LISTEN TO THE SHOW

Above is Lyn Hejinian’s typescript of an untitled poem we’ve taken to calling “constant change figures.”

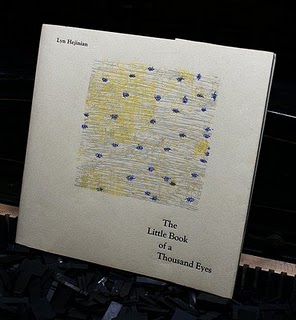

It is one poem in a series Hejinian has been writing, a project she currently calls The Book of a Thousand Eyes. If it is finished (perhaps, she tells us, in the summer of 2009?), it might consist of 1,000 poems; more likely of 310 or a few more of them (the number she had completed at the time this episode was recorded). Some poems in the series appeared in The Little Book of a Thousand Eyes, published by Smoke-Proof Press — although, please note, our poem, “constant change figures,” does not appear in that gathering. When Hejinian visited the Writers House a few years ago, she read 19 of these gorgeous little eyes, including ours. And it‘s the audio recording made during that reading that we use in our show.

It is one poem in a series Hejinian has been writing, a project she currently calls The Book of a Thousand Eyes. If it is finished (perhaps, she tells us, in the summer of 2009?), it might consist of 1,000 poems; more likely of 310 or a few more of them (the number she had completed at the time this episode was recorded). Some poems in the series appeared in The Little Book of a Thousand Eyes, published by Smoke-Proof Press — although, please note, our poem, “constant change figures,” does not appear in that gathering. When Hejinian visited the Writers House a few years ago, she read 19 of these gorgeous little eyes, including ours. And it‘s the audio recording made during that reading that we use in our show.

To what extent does our notion of nature’s picture — a picture of the many things we name “out there” — surprass the things we already know? We seem to deem memory nature’s picture. So to what extent is experience the result of our living in time, a state producing senses that are familiar and yet move us forward toward new and different effects?

So, truly, constant change figures the time we sense. “Figures” there — a transitive verb at that point — enacts things: change makes things, shapes them, renders them, gets things just so.

As you can tell from the recording, we were astonished that these words could accomplish all that thinking about words? Can you imagine writing a poem of nine triads, 27 lines in all, each line this carefully rendered — a poem that in all uses far fewer unique words than the total number of words in the poem, far fewer than conventional utterances would need to employ. Fewer, let’s say, than required by the language of philosophy telling of the same phenomena.

During our lively Hejinian PoemTalk, Tom Mandel in particular works out for us the way the shifting yet repeating triads are enacted. Bob Perelman focuses on Steinian memory (forgetting something himself along the way), Thomas Devaney on the power of turned-every-which-way phrasal variations, Al Filreis on the Steinian mode (again) and the poem as a possible critique of the ideology of experience.