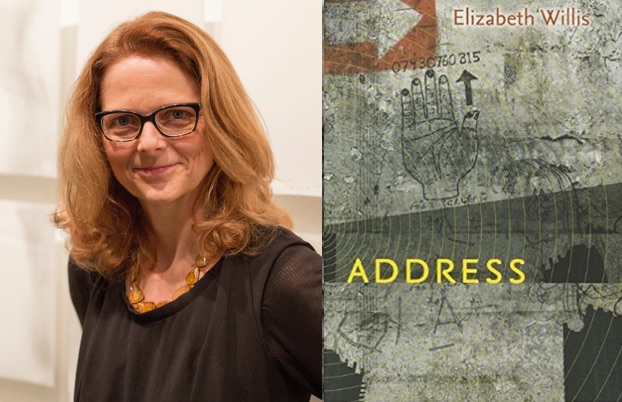

Writing puts texts in space. The procedural language of critical synthesis is inherently spatial. Thinking about connections between texts, or the bringing of texts together in an essay, simulates the positioning of objects in space. Often, writing makes texts architectural — it uses them to build, and uses the metaphorics of building. I want to use this essay to write between Elizabeth Freeman’s Time Binds and Doreen Massey’s Space, Place and Gender, texts seminal to queer temporality and to feminist geography, respectively. I want to find or put Elizabeth Willis’s 2011 collection of poems, Address, between them. When I do this, I understand that my language turns on the impulse to use the essay to imagine spatial relationships, an impulse I want to pay attention to as I think with and through Willis’s poems. I want to attend, additionally, to how the poems produce a spatial organization of time, as I read in Willis’s poems an organization of language that is bound up with that of the bodies and contexts they address.

In her discussion of how time is curated to direct bodies, Freeman uses the term “chrononormative” to refer to “the use of time to organize individual human bodies toward maximum productivity.”[1] She notes that in a chrononormative state, “institutional forces come to seem like somatic facts.”

[2] The chrononormative describes not only the curation of time, but time within particular spatial frames. Despite the fact that she identifies her project as a time project rather than a space project, Freeman says of time and space together as they relate to capital accumulation within chrononormativity, “time can be money only when it is turned into space, quantity and/or measure.”[3] If time is money when it is turned into space, time spent in the city as it is reshaped by neoliberal development is always at risk or in the process of being commodified.

I read in Willis’s poems an opportunity to use the chrononormative to think about space and time together, particularly as they are colocated within and resist a neoliberal frame. For instance, the poem “F. A. Q.” ends with the lines, “a vehicle that pays its toll / to name the day / as if it were a country.”[4] In these lines, the language of colonial projects, naming a country, gives a unit of time (the day) its spatial form. A few pages later, “Unseasonable Pastoral,” opens: “Those little hairs are really feathers / connected to the past” and closes: “A test of composition / to open the field / betrayed by nightfall’s / hourly wage.”[5] Time is hewn together by material objects (feathers). Nightfall is both temporal and spatial — a moment and a shift in physical circumstance. In these lines, Willis pivots back to the Black Mountain Poets, to Charles Olson’s “composition by field” and to Robert Duncan’s landmark 1960 collection, The Opening of the Field, to collapse the imperative to participate in innovative traditions of writing and in systems of capital accumulation.[6] The experiment of composition by field is, in the poem, itself betrayed either by the hourly wage that the poet must earn by night, or by the wage nightfall itself is paid. Hours are expensive. Innovative writing happens not outside of capital, but tethered to it, supported by the work that happens in other hours of the day. The poem’s “test of composition” is compromised by its entanglement with the chrononormative. Resisting the chrononormative (which is possible) is distinct from being exempt from or outside of it (which isn’t).

How Willis situates her poems in an experimental tradition is useful for thinking through the formal parallels and divergences between queer time and the temporal orientations of experimental poetics. The dominant temporality of many subsets of experimental poetry is a version of queer time or an antichrononormative. Language poetry, for instance, understands its experimentation with the semiotic mechanisms of language — which produces, among other results “the overwhelming of the signifier by the signified” — to be an anticapitalist gesture.[7] Pushing against the exigencies of capital also requires refusing how they organize time. Reading for queer orientations to time in experimental poetry addresses geographer Natalie Oswin’s call for engagements with queer studies that consider “more than the lives of ‘queers.’”[8] But how much more than the lives of queers is it useful to address? Are there modes of reading for queer performances of space and/or time that because of the nature of the work or the orientations of their authors detract from or compromise the identity-based origins of queer modes of reading? What is or might be the relationship between reading the queerness of bodies and the queerness of systems and texts?

While Freeman and geographer Doreen Massey both read the antinormativity of bodies and systems, the fundamental dissonance between Freeman’s writing and Massey’s is whether it is space or time that’s queer (a word that Massey, importantly, does not use, although she talks about gaps and excesses in space that appear differently for bodies based on their gender in a way that mirrors how Freeman describes queer temporality). Freeman frames her work as being focused on the project of “time rather than just space.”[9] Massey, on the other hand, situates her project against empty definitions of space and time, and against an interest in considering space without considering time, or vice versa. She’s pushing against what she identifies as the trend in postmodern geography (and the work of Fredric Jameson and Edward Soja in particular) to identify time as dynamic and space as static. In her final essay in Space, Place and Gender, “The Politics of Space/Time,” she argues, “Space is not static, nor time spaceless. Of course spatiality and temporality are different from each other but neither can be conceptualized as the absence of the other.”[10] Queer temporality, as Freeman frames it, is designed to add time to conversations about space that have already been queered. I want to pause to think about the kinds of spaces Freeman engages in her reading, and other kinds of spaces outside of these conversations that tend to behave queerly.

