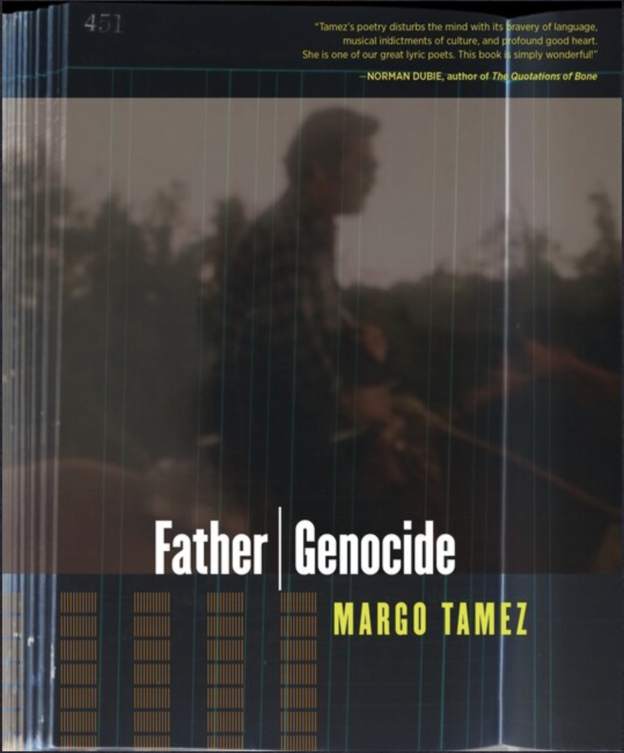

Reading Margo Tamez's "Father | Genocide"

Margo Tamez’s Father | Genocide was published by Turtle Point Press in 2021. A book of Ndé Dene [Lipan Apache] ‘place, memory, and poetics,’ Tamez describes currently living “on unceded sqilxw lands on the Okanagan Indian Band Reserve #1 (near Vernon, BC) as an invited guest.”

We are on opposite nodes of an entire continent, and I knew nothing of the smoke.

The fire’s widening container a made architecture of disappearance.

Before the interview, Margo Tamez emails:

I will not be online

I will be putting some lines

of protection, cutting back

tall dry brush and starting sprinklers

along those facing edges

I write back:

I completely understand.

I delete it.

Complete is fill up, finish, and floating in the sometimes-hazy skies of eastern shores I could not finish anything about the tall dry bush,

could not identify any perimeter,

could not face an edge.

On the desk is Schiller’s Crossed Wires on the imperial trajectories of US telecommunications networks. Speaking to the imperial trajectories of US spark and flame, of US ash fly.

Perhaps the essay could obviate the very (infra)structures that enticed

the possibility of a communication

and those structures which blew out the same.

I could write with open spaces

that are themselves the disapp (earance, ointment), dissipation in

communications under such structures.

“Texas is an open-air detention-hall.”

...

“He said, ‘Our condition

in Texas is a silo. Texas

is a storage structure.’”

As a work of memory’s inheritance

post-memory

on Ndé Dene land

Father | Genocide is demarcated by a litany of posts

which are mutually implicated.

“Only way I

can hold memory is remember the # of posts”

The valences of post are intertwined:

penitentiary posts

bollard posts

steel posts

lamp posts

post memory

barbed wire posts

digital hearsay posts

post as mail

post-survivor.

This documentary approach to a keyword study in poetry works towards making audible the remnant iterations of state violence embedded in language.

The post in colonial Texas a project of military occupation, settlement enticement, territorial legibility, land privatization, food source extinction, movement constriction.

“Your unanswered letters spiral about me.

My responses left unsent.

You passed before I went to the post.”

Through incorporating primary source material in a documentary mode, such as Maria von Blücher's Corpus Christi: letters from the South Texas frontier, 1849-1879, this poetics interrogates what is underneath settler statements. Rodney Carter's “Of Things Said and Unsaid: Power, Archival Silences, and Power in Silence” is translated into poetry iteratively throughout the book.

Tamez engages poetic form and visual design to read historiographies of settler colonization differently, in a series of conceptual translations of particular words, primary sources and secondary sources. Through digital warping and graphic distortion, the reader looks on words from behind or from the horizon-line of the page, upending what has been assumed as front and gazing at words longitudinally.

Form becomes investigative and a means of reading.

“You waited in the waiting room the waiting room is an archive.”

“If stripping and illegalizing Lipan-Comanche inter-marital kinship language was

the first wall

the waiting room

is where we are conditioned

to practice disciplined

submission to penitentiary soul strip.”

This poetry addresses nested scales of waiting by design of the settler state: the waiting room is both site and state structure. Verse works with spacing and line break to grapple the wait, to compile and compare scopes of waiting in relation to the state that pit into complicity the momentary and the long-enduring. The space of the page becomes an area to address spaces of containment.

In the face of the waiting room, Tamez names this poetics ‘timebending’ through “‘Indigenous fusionism-Indigenous futurism’ — a union of pastpresent, bodyknowing, intertext, bent tradition, landguage, and familial blood-knowing.”

The epistolary second person creates an intimacy, against the exposures of both settler colonial violence and conventional academic mode, navigating nearness and alienation — proximity and insurmountability — in knowledge production and communication.

“This is me, the possible link to the new you,”

“You won’t find the footnote.”

Architectures of Disappearance