Siempre hay más

Hay que hablar de cobardía que es la manera en que se entiende aquí el aire.

Hay que hablar de miedo.

Es decir,

hay que hablar de historia.

We must speak of cowardice which is the way to understand the air here.

We must speak of fear.

That is,

we must speak of history.

Juan Carlos Bautista, “Cabezas” (“Heads”)

In the process of translating María Rivera’s poem “Los muertos,” I asked my co-conspirator Román Luján some questions about his perspectives on the context for María’s work. One of the questions I asked was which Mexican visual artists he believes are doing work that most directly engages the contexts of violence that mark Mexican geographies and social landscapes at the moment. His answer, in blue, named an artist whose work I too had thought of immediately, as I became increasingly aware of the so-called narcowar (perhaps more accurately named a war of capital or a war for social control): Teresa Margolles.

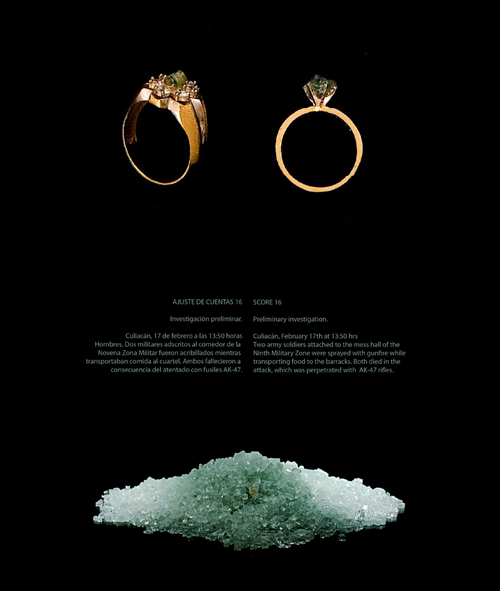

Without a doubt, the artist who uses the strongest conceptual and discursive tools to most accurately express the ramifications of the narcowar and its horrors is Teresa Margolles. She represented Mexico in the 2009 Venice Biennale with a series of conceptual pieces titled “¿De qué otra cosa podríamos hablar?” (“What Else Could We Talk About?”). These works constitute an essential document in the establishment or re-establishment of any aesthetic that might address our new culture of death—or whatever we might call it.

Margolles’ work has become a touchstone for a number of Mexican poets who seek to address the brutal violence of everyday existence in Mexico in their own work. Juan Carlos Bautista, whose epigraph begins this post (and who happens to be co-owner of one of the most fabulous queer bars in Mexico City) and Hernán Bravo Varela both cite Margolles’ work in their essays for the collection Escribir poesía en México (Bonobos Editores, 2010). There’s a fascinating and barbed exchange between art critic Avelina Lésper and Hernán Bravo Varela that centers on Margolles’ work, and the complexities of the relationship between art and brutality. A propos these complexities, just a few days ago the artist Ian Alan Paul (“experiments in politics, art and technology”) and 667 participants from 28 different countries enacted a “border haunt” to create a “border database collision” that—like Margolles’ work—uses recontextualization of information as a way to propose new modes of interpretation. The border haunt project seems particularly apt (and poignant) in relation to Menos días aquí (Fewer Days Here), a project of Nuestra Aparente Rendición (see below).

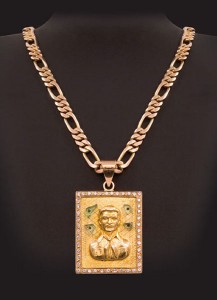

Teresa Margolles, "Score Settling 15," Jesús Malverde pendant inlaid with glass fragments from crime scene

At the other extreme are cultural manifestations that recreate, celebrate or make use of narcoparaphernalia in an uncritical, normalizing manner: narcocorridos, as well as the cults of La Santa Muerte and Jesús Malverde—both extremely popular. These are the best-known examples. However, there’s another instance that seems to me truly distressing for its level of cynicism as well as the ways it is integrated into discourses in favor of all that is narco: Movimiento Alterado, a conglomerate of norteño bands and solo singers who commercially exploit the (terrifying) idea of carteles unidos (united cartels). Movimiento Alterado is a reconfiguration of narcocorridos and reguetón. It’s an unabashed celebration of narco bling-bling—way more so than in hip-hop. We might think of Movimiento Alterado as a horrifying example of the post-narco, to borrow a phrase from Heriberto Yépez. Someone should write an essay about this “movimiento,” its various alterations.

Note: This video has been viewed more than 2,500,000 times on YouTube.

A slightly side note—or perhaps not so “side” at all: one of the people who writes most dynamically about narcocorridos is Josh Kun. When I sent Román a link to Josh’s writing, he responded:

Did you know that Los Tigres del Norte donated a huge amount of money to create The Strachwitz Frontera Collection of Mexican and Mexican American Recordings, the largest database worldwide of corridos and other forms of Mexican folk music, which is housed at UCLA? Ironies of life: Los Tigres del Norte, precursors of the narcocorrido, got really famous—and this is public knowledge—after they starting writing songs about the exploits of certain druglords; so, hypothetically, the source of that donation might be compromised. Go figure.

