A conversation

Note: Jocelyn Saidenberg’s most recent poetry collection Kith & Kin (The Elephants, 2018) tracks the author’s yearlong attempt to surface those deemphasized aspects of language and living. What has been paraphrased, forgotten, or disappeared from the everyday returns in Saidenberg’s poetry, which mixes together the little deaths of houseplants with a politics of refusal (however fleeting) and an enduring grief for a friend. In particular, the account of Saidenberg’s Kith & Kin begins shortly before the death of Bay Area poet Beth Murray, whose posthumous collection Cancer Angel (Belladonna, 2015) won the California Book Award for Poetry in 2016. In “October,” Saidenberg writes of this loss, which inspires song, fracturing, and acceptance:

to shepherd her

across the waves in her

idea boat in a song

as her atmosphere of promise

an apostrophe to the future

I stumble into this where

atoms split I rescue

objects it’s my duty I

leave things as they are as

if to be summoned I remind

myself that she can’t[1]

One of a number of motifs that punctuate Kith & Kin, the owl suggests how this loss seeps into Saidenberg’s everyday life, becoming its own meaning-animal over the course of the year. In addition to a watercolor illustration of an owl by Alice Notley, the owl reappears severally in the months that follow: as an emblem and a prayer, as a refrain of whos. Through this repetition with a difference — an echo that is colored by the surfaces it strikes — the owl becomes a sign of new significance, part of the ecosystem of meanings that inform Saidenberg’s living. Like the common words proliferating in the private languages of Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons or Renee Gladman’s Ravicka novels, the owl is imbued with a peculiar intimacy, whereby the mutual construction of a shared language becomes the promise of a shared life. In Saidenberg’s case, this collaboration exceeds the community of the living, so that when the owl makes its final appearance, it is as a figure of collectivity, the living with the dead:

No more nobody or anybody, but bodies not the body a body

No more no one no thing any thing, for my plots are friends

with myriad bodies instead.

For instance a radius redoubled, but that’s not a figure.

See instead we are themselves, waves, no longer figured,

carried or held under but assemblies in unending seas

where shepherded by dolphins we are of them that are we &

that is what the owl knows.(60)

The “owl knows” that there is no “nobody” or “anybody,” only particular bodies, subjugated in particular ways, and it is a particular kind of violence (violence upon violence) to make abstractions of subjects and the means of their subjugation. Each body, each sign and turn of phrase, has its own fullness, even as that fullness is only partially recognized under the rubric of proper socialization or grammar. It is Saidenberg’s gift to be able to demonstrate how such fullness, while never completely communicable, may yet be suggested exactly through partiality and fragmentation.

In his review of Saidenberg’s Negativity (Atelos, 2006), Tyrone Williams writes that “[language] appears to have any number of positions in relation to the body. The struggle to locate language by triangulating the self, the self’s body and the other is hampered, first and foremost, by the ideology of carniphobia, the foundation of, among other irrational fears, xenophobia. It is not insignificant that those who have been most interested in the relationship between body and language are subalterns, those at the margin of, if not absolutely outside, normative sexual and gender determinations.” A variation on this “triangulation” can also be read in Saidenberg’s “June” from Kith & Kin, as a translator attempts to make sense of a departure:

Exeo but how? Ask her main verb?

Where is her main verb? When will I see her main verb at last?

What will her main verb hear today? Tomorrow?

Will her main verb walk in the streets in shadows? Will rain

be her main verb? (57)

The task of the translator requires that they be able to recognize “her” in language so that she may properly leave. But a departure demands a context, a direction, and an orientation. The disorientation that accompanies loss affords the translator some consolation — to see “her” again, not just in the terms of coming or going, but otherwise, in the weather. Just as the owl becomes insinuated in a private language of living, so too might the rain hold a special significance for the one willing to hold all the possibilities for translating “her” departure. As “June” concludes,

There are more than two types of people but there are

those people who divide people into types.

Usually two types.

As if only one leads & one follows.

As if only one is & one isn’t.

But bodies already protest.

