It was a place I might have dreamed if it hadn’t been real, this building slated for demolition located in a country far from home. The former site of an art college, the structure itself no longer stands, but one June evening in the early years of the twenty-first century, it hosted a party for the ages.

Each classroom transformed into an all-night gallery, filled with art by generations of students who had learned there how to see, how to listen, how to make. Studio after studio of imagination translated into reality. Outside, on the lawn: wine, feasting, revelry. The sharing of decades of memory. If you look closely, you can see gargoyles keeping watch over the festivities.

At some point during the celebration, I found myself inside a large room, empty, darkened. On one wall, a pull-down screen held taut with string. On a lone table, a Super 8 projector affixed with a sign I couldn't yet read:

Pour voir le video, faîtes du bruit. Merci.

The words were thanking me for something, but I didn't know what. I circled the table, on the verge of potential. I stared at the screen, quizzed the projector. The room remained dark. I petitioned the sign. The words remained silent. Reluctant to give up completely, I copied the phrase into my notebook and returned to the central hall, raucous with a language I didn't yet speak.

Suddenly, the music started, everyone dancing, and language didn't matter for hours.

Later the same evening, maybe somewhere toward morning, I ventured back into that curious still- life, this time with friends who might ignite a spark. They regarded the projector. They glanced at the sign.Then, as if interpreting an ancient spell, they began clapping their hands, stamping their feet, calling out, making all kinds of racket. The projector yielded its secret:

[video:https://vimeo.com/23041634]

The invention of French artist Christophe Écobichon, "Orchestré" sets into motion a relationship between viewer(s) and conductor predicated on interaction. As Écobichon explains of the device's mechanics: The film appears only if one makes noise. The conductor then impels you to continue, and in this way contributes to his own existence.

If the loop plays with our notion of who is doing the orchestrating, it also invites us to consider what is being orchestrated. One straightforward interpretation: the creation of sound. In the beginning was the Word. Which might be to say: the creation of all things. With regard to translation, straightforward often arrives as illusion. Or maybe a trick of the light, one of the first creations.

Sometimes words escape not only translation, but also the casing of their original language. Relaying a response by Joan of Arc to her prosecutors, Anne Carson provides an example that evades straightforward altogether, "falls silent . . . does not intend to be translatable . . . a sentence that stops itself":

The light comes in the name of the voice (in nomine vocis venit claritas).

The film appears only if one makes noise. Which might be to say, the name of the voice orchestrates both sound and light, the whole darned movie. Which might also be to say, Sentences that stop themselves are the very ones that animate.

Whether words fall silent through translation or incomprehension, illusion or incantation, strangeness in language is one way sentences both stop and propel us into motion. We sleep in language, writes Robert Kelly. We sleep in language, if language does not come to wake us with its strangeness.

Down the street from my house in a city friendly to strangeness, the Museum of Jurassic Technology houses another orchestration animated, if not by voice, then by presence. The Bell Wheel is a musical creation inspired by the design of 17th century Jesuit scholar Athanaseus Kircher (1602-1680).

To make the instrument rotate into sound, one must stop inside the room where it hangs, suspended from the ceiling:

[video:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mtswcgC14Yw#action=share]

The Bell Wheel's mechanisms draw from Kircher's Musurgia Universalis, (1650) "an exhaustive compendium of musical knowledge" which discusses, among other things, "the Boethian concept of the musical harmonies' mathematical correspondences within the body, the heavens, and the natural world, and concludes with a discussion of the unheard music of the nine angelic choirs and the Holy Trinity."

Peter Apian, Cosmographia, Antwerp, 1524

Such a model of the universe, based on Ptolemy's geocentric system of nested spheres, depended upon the outermost (and swiftest) sphere for its celestial music. The Primum Mobile, or first moved, was believed to cause the movement of all the spheres within it, setting the whole of the cosmos — and its music, silent to human ears — into motion.

As far as the Music of the Spheres is concerned, what was orchestrated was known, if not exactly heard. Who did the orchestrating was also unquestioned — for the medievals, it was God. But what impeled the movement in the first place? Which is to say, how does a prime mover move things? C.S. Lewis offers Aristotle's response:

κινεϊ ώςέώμενον ,"He moves as beloved." He moves other things, that is, as an object of desire moves those who desire it. The Primum Mobile is moved by its love for God, and, being moved, communicates motion to the rest of the universe.