Queer temporality, for Freeman, when it explicitly takes up space, considers spaces that have been chiefly identity-bound, focused on (largely, though not exclusively) the gay neighborhood, bar, or performance space, rather than on the formal gaps and excesses in how urban spaces behave. Reading the chrononormative in the city requires situating queer time within the chrononormative bent of large urban spaces, but also within how those spaces cause normative time to rupture. It requires adding to queer time as a tool for managing excesses and gaps in identitarian spaces by addressing some of the largest physical excesses and gaps in the built environment in the US — vacant and deindustrialized neighborhoods, condemned houses, cleared parcels, etc. It requires addressing how these spaces are formed and at whose expense. Paying attention to these spaces also requires reading for how conceptual and physical spaces drift into and away from one another, a strength, often, of experimental poetry.

“In Strength Sweetness,” the final poem in Address, is tremendously attentive to the appearance and blur of gestural and material spaces. Its closing lines read:

in the plan / a city

in your city / its anger

in your anger / a harbor

in your harbor / a boat

in the boat / open sea[11]

This final sweep of the poem moves from plan to open sea through a series of five spatial relationships that are local to the unit of the line. These five lines share paralell structures but use them differently. In the movement from plan to city is the idea of a space and its articulation, but reconfigured. It identifies a possible future (or a time that once was the future) for the plan, worked out in the city’s built environment. Even so, it’s not like saying “there’s a man in that boy” (or something equally prescriptive) because it isn’t teleological. It doesn’t determine or foreclose, but suggests that an idea might be produced variously in the built environment. The next line makes the city possessive, “your city,” and shifts from the institutional work of planning to the somatic and affective experience of urban space. Cities are useful for thinking about the queerness of space and time for a number of reasons. Most important to the chronornormative is that cities are always institutional and somatic simultaneously, queering the clear scalar relationship between body and city as units. The somatic experience of being in a city, walking around, interacting with subways and streets and other people, is an experience of having your body mediated by the production and behavior of institutions and institutional systems.

In the poem, the relationship between plan and city is one of potential, but the link between city and anger is embeddedness. “Your city” might be a city that you know or where you live or where you’re from, or it might not be a city, but a kind of internalized human-scale network. Anger is a part of its landscape. The final three lines perch on the hinge between somatic and institutional. Anger and harbor have a relationship that’s most like anger and city, a regulated physical space containing an affect. Spatial relationships are doubly metaphorical and physical in these lines. They complicate the idea I started with — that writing is metaphorical building. They refuse the distinction that allows the city to be the physical instantiation of the plan (where the plan is a two-dimensional suggestion of spatial relationships — not all that different from the essay). The separate spatial relationships of plan and city, one representational and the other material, are made inextricable by the parallel grammatical structure of the lines and the space they take up on the page. In this essay, I have been using “spatial” to think about relationships between concepts or between units of language on the page, and “physical” or “material” to address the built environment, but as those distinctions blur in the poem, their degree of distinction becomes less apparent overall.

The poem uses “in” variously to do its spatial work. The penultimate line most exactly replicates how “in” standardly relates two objects: the harbor contains the boat. The parallel structure of the lines asks for this logic to follow in the final line, to govern the relationship between boat and open sea. Open sea is the boat’s potential, and is also a refusal of the institutional structure of the harbor: the organization and registration of many boats. But open sea is also a fiction. The poems in Address are so careful in their reading of institutional structures and the ways they organize within and among bodies. For all of their attention to institutional control, I don’t know that these poems believe in open sea. Even so, there’s also the open sea of the page, the principle of composition by field that takes the blank space below the poem’s final line and shows its openness.

The presence of the city in Willis’s final lines does not feel incidental. Cities, and even more so deindustrialized urban spaces, have been an important locus for the development of experimental poetry and its communities. The experimental poem as a located and uneven way of engaging urban space might then serve as the companion to the urban history of deindustrialization. The experimental poem is a form that has historically valued antichrononormative production and is suited to locate the making of anti-chrononormative spaces (both those forced by clearance and those made in clearance’s wake) within the larger urban systems in which they appear. How to do so without occluding the histories specific to uses of space by queer communities — how to draw out the poem as a useful model, useful in part for its resistance of completion, is one place where more work at the intersection of queer spatial studies and experimental poetics might productively occur.

1. Elizabeth Freeman, Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2010), 3.

4. Elizabeth Willis, Address (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2011), 12.

6. Charles Olson, Selected Writings of Charles Olson (New York: New Directions, 1966), 16.

7. Ron Silliman, The New Sentence (New York: ROOF Books, 1987), 16.

8. Natalie Oswin, “Critical geographies and the uses of sexuality: deconstructing queer space,” Progress in Human Geography 32, no. 1 (2008): 90.

10. Doreen Massey, Space, Place and Gender (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994), 265.

Queer Urban Poetics