In late January of 2016, I phoned Carolee Schneemann and we talked for an hour or so. I had invited her to share her memories and impressions of Hannah Weiner, part of an oral history I have been compiling. What follows is a selective transcript of her remarks, with some clarifications in parentheses and interpellations in brackets. When I learned that Schneemann had passed away last week, I went back to the recording. She was generous, spirited, and finally thankful that I was working to raise awareness about Hannah Weiner’s work. I gathered from the conversation that she felt a strong kinship with Weiner. Those who have studied Weiner’s career know that its continuities are sometimes overlooked and that she dearly sought to be understood, as much as her work was in some sense a process of understanding. I think Carolee understood it. After all, she was there.

— Patrick Durgin, 3/11/19

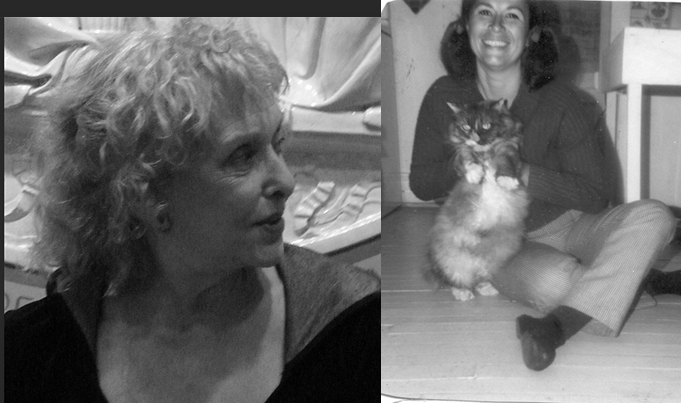

She lived around the corner from me. My loft was on 29th and hers was on 28th. She was [designing] luxury underwear and she was designing brassieres for Maidenform. And I needed Maidenform, a certain bra, for Meat Joy. Hannah might have helped me get them, because I got a whole set of what I needed. … We certainly didn’t occupy any authority (among the male poets), so because they were so approving of Hannah (Paul Blackburn, David Antin, Jerome Rothenberg), I wanted to know what she was doing. She was starting to do a lot of dream language and starting to be gestural (which connected us). We were very peripheral but I helped her with the (Code Poems). I rehearsed them with her, but it was not programmatic, it was not meticulous. … She was marginalized … a lot of people thought she was too crazy to be given proportionate regard to what they were fighting for or thinking about. … She was shy about it, insecure, we all were. She didn’t have the sort of persona that could cut through the male role of value. … Bernadette [Mayer] was also a special case, except that she was highly respected as being brilliant whereas Hannah’s work was still outside somewhere in a realm that hadn’t been absorbed at all until she was able to really enter it and sustain it. … (The embrace by Language writers changed all of that. But she didn’t come up through the university system. And the filmmakers, for example, had) meetings that defined their exclusivity. … These spiritual [voices and advisors we both had circa 1974] were highly suspect. They were against the methodical predictors, the conceptual aesthetic that was happening at the same time. So there was a certain shame or hiddenness. I couldn’t talk about this for a very long time because it would trivialize my work and make it fluffy, “fluffy girl.” … Meat Joy became hugely influential to the poets, and it was all based on dream gestures and dream energies. … [Her involvement with the American Indian Movement] was mixed, it was difficult. But they loved her. Her involvement was absolutely real. I only had a chance to visit once when I came back from London … we stayed with her in Long Island when she had that summer house [circa 1964]. I’m out there with my cat … our two older female cats. … She was always worried about money after she quit designing. She was very poor. [In the ’80s and ’90s] I used to take her out to dinner. That was a very stringent time. [Later she was] on the Lower East Side, in a kind of desperate state of disassociation. She was trying to belong to the spirits, to a poetics. That apartment was a kind of nightmare of enclosure. You had to kind of gently intrude yourself. She didn’t want to go out. And I couldn’t tell what was the creative part and what was delusional. It was very upsetting not to be able to help your friend. And to make this judgement? Very difficult. In the ’60s and ’70s she’s brilliant and she’s clear as a bell. She’s not an assertive person and with the Native American affiliation she’s smart, she’s clear, she’s determined. [Question: Testing the limit between lived experience and what is constructed and composed, you and Hannah and Bernadette were doing something brave? It’s not easy to figure out what is delusional versus what is creative.] None of us thought we were brave. That never entered our consciousness. We were doing what the work demanded. It was a funny kind of marginalization where, because it’s female, it can’t enter the fullness of the male discussion or their proprieties. So the very fact of what you say, that we were dealing with what was lived, that was, with a few exceptions, considered degraded. William Carlos Williams fulfilled that territory. But when women did it, it was still associated with diaries and embroidery and things which had less weight, less signification. And of course [Stan] Brakhage was a breakthrough for that, concentrating on lived experience. But he was not generous to contemporary women artists around him. So the men had to bolster anything that was lived experience by keeping it masculinized. Barbara Ruben is an example, and Hannah, and my work, yeah. [Question: Hannah’s invitation to the piece “Hannah Weiner at Her Job” is bright pink on light pink, with her signature and little hearts, as you describe “embroidery.” Is this ironic, I’m going to play back to you this clichéd notion of femininity?] I don’t think it was even irony. Compare it to Charlotte Moorman, who founded a community through her avant-garde festivals. She put hearts and lace and love things all over her communications. I don’t think we were as analytically clear as we can be now as to the structure of resistance and marginalization. It’s just how it was. That’s what we grew up with. The whole culture was determined by male sensibility. [Hannah’s later, clairvoyant work] is simply an exposition of living within what others continued to perceive as a taboo. For us it is not a taboo. It is where we live. Part of our dynamic is we inhabit what the culture will reframe. There’s a tendency now to blame reactionary culture, retroactively. You can’t blame it. You can criticize it. But the consciousness of analytic proportion that we have now didn’t exist then. It was just sort of stumbling around in the dark, covered in mud. Uncertainty. And that’s also what made the work so lively, magical, and confusing. [Question: The Code Poems performances I can read, but they are difficult to see. What went on when you saw or participated in them?] The closest we come now is with these wonderful translators for the deaf. It had that kind of, but it was also belonging to naval information. These are all signs and symbols that existed in a highly masculinized realm and then she inhabited them and brought them forward as a gesture of language. And it was very beautiful. She didn’t have a divine body. She wasn’t anybody’s goddess. She was a like a small, somewhat plump Jewish lady from some suburb or something. I mean, she didn’t conform to our mysterious origins. And then she brought forward this exquisite dynamic. (I did not publicly perform them but I did rehearse one.) She had me come sometimes and just watch what it was going to be and talk about phrasing and sequence. And she did really physically inhabit this language. I never saw a group version of it. The flags and the spinning wheel and the lights, they were her magic elements. It was beautiful and it had a lot of power.