The scopophilic selfie in the écriture transféminine of Juliana Huxtable's Mucous in my Pineal Gland — OR Universal croptops for all the self-cannonized saints of becoming, a screen4screen tribute

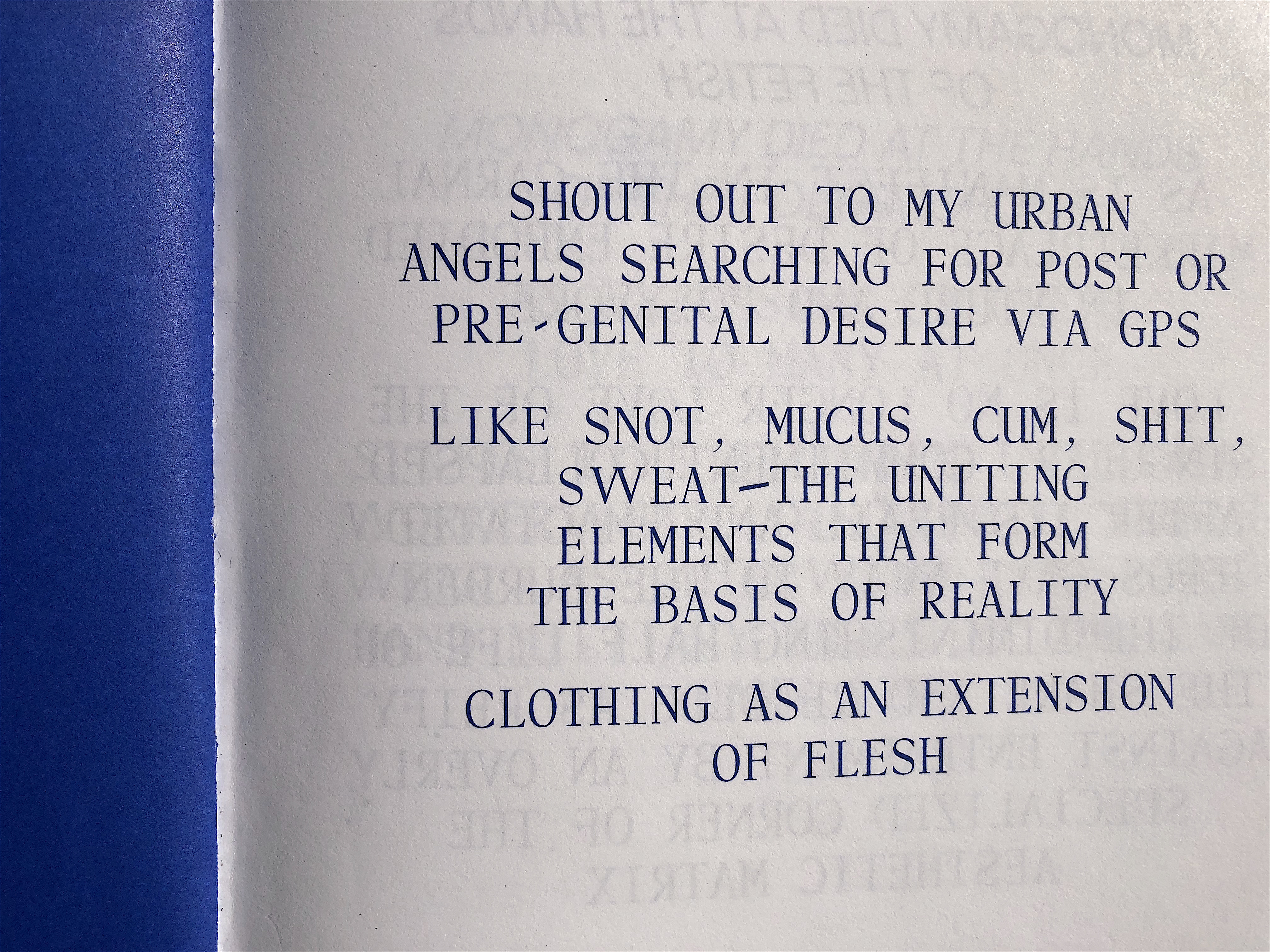

Juliana Huxtable’s new book kneels to the internet’s largesse, struggles with it like a mother. Inside this struggle: the birth of her sexuality and the body horror of femininity with its projection planes and infinite play. Also, dysphoria, blackness, fetish, queer sex. She memorializes the internet — that two-way gazing machine, the ultimate screen, constituting and constitutive of self, Self, Selfie — in loud clanking blue letters. Laura Jaramillo asserts that ASMR videos recreate a sensory and sensual materiality lost to the digital work-a-day world.[i] Similarly, Huxtable’s Mucous in my Pineal Gland permanently time stamps the ephemerality of screen text. It soothes and beautifies the eyes. It has canary yellow endpapers and section dividers of full sail blue. In blue ink and all caps, it thins the tiltingly thinning line between “send” and “publish.” Framed (or set upon a plinth) like this, Huxtable narrativizes and analyzes an entrée into the new digital sociality, layered in reappropriated codes and reused vernaculars, SO MUCH representation and infinite language. She does not line this labyrinth with golden thread, yet never lets go of a productive cynicism — critical of tech corporations and lit sharply with the traumas of race, transmisogyny, and gender normativity.

