Al Filreis

Al Filreis

Dorothea Lasky: What is between us

Notes on her recent work

January 21, 2020

Introduction to Almallah's 'Bitter English'

October 16, 2019

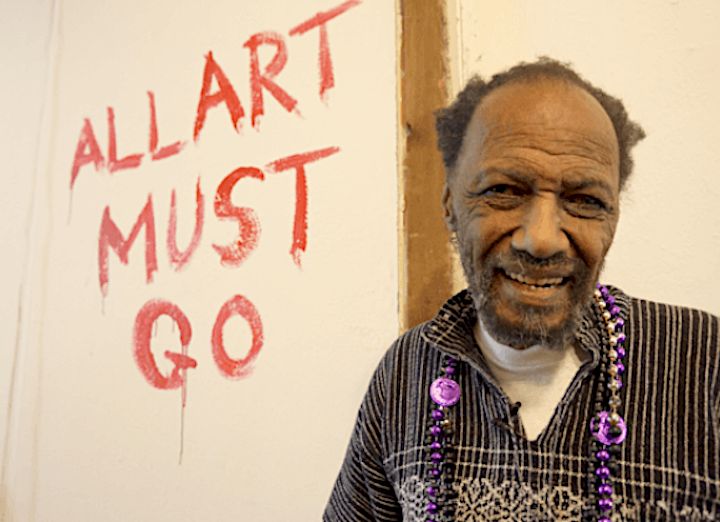

Steve Cannon: New Orleanian, Black Bohemian, Art World Giant

by Tracie Morris

July 16, 2019

Samuel R. Delany: disability and 'Dhalgren'

June 6, 2019