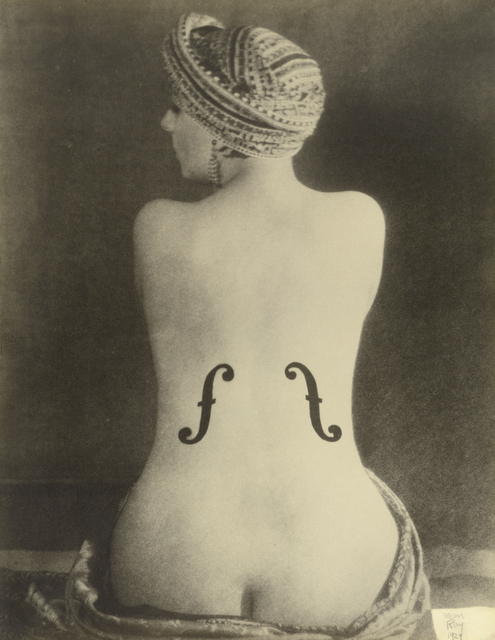

Orchestration set into motion through translation of desire. Maybe for God, maybe for beauty, maybe for the music itself, twin F's sounding the curves of a woman's back. How do you translate silence? asks Mira Rosenthal, as she translates an animated version of Man Ray's surrealist photograph in this poem by Tomasz Różycki, originally written in Polish:

Landing

Let's land, let's land already. Dawn breaks, buildings

slowly unfold below, the clouds disperse,

a chill skims open space. We've had enough

circling, watching for earth, dull days stretched wide

as open sea, battling wind and sunny delusions,

flaring white flags in a dream. They're saying that

the fuel's almost gone. Our stewardess is Kiki.

Drawn on her back, two F's gush vodka, no,

music. Vodka. Let's land. The city's warmth awaits,

shopping to do at the hub of the world

where we'll get lost some Saturday, our basket full

of cake, eggs, lamb. The children wait. We promised

the story's end, but time is paramount. The wolf,

tanked up on grandma and the fridge's feast, now sleeps.

As Rosenthal notes, the Kiki here is Kiki of Montparnasse (Alice Prin), who appears in Man Ray's "Violin d'Ingres" in a pose translated from the bathers of French neo-classical painter, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867). One plays a stringed instrument.

Ingres' La Baigneuse Valpinçon, 1808, & Le Bain Turc, 1862, Louvre, Paris.

Strange the way things turn out. Ingres thought he might earn renown for his expertise as a violinist, but it was through his elongated nudes, silent. A violin d'Ingres emerged as a French colloquialism, meaning a secondary skill by which a person is known, a hobby or pastime. The iconic photograph plays with these ideas, suggesting, among other things, Prin's armless body as a plaything of Man Ray's. But maybe it's the maker who's being played. A photograph depends upon light for its creation, but it also stops time, so that image might forever be animated by imagination. Whatever, or whoever, sounds the name of the voice, orchestration itself depends upon an entire universe of response — stopping, looking, translating music from silence. The way dreams are set into motion by sleep, the way strangeness can wake us into life.

Maybe we don't translate silence so much as organize it, the way a culture organized its universe into a cosmology that created a music so ethereal, we're still learning to hear it. As Ilya Kaminsky proposes:

We learn something new about the English language each time we confront another syntax, another grammar, another musical way of organizing silences in the mouth. By translating, we learn how the limits of our English-speaking minds can be stretched to accommodate the foreign, and how thereby we are able to make our own language more beautiful — to awaken it.

•

A Conversation with Mira Rosenthal

How did you come to translate the poetry of Tomasz Różycki?

I came to translation by accident and thanks to other translators. It’s not like I set out to translate Polish poetry. Rather, Polish poetry translated me. It estranged me from my own tradition and sensibilities just enough in English versions done by some amazing translators—Czesław Miłosz, Robert Hass, Clare Cavanagh, to name a few—that I wanted to understand what that revelatory experience might be like in the original language. And I was harebrained enough to set about learning Polish in my late twenties. One thing led to another. I found myself living in Krakow on a Fulbright Fellowship, ostensibly to write what would become my first book but also to see what the younger generation of Polish poets was up to. Różycki’s book Twelve Stations received a major prize that year. I began reading his work and jotting down the crisscrossing that was going on in my fledgling English-Polish head, eventually working through my questions with a native speaker. Without really realizing it, I was translating.

Where are some places you've wandered/traveled/voyaged, either in the real or in your imagination? How does location inform your process?

