Knar Gavin

Knar Gavin, our current Fellow in Poetic Practice, reviews Woodrat Flat by Albert Saijo, A Tale of Magicians Who Puffed Up Money That Lost Its Puff by Kaia Sand, and A Complex Sentence by Marjorie Welish.

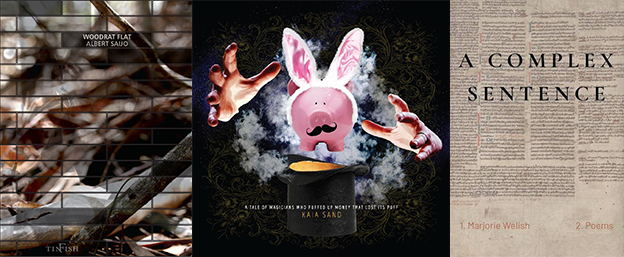

Woodrat Flat, Albert Saijo (TinFish, 2015)

Woodrat Flat is a lucid dream “WHERE FETID TURNS FRAGRANT,” and in it, Saijo takes seed and soil together to conjure the necessarily uncertain domain of radical hope: “O SEED — WHAT SHAPE WILL YOUR BEAUTY TAKE THIS YEAR.” His is a rummaging poetry, Gramscian in its embodied, militant pessimism about “EUROTECH,” the ongoing “GROTESQUE MEGADIEOFF,” “GOVT AGRIBIZ,” and the state — “EVERY STATE IS A POLICE STATE” — while also exalting, furiously, in the possibility of a “NEW POLITY” premised on “DIRECT ABSOLUTE DEMOCRACY OF NATURE.” “WE MUST SCALE DOWN,” he writes, and, in excrescent song, shit straight back into the earth: “I AM A NITROGEN FIXER TOO.”

A Tale of Magicians Who Puffed Up Money That Lost Its Puff, Kaia Sand (Tinfish, 2016)

In “Air the Fire,” an opening sequence of this Tale, Sand stages the prospect of becoming “a public person” on behalf of those living “downriver and downwind/from the malice of power.” Later, “Tiny Arctic Ice” situates the joint predicament of us “7.4 billion people breathing” within the context of an extractive, anti-life world order characterized by enclosure, carceral management, and instrumentalizing uses of human and nonhuman life. The money-puffing magician-financiers who, in “waving wands around” bits of mortgage, engineered the 2008 financial collapse, provide the backdrop for Sand’s deft depiction of this “difficult ecology of now,” which bleats for help — from the “public citizen,” the “citizen intervenor.”

A Complex Sentence, Marjorie Welish (Coffee House Press, 2021)

Across her sixth collection, Welish extends a metapoetic bid to capture and query the conditions within which meaning becomes possible. Portraiture and its defiance are present in equal measure, and the complex clarity of this text’s more aphoristic moments — for example, “To be unworthy / Of continuity is worth” — leverages fundamental aesthetic questions. What are the “implements” of thought? If winds and riverbeds alike generate “inferential / Alternative spaces,” by what materials (musical, visual, linguistic) are the “inferential / Alternative spaces” of the poem constituted? The book’s intertextual character provides a partial answer in itself, situating the stakes of repetition, depiction, sounding, and utterance always alongside those of muting and mutation, deletion and disappearance.