Try this: the self is outside now, held in one hundred or one thousand communication receptors — a face, a pout of lips, light on legs and pointed toes, sent / received. The self is social as ever in its isolation to work, screen, its own personal domestic economy. The domestic realm is punctured by images galore, so much social info, and sooo much language. Inasmuch as the internet is the agora, the polis, the marketplace, the café, the club, the gallery and the library — now all accessible from within the bedroom — it needs to be apprehended as an apparatus for producing the self. In ode to that maternalistic new rhetorical form, the “We-Need-To-Talk-About” essay, a thesis: we can no longer talk about the self, we need to talk about the selfie. Because the self has been ensorcelled by the screen. Because social life is in the midst of a dramatic reorganization both materially and conceptually, and the main medium of this reorganization is a gigantic representation machine which is also a gargantuan gazing machine. Because we carry subjectivity in our pockets, office equipment on our backs. I want to call it the internet, but it is more like what the internet makes possible: a complex matrix of the tech industry, the stock market, credit scoring, YouTube likes, twitter bots and of course, social media. It’s not quite the dissolution of self described by post-structuralist theory, but a little bit it is. “If the primary tool of biopolitics was the census, perhaps we can consider the paradigmatic tool of necropolitics to be the algorithm,” says Micha Cárdenas.[ii] It’s not new. It is the acuminated tip of modernism tagging or labeling an already-sorted world. On a different artist I wrote, “To imagine the self in a box, as an icon, setting preferences, adding friends, sharing links, being redirected, seeking out jobs and friends and lovers and apartments … is to continually frame and reframe binaries of ugliness and beauty, blackness and whiteness, the abject and the body, the human and the less-than-human.”[iii]

Mucous in my Pineal Gland takes on media and its constituting powers in our desires and ways of seeing and being. Someone should write the whole genealogy of this shift from self to selfie; a theory of contemporary poetics would be bereft without one. For now — from inside this digital and highly resourced glow born of office equipment and total access — an account of survival, clarity, and jouissance. Huxtable expounds upon her pleasure, writes “from the body.” Her écriture transféminine writes from a body in transition, one in a complex survival of white supremacy, from a body inextricable from a complex layering of powers, identifications, and aesthetic signs.

When I think of women and images and desire and selfies, I also think of artist Petra Courtright.

Then almost immediately, I think of the song “Meg Ryan” by Star Amarasu [please watch all the way till the end].

Inside the screen, in the bedroom, dancing with oneself, desire cut free from the (male) Artist’s hand, and also dependent on the sensus communis of (white) male desire. Race, class, and cis privilege do not emanate from selfie art, they are inherent to the medium of looking, to Western aesthetics, and are here backlit and thrown into stark relief courtesy of Apple.

Selfie art practices reverse Kant’s abnegated lust, his concept of “disinterested beauty.” They are desire, being desire. Structurally similar to feminist performance practices of the ’70s and ’80s, selfie poetics master the screen-grammar of desire with a publishing/posting rate one hundred times faster. They radiate digital glamour. Huxtable’s text is a catalog of the complexities of desire from within the screen (in every valence of that word). Says artist Hito Steyerl,

The observer has lost his stable position. There are no parallels that could converge at a single vanishing point. The sun, which is at the center of the composition, is multiplied in reflections … At the sight of the effects of colonialism and slavery, linear perspective — the central viewpoint, the position of mastery, control, and subjecthood — is abandoned and starts tumbling and tilting, taking with it the idea of space and time as systematic constructions.[iv]

More than inverting the politics of the white man’s pleasure, that which every artist who is not a white man has to deal with, Huxtable’s writing enacts desire cut loose — a force, an intensity, that power inextricable from power,[v] inextricable from resource, race, and gender dynamics, and the internet. Feminine is “one name for what we cannot grasp in established systems of ideas or articulate within the current framework in which the term ‘woman’ has meaning.”[vi] Huxtable’s work unfolds within this field of possibility. Says Hélène Cixous,

If there is a “propriety of woman,” it is paradoxically her capacity to depropriate unselfishly: body without end, without appendage, without principle “parts.” If she is a whole, it’s a whole composed of parts that are wholes, not simple partial objects but a moving, limitlessly changing ensemble, a cosmos tirelessly traversed by Eros, an immense astral space not organized around any one sun that’s any more of a star than the others.[vii]

I grappled with whether I could use écriture féminine without a responsible academic survey of the way it falls short for trans women, and it does — its metaphors of the phallus, of the umbilical cord and intrauterine space — despite its flexibility, its impulse toward becoming, its claims of anti-essentialism. Ultimately, more than that critique, I felt interested in the fecundity of Huxtable’s book. In the way that the aesthetic is always giving birth, one hundred thousand illegitimate and unholy propositions, Huxtable’s text and sex — mothered by the internet — soothes and mollifies all of us. Art, the internet, queerness, the feminine monster, “NATAL OVER&&OVERAGAIN.”

i. Laura Jaramillo, “ASMR: auratic encounters and women’s affective labor.” Jumpcut: A Review of Contemporary Media 58 (2018). “Autonomous sensory meridian response (ASMR) is a term used for an experience characterized by a static-like or tingling sensation on the skin that typically begins on the scalp and moves down the back of the neck and upper spine.” Wikipedia.

ii. Micha Cárdenas. Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility (Cambridge, MIT, 2017), 160–3.

iii. Anne Lesley Selcer, “gesture is a gender / a shining bracelet which amplifies a slim wrist.” The Capilano Review 3, no. 9 (Summer 2017): 12–13.

iv. Hito Steyerl, The Wretched of the Screen (Berlin, Sternberg Press/e-flux journal, 2012), 20–21.

v. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986).

vi. Andria Nyberg, “On Sublimity and the Excessive Object in Trans Women’s Contemporary Writing” Södertörn University, master’s thesis, 2015. Quoting Barbara Freeman, The Feminine Sublime: Gender and Excess in Women’s Fiction.

vii. Hélène Cixous, “The Laugh of the Medusa.” Signs 1, no. 4 (Summer 1975): 873–93.

The Unproductive Mouth