A walking refusal instead side by side with the dead. (57)

Saidenberg’s earlier books, such as Negativity and CUSP (Kelsey St. Press, 2001), have stressed the potential of gender and sexuality to negate those forces that have maintained a violent status quo. Saidenberg’s recent work has built on those imperatives by meditating on the boundary between the living and the not-living, variously speaking, as in the case of personal loss in Kith & Kin, or as in the case of Bartleby the Scrivener, whose story animates Saidenberg’s Dead Letter (Roof, 2014). Saidenberg’s Kith & Kin asks us to consider the limits of our relationships — with the living, the less than living, and those living otherwise — as well as the standards by which we recognize life and what sustains it.

Jocelyn Saidenberg has been an essential architect of and contributor to the San Francisco Bay Area’s overlapping innovative literary and queer artistic scenes for more than twenty years. Saidenberg’s poetry fits alongside that of her contemporaries (including kari edwards and Rob Halpern) and her mentors (including Myung Mi Kim and Robert Glück), writers who have developed strategies for politicizing fragmentation and hybridity and for producing pleasures through syntactical bravado and the allure of scandal. From 1999 to 2001, she was the director of Small Press Traffic, and for ten years she was one of the curators of Right Window Gallery.

Her poetry collections have been published by several iconic Bay Area small presses, and in 1998 she founded Krupskaya, which has been publishing some of the most exciting experimental poetry and prose through its collective editorial practice. Krupskaya was how I first became familiar with the name Jocelyn Saidenberg, ordering titles from Small Press Distribution and then adding them to my extracurricular reading list as a graduate student at UC Davis: Kevin Killian’s Argento Series, Renee Gladman’s The Activist, and Stephanie Young’s Ursula, or University. Recent Krupskaya books —including Lauren Levin’s The Braid, Wendy Trevino’s narrative, and Samantha Giles’s Total Recall — are dedicated to the rage and imagination required, as a minimum, for the kind of social transformation many of us are relying upon to survive this twenty-first century. To have my first book added to such a roster was unthinkable to me when I was a fledgling poet, though I was lucky to have my book Snail Poems published by Krupskaya in 2016. Since then, I have witnessed Saidenberg support and enthuse about many younger writers, so that her gestures of welcome may now feel like the ideal of the Bay Area poetry scene.

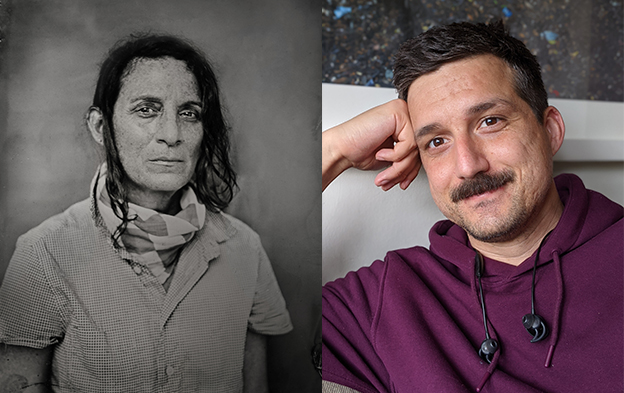

In August of 2017, we sat down at her dinner table for two hour-long conversations. The conversations we shared, which form the core of the interview that follows, were a sprawling oral history that gave me the opportunity to ask her about her five previously published books of poetry as well as her education in community-building and the Bay Area poetry scene. In the years that have followed, our friendship has only continued to grow. It has been my pleasure to learn more about her development as a writer, as it is my pleasure to present this interview to you today.— Eric Sneathen

Eric Sneathen: Kith & Kin seems to be a journal of sorts spanning a year in the life of the author, with a poem to represent each week of the year, approximately. In the Notes that follow the poems of Kith & Kin, you write that the book “is born of a desire to write what [you] tend to deny or avoid” (67). What can you say about the process of writing this book?