I work best at the farthest remove from my own culture’s chatter, especially that of the poetry biz. This happens abroad, though it also comes into play at artist residencies and the like. Yet I don’t think of myself as expat material. Rather, I find being at the greatest remove from America allows me to see it more fully and understand my relationship to my homeland in all its complication. That is, I feel even more American. Finding myself a bit adrift and unconnected to the foreign culture outside my door also makes it easier to call “home” any room and desk where I sit to write. Writing becomes my native land. When I’m in America, I get sidetracked more easily by the blather. When I’m abroad, I’m able to settle more fully into the realm of writing.

Might you share an experience of/encounter with strangeness/wonder/unfamiliarity?

My first real trip to another country was to India. My mother spent half of her childhood there, and my grandfather was born and raised there because his parents went over as missionaries with the Church of the Brethren. I grew up with Indian culture, a Hindi name, and eastern religion—like many good children of missionaries, my mother ended up adopting one of the belief systems of the subcontinent. My Jewish father was right there with her: this was the 1970s, after all. There’s even a name for my family’s mix of ideas and traditions: the Hinjew. Stepping off the plane in New Delhi was a hyper-embodied experience for me. Here I was in a completely foreign city, but so many of the gestures and sounds and smells and colors felt utterly familiar. Yet I didn’t speak the language, and I could never blend in. I had no idea where home was, except in the senses, in the body.

Is there a language you're drawn to, would like to know?

I’ve been thinking less about specific languages and more about the silence that surrounds language — any language. This comes out of my teaching poetry writing and trying to contend with the difficulty of having a conversation not only about craft but also about mystery. What makes us feel like a poem is the exact, right vehicle for a specific emotional intelligence that cannot be expressed in any other way? How does a poem fill us with mystery and that kind of understanding that goes beyond words? And, by extension, what happens when we change the language, change the vehicle, through translation?

My suspicion is that poetry is less about language and more about the silence that language gives shape to. This might have something to do with Emily Dickinson’s “slants.” Certainly there is white space, the presence of what is purposefully left unsaid. But there are also the extra units of meaning, built through lineation, that pull against syntax. These coalesce and hover around the poem — another element that is both spoken and, at the same time, not spoken. They are created with the line unit and then dissolved again with the resolution of the next line. It’s difficult to describe this aspect of poetry. Ilya Kaminsky, a poet quite familiar with living in translation, speaks eloquently about it in some of his commentary.

How, then, does all of this function in translation? How do you translate silence?

•

Mira Rosenthal is the author of the prize winning collection The Local World. Among her awards are fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the PEN American Center, and the MacDowell Colony. Her translation from the Polish of Tomasz Różycki’s Colonies won the Northern California Book Award and was shortlisted for several other prizes, including the prestigious Griffin Poetry Prize. Her poems, translations, and essays have been published in many literary journals and anthologies, including Ploughshares, American Poetry Review, Harvard Review, and A Public Space. A former Wallace Stegner Fellow in poetry at Stanford University, Mira will be Assistant Professor of poetry Writing at Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo, starting in the fall of 2016.

Tomasz Różycki has published six books of poetry, including Colonies, The Forgotten Keys, and the book-length poem “Twelve Stations,” winner of the Koscielski Prize. He has been nominated twice for the Nike Prize, Poland’s most important literary award. He lives in his hometown, Opole, with his wife and two children.

•

Notes:

Anne Carson, "Variations on the Right to Remain Silent," Nay Rather (London: Sylph Editions, 2013), 4, 10.

Christophe Échobichon, "Orchestré," exhhibited at L'École supérieure des beaux-arts, Tours, France, June 2013.

Ilya Kaminski, The Ecco Anthology of International Poetry, edited with Susan Harris of Words Without Borders (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2010), xl. Robert Kelly quoted, xlvi.

C.S. Lewis, The Discarded Image (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1964), 113.

Man Ray, "Le Violon d'Ingres," 1924, gelatin silver print, 29.6 x 22.7 cm. Image used with kind permission from the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California. Copyright © Man Ray Trust ARS-ADAGP.

The Museum of Jurassic Technology, "The World Is Bound With Secret Knots: The Life and Works of Athanasius Kircher," Los Angeles, California.

Tomasz Różycki, "Landing," Colonies, trans. Mira Rosenthal (Brookline, MA: Zephyr Press, 2013), 69.

A poetics of the étrangère