It’s a challenge to locate a single term in English that might capture the complexity of the phrase “movimiento alterado.” A literal translation would be “altered movement”—movement here being equally (or either) motion and a group of people working with common cause. “Alterado” does mean “altered” in any sense of the term, but is specifically used to refer to the effects of taking drugs—a synonym in English might be “high.” Any translation presents challenges, of course, but there is something especially stymieing about attempting to understand—to “translate”—the origins, parameters and topographies of the current violence in Mexico. Given the complex histories and entangled current realities of government and police corruption in Mexico, not to mention the ways that U.S. economic policies and the “war on drugs” influence the situation, it’s almost easier to comprehend (I almost wrote “trust”) the narco-traffickers, who at least are somewhat straightforward about the aims and means of what they do. How are we to comprehend the incomprehensible? And how are we to respond?

Between 2006—when President Felipe Calderón first took power and started a war against Mexican drug cartels—and the present, the political consciousness of the average Mexican changed drastically. For the first time since the Revolution of 1910, the civilian population as a whole became aware of the collapse of institutions and a general atmosphere of crisis, both political and social. Even the people who had always been ready to defend Mexico’s contradictions from foreign critics had to recognize this atmosphere of decay.

In this state of affairs, Mexican artists were confronted with many urgent questions: how to address the omnipresent terror, how to speak of the hyper-visible? For the first time since the government-sponsored massacre of students in 1968, the question arose: should artists participate actively in voicing the most immediate concerns of a decimated population? Should artists become activists? Should artists become citizens? Would it be a better choice to wait until the disaster ends to reflect upon it in retrospect and only then start the process of mourning? When did isolated stories of narcotraffic and related violence thread together into a history of narcowar? What is the language to address the continuous and senseless slaughtering of civilians? How to speak about the fear of being robbed, raped, killed, cut up in pieces?

Román asks: “Should artists become citizens?” Román speaks and writes as a Mexican citizen (that is a descriptive term, not a patriotic one) who has lived in the U.S. for the past 8 years: neither here nor there, or both here and there. When this question follows the urgent and not-at-all-abstract (given the current state of affairs) query as to whether artists should become activists, the term “citizen” takes on a newly energized charge. What are the politics and poetics of using this term? What are the implications for each of us when our “citizenship” (regardless of our documents or administrative/legal status) entails engagement with the most urgent questions facing our communities? What then is the citizen-poet?

I also asked Román if he could recommend some websites with analysis around the change in political consciousness among Mexicans. His response blew me away, and made me wish I could spend the rest of my life translating every bit of text on each of the links below (though given the not-so-speedy speed at which I work, it might be quicker for everyone reading this post to learn Spanish well enough to read these sites for themselves!).

First there is Nuestra Aparente Rendición (an incredibly thorough, compelling and awe-inspiringly brave site with the tag line “Queremos construir paz y diálogo. Por eso estamos aquí.”—“We want to build peace and dialogue. That’s why we’re here.” and a sidebar text that encourages readers: “Reproduce this information and circulate it in whatever media you can access. Send copies to your friends. Terror is based in lack of communication. Break the isolation. Feel the moral satisfaction of an act of freedom once again. Defeat Terror. Circulate this information.” When you click on “Quiénes Somos” (“Who We Are”) the following fragments appear in the banner above bios of contributors to the site: “We are victims of violence. We are victims of femicide. We are migrants. We are all our dead.” If that isn’t poetry, what the hell is?)—undoubtedly the website that has had the most impact on political consciousness inside and outside of Mexico (and it’s important to remember that Lolita Bosch is Catalonian), and which has encouraged a more participatory, and even activist approach. Additionally, I’m thinking of the recent increase in independent, irreverent citizen journalism, like Luis Cárdenas López’s podcasts Noticias Digital (remarkable in many ways, not least because the site has a poetry link—poetry here is indeed news; NAR, too, has an excellent section of poetry related to the war on drugs that includes María Rivera’s poem:). Through a use of almost rudimentary media tools, Luis (who incidentally attended a poetry workshop I led many years ago in Querétaro) comments on news he reads in the mainstream media in an entirely direct and enraged way, using a wide range of swear words to demonstrate his disillusionment—a direct correlation with Javier Sicilia’s “estamos hasta la madre”—“we’ve had it up to fucking here.”

One other figure who must be mentioned in this context: Lydia Cacho, who is arguably the most admired and respected journalist in Mexico. If there were a Mexican Pulitzer Prize she would probably be the first person to receive it. Publicly regarded as a hero, she has been able to unmask entire webs of corruption dedicated to human trafficking, drug dealing, prostitution, slavery and sexual exploitation of minors (that link, by the way, leads to Sinembargo, a great new electronic newspaper). As a result, on more than one occasion she has been kidnapped and tortured by the entrepreneurs and governors she directly accused of those crimes in her books. Currently, Cacho continues to challenge the oligarchy and ruling class through diverse press channels; for all that she is a popular symbol of bravery and hope for political change. Nothing seems to stop her in her quest in favor of a more egalitarian and democratic society in Mexico.

It is almost unimaginable for most people writing in the U.S. to contemplate writing something that might cause us to be “robbed, raped, killed, cut up in pieces”—and to be clear, when Román uses the term “robbed” here he doesn’t mean that one’s objects will be stolen, but that one’s very person could be snatched from a public place (the sidewalk, the market, a party or bar) to be held for ransom or much, much worse. Of course there are many activist communities in the U.S. where government intervention is a reality, and I imagine most people reading this post are aware that simply existing in the world as a brown person can be extremely hazardous to one’s health. At the same time, the idea that artistic or activist work could, to give just one example of thousands (tens of thousands?), result in the artist-activist having her hand chopped off (a gruesome poetic image if ever there was one) before being strangled to death is unimaginable. Or all too real. Imagine it.

Trans positions