Jocelyn Saidenberg: My initial intention was to create a prohibition; I needed to stop writing what I had been writing for the past three years and to start writing something else. I had a strong attachment to the book I had completed, Dead Letter. There I had written from within someone else’s subjectivity, and while that subjectivity was one that in no way invited me in, I, nonetheless, side by side and day by day, found and failed to find ways to live through and with Melville’s Bartleby, to give an account of his unaccountable life with our own language. So how to leave that shelter? I thought best to create another so unlike and yet equally difficult, that is, my own self. On the first day of September, I started to write each day in a notebook by hand. I assigned each day a specific designation, a prompt, save Sunday, the day I reserved for composing. For instance, the Monday prompt, Organ Recital, was my repeated point of departure. That’s a reference to a familiar phrase I’d heard my grandparents use when they’d report the status of their various bodily organs: my eyesight is worsening, my lower back aches, my liver feels toxic, my heart is broken, etc. While each day had its specific prompt, the writing inevitably would exceed the designation through an associative process that would lead me in diverse and unanticipated directions: dreams, problems I was working through, the everydayness of my life, fictions of my self, parts of language and broken phrases, birds, dogs, cats, moons, weather, and so on. So each morning, in pen in my notebook, deferring the inevitability of screens and devices (work, obligations, “real life?”), under conditions of my own devising, I’d write about things I tended not to want to look at or acknowledge — my aging body, my organizational obsessions and messes, the banality of my everyday — in part to gain access to what I had excluded. But I also had a hunch that if I got as close as possible to myself, I would find myself in proximity to others who are also me, ones who mumble, who yell in rage, who are dead, who dream me at night, who are lost to me, whose beings my being is composed of.

Sneathen: The poems of Kith & Kin feel fragmented yet intimate, like there’s a kind of coded language being sung with great affection and care. Opening to the final “January” poem, I read:

missing tether

lost for capture

receptive for weather

for two cats overheated

that’s block for deficit for

raining for cleaving

& I still need help with

everything

I can’t

defend myself from myself (38)

In the image of the cats, I see the kind of daily life that you mention in your notes. But I also sense a great loss and a language puzzle, too — the “missing tether” that might bind together a list of things “for” one another, when “for” might suggest alliance or equivalence. Can you tell me more about this poem?

Saidenberg: I’m not sure what else to add to your beautiful and generous engagement with these lines other than it affirms for me that I write for you, my friends, the people I read and write with, who together, differently, compose and tend to our forms of living and relating.

Sneathen: I’m interested in how you compose your poems. Can you say more about your Sundays of turning your notes from the week into the poems of Kith & Kin?

Saidenberg: It’s hard to recall, not because time has passed, but because I don’t know how to describe a process that for one thing changed every Sunday and for another when I am in it, I’m not tracking myself being there, but rather just that, being there with the sounds of language, moving the poems in and out shapes, listening for the rhythms of correspondences. One element that was particularly exciting for me then was to learn all the many capacities of lines and line breaks. These discoveries were thrilling to my ears especially. (Sentences had become for me a more familiar duration for composition.) After the year of Sundays, I revised the whole, on several occasions, with the help of incredibly generous readers and friends, and later in conversation with the two editors of The Elephants, Broc and Jordan, who were so insightful, encouraging, and engaged.

Sneathen: You conclude your book with the statement that “Who we are is never fully knowable, for we constitute an assembly of others and selves. In this sense, the writing summons and is summoned by others collectively, enigmatically as our elaboration of losses and assemblies” (67). Can you please say more about what you mean here?

Saidenberg: Today reading these concluding lines, I am disturbed by my use of the pronoun “we” and what it might assume, recognizing that what I meant by it was not universal but a proximate and imaginary assembly of bodily and psychic vulnerabilities. But since I completed that book, I am continually learning the many ways that we are and are not mutually vulnerable or exposed, and how those differences without exception precipitate ethical and political conditions, material and otherwise, that must acknowledge the systemic abandonment of the most vulnerable communities.

Sneathen: You, your name, your books, and your press have always been a part of my experience of the Bay Area writing scene. Even before we became friends, I began collecting your books from the used poetry sections of Moe’s and Green Apple. I’m curious, what brought you to San Francisco?

