, in the notion of offstage action that’s talked about in words, it’s not seen. It’s invisible.

Skinner: Sound is not seen. Ronald Johnson calls sound the “invisible spire.”

Ratcliffe: Sound is not seen either. And the things that I see that I write down into the poems are not seen by the reader. They have to be imagined, if the reader can or wants to. Because the language in some way may appear to be generic: it just says “green,” you know. What kind of green? Oh, sunlit green. Well … there are all those different greens out there. It doesn’t discriminate. But there’s something about language making reference to or pointing toward or trying to bring to the page these things that don’t ever appear there except in the words. There’s this gap between the words and the thing.

Skinner: In the notion of listening to reading, I wonder if that includes Eigner’s sense — and this may be my idiosyncratic reading of Eigner — that there’s a way in which you can hear the world going on, as you read his poems. The poem itself as a frame for ambient attention. Listening to reading, in a dumbly literal sense, is like listening while reading, or listening to the experience of reading. And the poem is “ambient” in that it doesn’t capture your complete attention, it sort of allows you to listen while you’re reading.

Ratcliffe: I like that idea.

Skinner: Claude Royet-Journoud talked about this. You know his books with a couple of lines at the top of each page. He talked about enjoying the sounds that were happening while he writes and reads. It’s that blank page as the space where all the things can go on while the reader is thinking about those lines.

Ratcliffe: Absolutely. I find that when I get a chance to read pages at a time, ten pages, or twenty. That’s usually as long as you get to read. I think you hear some things, you follow, you drift off into your own thoughts, you pick it up again. It is like ambient noise. And there are these other noises going on.

Skinner: I know you use the phrase “listening to reading” in a somewhat different sense.

Ratcliffe: I have a class at Mills that I call Listening to Reading — and we spend a lot of time talking about the relations and differences between the poem on the page, as words, that you see with your eye, and the poem in the air, which is sounded when it’s read aloud, that you hear with your ear. Those are two vastly different experiences, but subtly different, and we don’t usually make a distinction between them.

Skinner: What about being … the other question coming out of Campion was number, being and number. I’d like to ask this rudimentary question: why for the first trilogy 474 pages, and why 1,000 for the second?

On number

Ratcliffe: Oh that’s simple, really. When I was writing Portraits & Repetition, it was getting quite long. [Laughs.] I’d written 100 page books before, works, projects. And then this was getting, oh this was really getting long, and what was going to happen? It really should stop. And then I went on a trip, I think I went to San Diego. And I thought, this would be a good time to stop. I like that number, 474, it has this sort of … it’s like 747, you know, the airplane.

Skinner: Symmetry.

Ratcliffe: Yeah, it has a certain numerological resonance.

Skinner: 4s and 7s.

Ratcliffe: So I stopped. And I actually didn’t start into doing REAL right away. About nine months went by, I think. And then I thought, gee, you know, I’d like to do another piece. Maybe I could do a trilogy of works that long. I’ll see if I can. So I started on REAL, and I aimed to get to 474. And then, you know, I was really into it. So I shifted and I did this one.

Skinner: CLOUD / RIDGE.

Ratcliffe: Yeah. And then I thought, ok, that’s the trilogy. But I don’t want to stop writing. I don’t know how to stop now.

Skinner: So you stopped and started again.

Ratcliffe: The next day.

Skinner: The next day!

Ratcliffe: Yes. As I say, after Portraits & Repetition, I stopped and I did other things. And then I started in again on these long things. So it’s been consecutive days ever since …

Skinner: It sounds like 474 in REAL is a “track mark,” basically, that you put in. As if you’re making a recording and you put in a track mark.

Ratcliffe: Yeah, except the form shifted from REAL to CLOUD / RIDGE.

Skinner: From one day to the next? You made a decision to shift the form?

Ratcliffe: Yeah. I invented a new form on the very next day.

Skinner: Had you been thinking about that before, or did you invent it on the spot?

Ratcliffe: I can’t remember. I’m not sure. You know, REAL is seventeen lines, five units. Portraits & Repetition also has five units, you know, five couplets. And it had five sentence structures. I think that this might also … [counting] 1, 2, 3, 4 … 5, 6, 7, 8 … 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16. No, it’s different. I don’t know. I invented this one. And likewise, when I went into Portraits & Repetition, I invented a new form. And in Remarks on Color. But at the end of Remarks on Color, I was in Paris. I didn’t have the wherewithal to invent a new form. And so I thought, well, I don’t need to invent a new form, I’ll just keep going. So Temporality continues with the same number of lines. It shrinks in length, it gets more compressed. And that was another thousand pages. Now it’s still the same number of lines, but I don’t have a new title for this work.

Skinner: So what about number? Is there buried numerology in your work, numeric pattern? Is there a counting meter?

Ratcliffe: You know, for years I wrote fourteen line poems, in various ways, sonnets. That’s another thing coming out of Renaissance studies. Campion didn’t write sonnets, but Shakespeare did, and so on. And they’re various … I mean even these poems in CLOUD / RIDGE are fourteen line poems, if you count the indented, you know, broken line as a single line, which I do. I think they’re fourteen line poems. But, no, it’s just habit. There’s not a numerological significance that I know of.

On document

Skinner: Is there a documentary impulse in your work?

Skinner: Is there a documentary impulse in your work?

Ratcliffe: I was going to say, thinking back to your question about the scene and the numbers, that there’s something about this work that wants to just mark the passage of time. Because I’m here, and I’m writing these poems from a very fixed … it’s kind of like Proust in his bedroom, you know; he goes inside, inside his mind. From what I understand about Proust.

Skinner: Marking the passage of what kind of time?

Ratcliffe: From one day to the next!

Skinner: I mean, are we talking absolute time, experienced time, durée, biological time?

Ratcliffe: Well, the ticking of the clock. You know, all of the above, because the poems are written at the same time, at daybreak. Bob was talking about these being like a prayer to the new day.

Skinner: To the dawn, yeah … saluting the sun.

Ratcliffe: I don’t think of it that way. But it’s a nice notion.