Saidenberg: I came to study poetry, to get an MFA at SF State. Before moving here, I was living in New York, where I grew up, and I was in Bernadette Mayer’s home workshop. At that time, she lived a few blocks from me in the East Village. Maybe three nights a week, I would also go to the Poetry Project at St. Marks to get an education in the kind of poetry that I was interested in. On one of these nights, I heard Myung Mi Kim read from her book Under Flag, which had just come out. I knew I wanted to go study with this person, so I applied. Actually, I applied to two programs — Brown and SF State. I think I ended my personal statement with, “So, what do you think?” [Laughter.] I couldn’t quite commit to applying to MFA programs and what that meant. I was very much in the thrall of Bernadette, who had Plato write her blurbs, for example, and whose relationship to anything institutional was … skeptical. She’d say to me, I’ll submit your poems to journals under my name, with the idea that that’s how ridiculous it is. Not that my poems were ridiculous or that her poems were ridiculous, rather the whole institutional system.

Sneathen: Did you ever do that?

Saidenberg: No. No. I wish I had. Ultimately, I didn’t get into Brown, and I did make it into SF State. I didn’t know anybody in the Bay Area except for a childhood friend writing a dissertation with Kaja Silverman at Berkeley. He used to be a bookie, and we used to go to the Aqueduct racetrack together, near JFK airport, and I’d bring my passport and my lucky rubber band — this was when I was in high school. My hope was that I would win a trifecta, and I could just fly away and never return, but that never happened. I had to get back on the F train and go home.

Sneathen: Do you still bet the horses?

Saidenberg: I used to like betting on horses, but I haven’t done it in a long time. I’m actually really good at it. I have a system.

Sneathen: Do you go down to the paddock and look at the horses?

Saidenberg: No. My system for horse-betting is not based on looks. I remember one time going to Santa Anita in Pasadena. It was New Year’s Day, and we all dressed up. I won piles of money, so I went out and bought this outrageously expensive pair of sunglasses that I then broke when I fell from my motorcycle. Of course, I don’t endorse what they do to the horses, and even back then I intensely identified with animals, but I guess my betting compulsion overrode my care for others. I also thought that the jockeys were kinda hot.

Sneathen: Because they’re so small?

Saidenberg: Yeah, they’re the little men I wanted to be.

Sneathen: I’m curious to hear more about Bernadette’s home workshops. I didn’t realize that you had done those.

Saidenberg: Yes, they were amazing. I had a friend who was at the MFA program at Brown, and he had just met Bernadette. He called me, saying, You need to meet this person. I think she lives really close to you. You should call her. And I was like — I’m shy beyond belief — how am I going to do this? But I called her. At that point, Bernadette was an inveterate phone person. This was 1992, and we talked on the phone for hours.

Sneathen: The very first time?

Saidenberg: The very first time. And then she invited me to come over, and I met her kids, who were living there, and then she invited me into her home workshop. Bernadette would say, You go home and you write your poems. That’s great. But what we do here is experiment. It really was like that famous handout of hers, including plenty of collaborations — sitting at her dining room table, really crowded in, this big piano behind us and lots of books. I felt an incredible discomfort with everything and excitement. I was thirty. I’d been reading a lot of poetry, and I’d done other kinds of writing. But I wouldn’t say that I’d committed myself to writing until that moment, and I feel so grateful that it was with her. I needed to be exposed to different ways of writing. It wasn’t like I didn’t have anything to say, I had plenty, but I needed to find ways of saying it, because the “it” is embedded in the ways of saying. I was not interested in the lyric poem that had a stable “I” with the tidy ending filled with revelation. That didn’t match my experience. You know, in some ways I didn’t know how to be in the world, so I was looking for ways of being, which led me to looking for ways of writing. That’s what being in Bernadette’s workshop offered to me: how to be and how to write in the world.

Sneathen: I’m struck by how you’re looking for something adequate to questions of being and writing. It’s a demand that strikes you, immediately, on the threshold of poetry and a poet’s life. Bernadette offers you this invitation to seek out an adequacy in language, so warmly it seems. And it’s interesting to think about your work as an amalgamation of influences. Bernadette’s work seems so opposite from yours in many ways. Her work collects all these details and then gushes with this charming, hypnotic verbosity; while I think of your work, generally, as so concise and driven by your crafting, with great care, something precise. I love coming upon those moments in your poetry when this kind of precision also carries with it ambiguity and open-endedness.

Saidenberg: Well, what you get from your mentor, your teacher, it’s enigmatic. We did share a love for Latin poetry and hijinx. In rereading my early books in preparation for our conversation, I thought, Oh my god, if only I had been more concise. [Laughter.] They feel like there’s this extra — not extra, per se, it’s not quantity but an overcrowding — like there’s no room to breathe in them. I wish I’d been exploring the composition on the page in more capacious, responsive ways.

Sneathen: In the email I sent to you I suggested that we might think about what is impossible to say with language, the limits on what might be sayable. I read this growing interest in your work in language’s gestural quality — how it reaches toward meanings that can’t actually be achieved, how language props up meaningfulness, even as it habitually fails to make contact with meaning.

Saidenberg: So how is meaning made or unmade, and where might it live? I think of meaning-making in relation to a kind of symptom that indexes possible meanings that both eludes language and also inhabits language. What preoccupies me is to find out what language can do, what kind of worlds it can create that I could live in and that others might be able to live in. I’m not writing about the limits of language or about what’s unwritable, but rather wanting to render in writing being in that experience of language. Sometimes I write illegibly I suppose, but that’s when you’re experiencing my failures, my blind spots. While moving toward a horizon or limit that resists me, I’m trying to outline at least its shadows and echoes. I’m not interested in merely reiterating or performing what language can’t do. It’s what I often admire in other poets, watching them push against the limits and boundaries of language, the rules of grammar, working in and with the disordering of language.

Sneathen: I’d love to hear more about your time studying at SF State, including your time with your new mentors.

Saidenberg: Working with Bob [Glück] and Myung Mi Kim simultaneously was magical. Both are incredibly generous readers, and they often would make recommendations for what I might want to read or research in relation to whatever project I was working on. I also took a class with Aaron Shurin, and I was his teaching assistant. Aaron was a delight to work with, always wickedly funny and smart and inspiring.

Sneathen: Would you be willing to spin some New Narrative yarn for me? What were Bob’s workshops like? Who was there? Did writing from those workshops make it into your books?

Saidenberg: Bob’s home workshop. There was always something amazing to eat and then we sat in his living room and discussed and read each other’s work. I met Rob Halpern and Robin Tremblay-McGaw there. I was a little intimidated by the other participants and remember taking furious notes and not saying much. Rob and I became close friends then and would meet regularly outside of the workshop and read together. I remember, for example, reading over and over John Donne’s “The Funeral” at the Café Flor in a rapturous state. I also remember during that time going to Bob’s house for a reading by Bruce Benderson. This was when Small Press Traffic didn’t have a physical space, after losing the bookstore on 24th and Guerrero. Rob and I shared a house for a while, and at some point, Earl Jackson and his hairless cat Gus also lived with us. I found it hard to warm up to the cat but loved living with Earl. He always had great movies to recommend, although some were far too scary for my taste.

Sneathen: And what was it like for you to transition out of the MFA program?

Saidenberg: I taught composition at State after I graduated, and I dedicated the early hours of each day to writing. Maybe the hardest part, which still is, was showing up for writing every day, finding space and time for composing while needing to go to work each day or having conflicting priorities.

Sneathen: I appreciate how a question about your poetry becomes a commentary about community that leads back to writing. Your writing practice feels so social, communal even. I remember talking to you about Negativity, one of my favorite books from Lyn Hejinian and Travis Ortiz’s iconic Atelos series, and you said that you wanted, through your book, to bring as many people as you could into that series by way of collaboration. The dedications throughout that book also speak to your sense of writing as a collective practice, and your collaboration with Bob, “In This Country,” is a treat. Here’s a sample:

That country daydream this country nightdream. That country’s name is

holes and buzzing power lines.

In that country a cock gushes sperm while seeking a long-term

relationship, walks on the beach, travel, moonlight, Italy. In that country,

crzyfrmtheheat —

In this country: disquiet. In that country: the past’s baneful presence in the

new experience. What makes us known to each other through tears, that final breath. In that country we are standing together as cars pass; we anticipate tearing into each other in an embrace mistaken for desire. In this country — it is not — is just that shiver we wake to each day.

In that country the truth does not include you, your memory a rotting rag

does not support the present.[2]

Can you say more about your collaboration?

Saidenberg: Bob and I wrote this piece as a narration for a short silent film after we saw a Benshi performance at the PFA. We wanted to explore the possibilities of narrating pornographic visual material without describing it in any direct or explicit way. We used the refrains, “in this country” and “in that country,” to create a rhythm while dislocating it temporally. We sent it back and forth and each added a line or two.

Sneathen: In her blurb for your next book, Dead Letter, Lyn Hejinian writes, “This is a tale of Wall Street, and readers will be reminded of the recent occupation there. But, more fundamentally, this is a tale of the Other as autonomous, exercising a refusal to be used even as an object of interpretation, and requiring the right to love.” Though I imagine you would think all of your books are in some ways “political,” this book seems the most explicitly so, given how Lyn, and Christian Nagler in his afterword to the book, link it to Occupy. I’m curious what changed for you? And how do you relate to the notion of political writing? What does this have to do with the encounter with the Other?

Saidenberg: To render an encounter with the Other is a form of ethics, a politics. I don’t know how to respond to what, at times, seems like a mandate to write in direct relation to our political moment. I need to approach it through indirection, to allow the passive, the shadows, the enigmatic, the limp, to find a way in.

Sneathen: To bring it back to writing and inquiry, I’m curious about how you would describe Dead Letter’s relationship to Herman Melville’s story. Earlier I used the word remembering, but I’m not sure if that’s quite right. It’s hard to know which word to choose: remembering, representation, reconsideration? Renee Gladman calls it a retelling.

Saidenberg: Maybe, a failed habitation or hallucination! That is, a performance of my desire to inhabit Bartleby’s position, to dwell within a subjectivity characterized by a persistent resistance to being recognized, and a refusal of any form of recuperation. So my version, this writing-through of Melville’s story, stages the narrative of its failures and ecstasies while acting as a witness to another’s immobility, negation of desire, and transformation.

Sneathen: I’m reminded also of the motif of the shipwreck, which is sustained most obviously in your chapbook, Shipwreck, but also recurs throughout your poetry. My mind goes to George Oppen, his “shipwreck of the singular,” but —

Saidenberg: This image of being at sea, of being adrift, where there is no safety, no security of a shore, replete with peril. It’s a figure that always accompanies me.

Sneathen: I hope one day Shipwreck, which was published by Margaret Tedesco’s wonderful limited-edition press [ 2nd floor projects ], will one day be collected into a book. For now, I want to read these lines, because I simply love them:

I am trying to meet a wave, a thread of sail, but fear we are

ourselves one of them on which we fall.

In what we see, love, I rub my eyes, repeatedly, tear up.

Little shipwrecked there, horizon’s evershores.

Embark heart there, little ship, love’s light called by wind.

Love strange little ship there however dim, love, however.

Pair what’s yours, seed what’s not.

How frail our ship our waves how dear ought to be to carry us on.

Your waves, ours, love, revising themselves, repeatedly.[3]

Saidenberg: If we know that we’re always already in that state of shipwreck — that in itself is possibility. To not have the illusion that there is something otherwise. That seems hopeful. I’ve been thinking a lot about illusions and disillusionment. In part because I was thinking about your questions about community. And I had this thought: when you believe in something and you share that belief with others, that is the grounds for the possibility of making community with others. You don’t know it’s an illusion, though, until you become disillusioned. But you have to have that illusion. It’s a necessary fiction in order for you to make things possible. So the disillusionment is just as important as the illusion. Because you can see that the promise, the wish, the collective desire, was actualized. Still, there’s such a negative valence to both illusion and disillusion. The bitter taste of being disillusioned. But, no, if you didn’t have the disillusionment, you wouldn’t have the illusions. The illusionment? And they’re both really necessary.

1. Jocelyn Saidenberg, Kith & Kin (Vancouver: The Elephants, 2018), 13.

2. Jocelyn Saidenberg, Negativity (Berkeley, CA: Atelos, 2006), 51–52.

3. Jocelyn Saidenberg, Shipwreck (San Francisco: [ 2nd floor projects ], 2012), 7.